Written by Stella Samaras, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom Weekly

“The poet’s grace, the singer’s fire,

Grow with his years; and I can still speak truth

With the clear ring the God’s inspire…”

Aeschylus, Chorus from Agamemnon

In 458 BCE,

the aging Aeschylus was a contender at the Dionysia. Athens, although enjoying peace between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars, was undergoing political change. Aeschylus had a word or two to sing about it. With the Dionysia on his radar he knew he had a wonderful outlet to be heard and an opportunity to persuade the masses toward empathy and reason. He also had his eye on the annual prize. He was in it to win.

The Context: Areiopagus vs Heliaia

To achieve both ends he needed to employ a thinly veiled allegory in the guise of a story from antiquity. You see, his thoughts touched upon the stripping of power from the old and well-established council of nobles, the Areiopagus, and its replacement by the more populist court of citizens, the Heliaia. The reform reduced the Areiopagus from a legislative power to just bringing down rulings on murder.

It was a touchy subject, the transference of power, the loss of honour. How to approach it? Which myth would serve his purpose? Something set during the war of the Titans, the time when the patron goddesses of the Areiopagus, the Erinyes (Furies), were born? Hmm…maybe not.

Northern Elevation of the Acropolis seen past the Areiopagus Hill before it centre left, 1888 photograph by Adolf Bötticher [Public domain]

Aeschylus, a veteran of the Persian Wars, saw the good the Areiopagos had done for Athens and wanted to remind its citizens of the virtues of this council, while reassuring the polis of its own empowered ability to mete out justice under the auspices of the goddess Athena. He wasn’t out to ruffle feathers, rather to soothe them.

Perhaps he could pitch his views in the mythical battle between Poseidon and his niece Athena? The battle was cross-generational and pertained to Athens but the scope for pathos was limited. No, the Festival called for something with more oomph.

Justice and Vengeance

Straight social commentary and pandering wouldn’t win him the prize at the Dionysia. The winning triad of plays had to provide something more, perhaps a discussion of a higher principle, one that was at the core of what the Areiopagos and Heliaia were about: an eternal principle—justice.

Should the law circumscribe behaviour by meting out justice retrospectively in acts of revenge and risk perpetuating vendetta? This was the old way, the way of the Furies whose curses and mad retribution scared Athenians into behaving. Or should justice be meted out in an Athenian court where revenge had no place and couldn’t self-perpetuate?

The Areiopagos Hill in Athens by Polychronis Lembesis [Public domain]

Aeschylus would write a cycle of three plays for the festival to hammer his point home. His story had to capture Athens’ attention: it had to establish the roots of a crime, grapple with the ethics involved, see its consequences play out, and then provide a denouement that would satisfy, cleanse, and teach. The first play would have to be tantalising, capturing their imagination and holding it through to the end of the third.

Hmm…which myth? Troy?

A Cursed House

With the Areiopagus in mind, the story had to deal with murder, but not just any murder. It had to be an act of retribution and to the minds of some, a justifiable act. Could the death of Agamemnon fit the bill? He lied to his wife, Clytemnestra, to enable him to entice her to bring their daughter Iphigenia to Aulis where the restive Greek army awaited the winds to rise. She was to be a bride for Achilles, he said.

Instead, father sacrificed daughter at the altar so his army could set sail for Troy. Ten years passed and Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus, Agamemnon’s cousin, were well prepped to avenge the murder. Once the deed was done, Orestes and Electra were compelled to avenge the death of their father with the death of his murderers.

Of course,

the house of Atreus (Agamemnon’s father) was already cursed when Atreus served his brother, Thyestes, the bodies of his children in a meal. The crime was atrocious. Until Aeschylus’ treatment of the myth, Aegisthus, the eaten boys’ younger brother, avenged them by being the one to physically plunge the sword into Agamemnon.

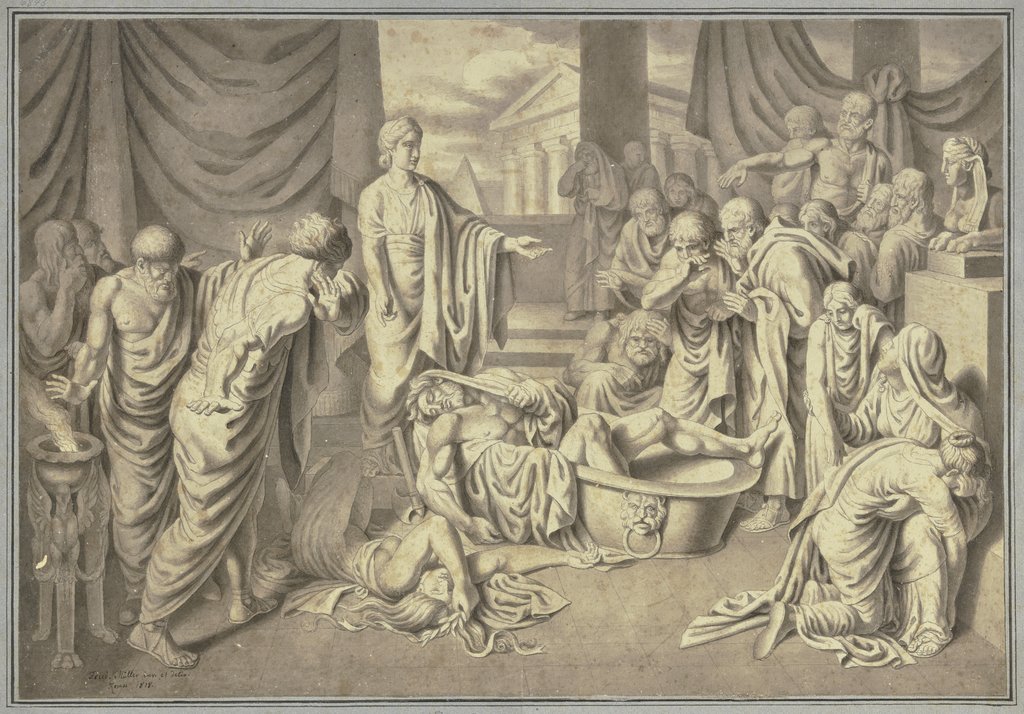

Clytemnestra wakes the sleeping Erinyes (Furies), Louvre Museum [Public domain]

However, Orestes avenging his father by killing a figure of such low esteem as Aegisthus would not elicit the pathos needed for a powerhouse production. Aegisthus was a coward, who took no part in the war but stayed at home and courted his soldier/cousin’s wife.

The Mannish-Woman and the Womanish-Man

In a stroke of genius, Aeschylus flipped the perpetrator from being a craven man to a strong woman and mother of the avenger. By placing the net and sword in Clytemnestra’s hands he heightened the dramatic tension, the pathos of the play, and highlighted the issue with calling on the Furies to provide justice.

When father killed daughter the family was cursed anew. His wife avenged their daughter as justice had to be served. The next course of justice was son killing mother. Without the intervention of the Athenian council the chain of killings would not be broken, for the justice of the Furies must needs be served regardless of the will of s/he who is called to serve it.

“If pity lights a human eye

Pity by Justice’ law must share

The sinner’s guilt, and with the sinner die.”

Having killed his mother, Orestes is Pursued by the Furies, by William-Adolphe Bouguereau

By making Clytemnestra the instrument of justice, Aeschylus faced another challenge: the audience accepting her as an equal to a man. When he refers to her in terms such as, “…Clytemnestra, in whose woman’s heart a man’s will nurses hope,” he is not making a feminist stand. Had he intended to make such a political point he would not describe Aegisthus, who he clearly has an aversion to, as:

“You woman! While he (Agamemnon) went to fight, you stayed at home;

Seduced his wife meanwhile; and then against a man

Who led an army, you could scheme this murder!”

Aeschylus, in trying to maintain a strong argument against vengeance as a form of justice, had to accord as much honour to each victim/perpetrator. He could only do this by elevating the status of Clytemnestra to be equal to a man. The choice may have perturbed some.

Fate, the Sanctity of the Guest-Host relationship and a Middling Course

Having conceived a vital plot line, Aeschylus had recourse to tragic tropes to strengthen his play. By

repeating the story of Atreus and the death of Iphigenia he reinforces the role that indelible fate plays in driving the inevitable.

The Murder of Agamemnon [Public domain]

From the outset, Aeschylus pummeled his audience with foreboding, remembering past wrongs of the family but also connecting the family curse of Atreus with Paris’ transgression, stealing away with Menelaus’ wife, Helen. Menelaus was a son of Atreus too. By reliving his grief and the consequences of the ten-year war, Aeschylus built on a sense of ill will and disharmony.

Compounding the sense of impending doom is the act of hubris Clytemnestra easily convinced Agamemnon to do – by treading on the costly tapestries she had strewn before him, he overreached his measure as a man and a king. He put the gods offside. By the time the audience is presented with his prostrate corpse, the suspense of having to wait for the inevitable has reached fever pitch.

Would all this be enough to put Aeschylus’ play on a winning path? Well, he did have more to offer.

Imagery

Did he do enough to win that year? Yes. Did he get his point across with logos, pathos, and ethos? Did his audience leave the theatre renewed by a cathartic experience? That would depend on the veracity of his actors and his music. For a victorious playwright, I’d like to imagine that they did.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.