We recently made the claim that societies need a bit of strife. After all, without strife, there can be no greatness.

You may or may not subscribe to this sentiment, the idea that the hottest forge creates the strongest steel, but it was nothing short of a cultural cornerstone in the earliest days of ancient Greece.

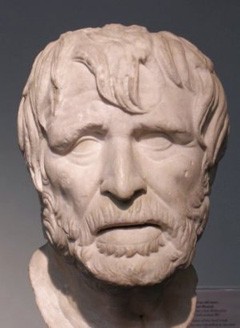

The poet, Hesiod

Take Hesiod for example.

Historians today remember the ancient poet Hesiod as a true giant of ancient Greek literature. As an epic poet, Hesiod is credited with penning The Theogony, which details the ancient Hellenic ideas of the creation of the world and establishes much of our understanding of the pantheon of Olympic gods and goddesses.

As an ancient writer, Hesiod is second only to Homer. And there are still a few things he can teach us.

Almost three thousand years ago, Hesiod wrote that there were two kinds of strife. The first strife would “foster evil war and battle.” But the other strife would spur men, and societies, to greatness.

|

Potter against potter

It’s possible that this sort of work ethic might have saved the ancient Greeks from a dire fate.

Several hundred years before Hesiod, sometime in the 14th or 13th century BC, the great and glorious Bronze Age of Greece came to an end.

The civilizations of the Minoans and the Mycenaeans, the civilizations that inspired The Iliad, were destroyed either by internal conflict or foreign armies.

The ancient remains of the palace at Knossos, a Bronze Age Minoan castle.

Ancient Greece enters a dark age. The people encounter plights that we in the modern world are unacquainted with- famine, mass migration, and an economic collapse of the known world.

A lot of strife to be sure, but with strife comes opportunity. With the collapse of traditional kings and rulers, the commoners, maybe for the first time in history, had the opportunity to toil for their own self-advancement and not just for the benefit of the ruling elite.

Here we come to Hesiod’s idea of competing craftsmen- potter against potter, minstrel against minstrel. Each is competing to get his little slice of the pie.

|

From this strife comes a revolutionary idea, it’s an idea that is still with us in the modern age. Here we find the first glowing embers of what would become known as “the cult of the individual”, the idea that a person can strive and toil to create their own fortunes, their own futures. A commoner could, for the first time, be the author of his own story.

Times might have been tough, but it was this idea, that strife can lead to greatness, that set the stage for the so-called “glory days” of ancient Greece several hundred years later.

Perhaps we don’t need less strife in our modern age. We just need the right type.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.