By Anya Leonard

“CRACK! Smash!” The sound of your favorite vase hitting the floor.

You search around for the culprit – a child, a dog, or a clumsy spouse, any of which is about to incur your wrath. Perhaps it was an earthquake, and Poseidon is to blame…

But what if, instead of looking at the broken vase as a damaged, now defunct object, you saw it as an opportunity to show its past? To display its cracks as something inherently beautiful?

Indeed, if you were a fan of the Japanese art Kintsugi, you may have even wished for the china to not so gently touch the ground. For this would give you the chance to make it even more enchanting.

Also known as Kintsukuroi (Gold repair), Kintsugi is the ancient art of fixing broken pottery with the use of gold, silver or platinum in order to highlight the fractures that are now part of the object’s history… rather than disguise it.

The results, shimmering fault lines through the earthen pot, are truly spectacular.

But appreciating mistakes and making flaws beautiful aren’t usually the first step in the history of art. More often than not, the principle aim is to create the ideal, the perfect.

This is, at least, how Ancient Greek art began.

The Archaic Period

Let’s start, for simplicity’s sake, with the archaic period, usually described as between 800 BC and 480 BC. This was the era in which the city-states, or polis, were cemented, colonies were created, and philosophy, as well as her entertaining sister, theatre, were planting their potent seeds.

Art, also, was progressing. Characteristics for which Greek Art would famously be known were already starting to shine through. This was particularly true with regards to the free standing nude statue.

Originally borrowing heavily from the Egyptian statues in pose and proportions, large scale sculptures at this time usually fell into two categories: the male Kouros, or standing youth, and the female Kore, or standing draped maiden.

These statues had the trademark ‘left-foot forward’ and ‘helmet hair’, a very stylized pattern for their tresses. They also possessed the coined ‘Archaic smile’, a somewhat condescending, if not sublime smirk, that has no correlation with the personality or situation depicted, but which, nonetheless, can be found on the majority of the statues from this time period.

A perfect example of the Kouroi of the archaic period, c. 580 BC, is Kleobis and Biton, held at the Delphi Archaeological Museum. These colossal monuments are imposing in their weight and presence, reminding viewers of the Pyramids more than the Parthenon.

While it was throughout the 6th century BC that the human representations in sculpture advanced in many ways, the desired outcome was almost always the same: to create the best, most stylized, ideal person.

Perhaps this is not so surprising when considering the purpose of their art. Archaic sculpture most often served as dedications to the gods or as grave markers. Solemn affairs, in other words. Artistic expression was less a motivation than following proper ritual and tradition.

Who knew how the Gods would have taken a dedicated statue that was frowning?

While sculpting the ideal body was attempted before the Persian war, it was arguably only perfected after the ousting of Xerxes. Of course Xerxes had nothing to do with it, he’s just the handy marker that separates what Art historians like to deem the archaic period from the Classical Period.

The Classical Period

Covering approximately 157 years, the Classical period includes the height and fall of Athens, starting with Persians and ending with the Peloponnesian war. In between these dramatic conflicts, however, Athens ruled supreme in regards to economics, politics, and importantly for this article, culture.

In fact, Athens’s indisputable position allowed for some of the most famous, influential art works ever created. See, Athens became all-powerful through her role in the so-called Delian League, which was originally a voluntary collection of Greek city-states. Athens, however, assumed the leadership spot, took over the treasury and with this newfound confiscated wealth, built the everlasting wonder that is the Acropolis.

The popular statesman Pericles simply took the Delian League’s collection to fund the greatest artists of the day and celebrate both Athens and her patron goddess, Athena. Now, with this goal at hand, you can imagine that the craftsmen, painters and sculptors depicted the perfection and power of men and gods… not their inherent flaws.

This was fifth century Athens, after all!

Nothing exemplifies this dedication to the ideal and calculated beauty than Polykleitos of Argos, who formulated a system of proportions that achieved the artistic effect of permanence, clarity, and harmony.

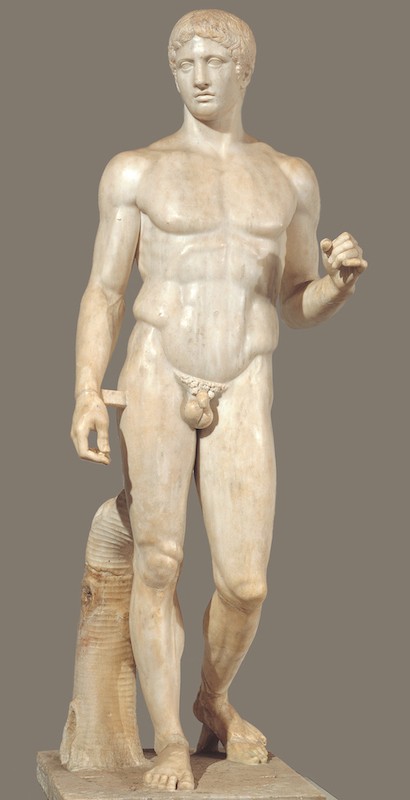

His bronze male nude, known as the Doryphoros (“Spear-carrier”), illustrates these ideals, all while casually exhibiting his famous trademark of Contrapposto, a posture in which the weight was placed on one leg.

But our Spear-carrier also reveals another interesting change in Ancient Greek Art. The persons depicted were not just the religious or the divine, but also normal folks, like charioteers or Discus-bearers. This meant a softening in positions, stances and more natural situations.

In other words, the figures were to be ideal, but also human.

And then they went a step farther. From 500 BC, Greek artists started to carve, paint and mold real, actual humans! The statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, set up in Athens to mark the overthrow of the tyranny, were said to be the first such public monuments.

This move is crucial in the shift from the perfect ideal to the wonder of flaws… because it is in the flaws that we are able to recognize the individual.

Anyone who has casually drawn a portrait of a friend will empathize with this predicament: Make it too realistic and you might offend your sitter. Make it too idealized and your obliging model won’t be recognized. We can’t imagine how portrait artists of kings and queens handled the situation!

One court sculptor, however, seems to have accomplished this task quite satisfactorily. It was Lysippos who was commissioned by none other than Alexander the Great, another great patron of the arts. Moreover, Lysippos’ busts and his creation of the ‘Heroic ruler pose’ highlight the transition between the Classical Period and the Hellenistic Period of Greek Art.

Hellenistic Period

This final era of Ancient Greek Art is usually marked by the death of that Macedonian prince, Alexander the Great. His grand empire had meant previously isolated cultures came into contact with each other, influencing styles and subjects.

Art within the region became more diverse and took contributions from the newly enveloped orbits and colonies of the empire; Greco-Buddhist art illustrates the widespread impact of this collaboration perfectly.

Meanwhile, sculpture evolved to be more and more naturalistic, both in stance and subject. Commoners were now depicted, along with women, children and animals. Wealthy families commissioned domestic scenes and everyday events for their abodes. Sculptors no longer stuck to the ideas of physical perfection, instead opting for models of all ages.

We have finally come to the beauty of flaws in Greek art.

Statues dropped their smug archaic smiles for raw emotions, exhibiting everything from love to pain and death. Solid stances were replaced with full-bodied twists and turns. Heavy folds melted to sheer fabrics revealing detailed, human forms.

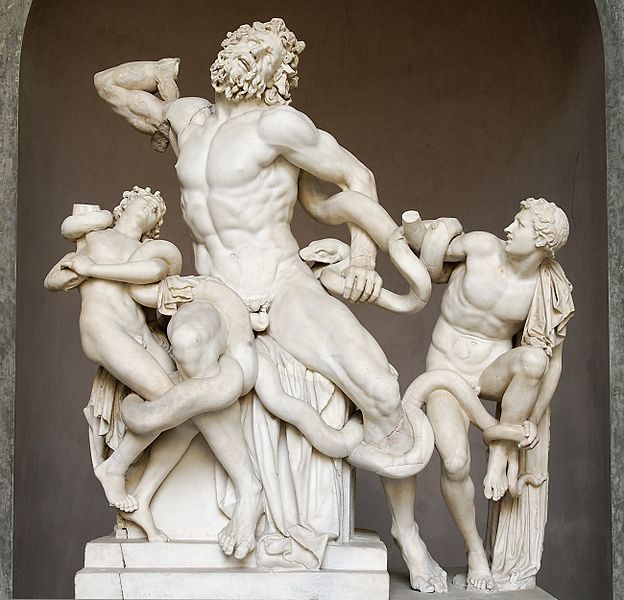

The art has left the realm of the perfect deity and reached the world of human individuality. One only has to think of the Dying Gaul or Laocoön and His Sons to see pain and suffering of mere mortals. These aren’t gods. They aren’t even ideal athletes. They are statues of a barbarian and an elderly man with his children, respectfully.

It is their turn to achieve a form of immortality as humans and show their (and our) history… flaws and all.

The artwork, and specifically the sculptures, of ancient Greece were some of the most profound, artistic statements of the human form ever to emerge from society. The dedication to detail, intricacy and exemplifying the beauty of the human body was unmatched at this time. However, like all art, it was a process of slow and deliberate evolution that created the beautiful depictions of the human body that we have all come to love, and the evolution of the man in the marble is just as intriguing as the finished product.

Not much is really known about this period of Greek art, as there is no writing found from this period to describe the artwork. The sculptures created were often very small objects like chariots and horses. Many of the pieces were placed in tombs and not intended for public display. It is possible that larger sculptures made at this time were constructed from perishable materials, like wood. This period was believed to have lasted from about 900-700 BCE.

The archaic period was believed to have lasted from about 700- 480 BCE. This era saw the first depictions of the human form. These sculptures were not the beautiful, idealized depictions that would be produced later, but instead the bodies were usually stiff and rigid. The principle sculptures at this time were given the generic term of kouros, a simplified, nude sculpture of a male youth, and kore, which was a depiction of a female youth who was normally clothed.

These statues were simplified, forward facing and lacked extensive detail. They were believed to have been influenced by the cultures of Egypt and south west Asia. The korous and kore would often be depicted smiling, which was uncommon for later sculptures. These statues would lay the ground work for later masterpieces of ancient Greece.

The classical period is thought to have begun with the sculpture known as “The Kritios Boy” in about 480 BCE. This sculpture was one of the first to depict the human form in a very realistic way. The body was sculpted to reflect accurate human proportions. The marble appears as if there are defined muscles covered by taut skin, while the sculpture itself appears to be displacing its weight on one hip. This is known as a contrapposto stance and it represented a significant innovation in the representation of human beings. While the Kritios boy is regarded as the start of the Greek classical period, it in no way encompasses the entire period.

The classical period saw the rise of brilliant artists like Polyclitus, Lysippos, Scopas,and Praxiteles. They all contributed to the innovation and realism that would come to constitute the Greek classical period. It is during this time that we see an obsessive eye for detail and, at times, an exaggeration of the human body. Many idealized statues can be seen with muscle definition and limb proportions that are unattainable by a human being. Many of the portrayals are god-like creations that would have been larger than life when compared to the average citizen of ancient Greece. Unlike the Kritios boy, which was faithful to the human form, later sculptures were heroic looking creations that captured the imagination.

the Hellenistic period would see a dramatic rise in artistic innovation in the expansive area conquered by Alexander the Great. This period is believed to have lasted from about 323-1 BCE. Although the influence of Athens, and other centers of artistic innovation during the classical period, began to decline; the influence of the eastern Mediterranean was on the rise.

While the classical period focused on idealized forms often depicted in cool, simplified stances; the Hellenistic sculptures focused heavily on sharp contrast and dramatic surroundings to create an engaging environment within the marble. The sculptors focused on the backdrop around the human subject as much as the subject itself. Figures were not always shown standing, contrapposto or otherwise. They were often seen laying down, leaning against objects, or even writhing in pain.

The Hellenistic period also saw the depiction of subjects that were less than idealized. Sculptures of humans that were old, deformed, or even dying came about during this time. In addition, it was common that the sculptures told a story.

“Laocoon and his sons” is perhaps the best example of Hellenistic style. The sculpture reflects a dramatic scene from The Iliad. Laocoon was a Trojan priest who attempted to warn his citizens about the dangers of accepting the Trojan horse. Subsequently, he, along with his sons, were devoured by a serpent, at the bidding of Athena who favored the Greeks.

Notice the powerful representation depicted. The sculpture is not a simple, standing figure, but a sharp portrayal of an event. There is believable pain displayed across the faces of the marble men. Their suffering becomes ours as their story is told to us.