Written by Danielle Alexander, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

When a tree falls in the forest, and nobody is around, does it make a sound? What about a musical instrument in the stars? In the evenings, can you hear the eternal whisper of its strings?

When you look up at the midnight sky, hidden amongst several larger constellations, there is the faintly twinkling Lyra—also known as the Lyre. It is located on the western edge of the Milky Way, visible in the northern hemisphere and the Tropics.

Despite its general faintness, it is easy to notice due to its brightest star, the Vega, which receives its name from ancient Indian starlore claiming this constellation is an eagle with partially opened wings. It culminates in the night sky during the evenings of early July.

The inclusion of Vega within its star cluster draws scientific interest to this constellation due to it being the first star, not including the sun, to be photographed 167 years ago. It was pulled back into the limelight when astronomers discovered a dust cloud swirling around the star, which could indicate that an unseen planet is orbiting Vega. If for us moderns this constellation is significant, what was it to the ancients…?

Ancient Greek Astronomy

There are 88 officially recognized constellations, according to the International Astronomical Union, and most of these have been documented since 150 A.D, by Ptolemy in his The Almagest. Ptolemy was drawing information from thousands of years of astronomical observations.

The Greeks absorbed astronomy and mythology from their older neighbours, the Mesopotamians, the Persians, and Egyptians, during the 6th century B.C. The Mesopotamians had all of their constellations recorded between 1300-1000 B.C., making some of the information we have today over 3,000 years old.

The oldest sources for Greek astrology can be found in the eighth century B.C. epics of Homer and Hesiod, with both mentioning two prominent constellations (Orion and the Great Bear), two-star clusters (the Pleiades and the Hyades), and two stars (Sirius and Arcturus)—but nothing more. It was not until later that Eratosthenes, a Greek academic based at the Library of Alexandria, unintentionally created the canon of the astral mythos most commonly recognized today, and undoubtedly some of his tales originated from much older skies.

For the ancients, the stars aided in navigation, and the tracking of time and constellation movements were likely noted after following the movements and phases of the moon. Not unlike modern humans, the twinkling abyss sparked their imagination, and the star clusters had legendary tales of mythic figures attached to them.

Orpheus, play your song for me

The mythos around this constellation is undeniably Greek in origin. This is because Vega may be the modern academics’ star of focus, but this constellation also houses Arcturus, one of the only two stars mentioned in the Epics of Homer and Hesiod (the other being Sirius). The constellation around the star remained unmentioned in the early works, indicating that the story emerged between the Epics (c.800-700 B.C) and Eratosthenes (276 B.C – 194 B.C).

This does not make the story straightforward. The tale has countless variations just within the works that haven’t perished through time —it really makes you wonder how much was lost. Despite all the variants, it was agreed that this constellation depicts the lyre, a seven-stringed musical instrument.

The lyre was connected, by mythology, to the Muses.

It was originally crafted by the infant Hermes out of a tortoise shell and horns from Apollo’s cattle, each of the seven strings representing the Daughters of Atlas, of which his mother was one.

“For it was Hermes who first made the tortoise a singer”

(Homeric Hymn to Hermes, c.600 B.C, 25)

Apollo, displeased and seeking vengeance, was eventually placated by Hermes after he was gifted the lyre. It was then gifted by Apollo to his son, Orpheus. He adapted the instrument to nine strings, representing each of the Muses, of which his mother Calliope was one. Clearly, there is a pattern here…

Orpheus’ skill was unprecedented, with tales telling how his songs could move and charm wild beasts or even rocks – but this is where the tale gets twisty.

One source claims that Persephone and Aphrodite selected Calliope to solve their dispute over Adonis. The seemingly logical answer, considering the situation, of ‘each of you have him for half of the year,’ proved to be an unsuitable one.

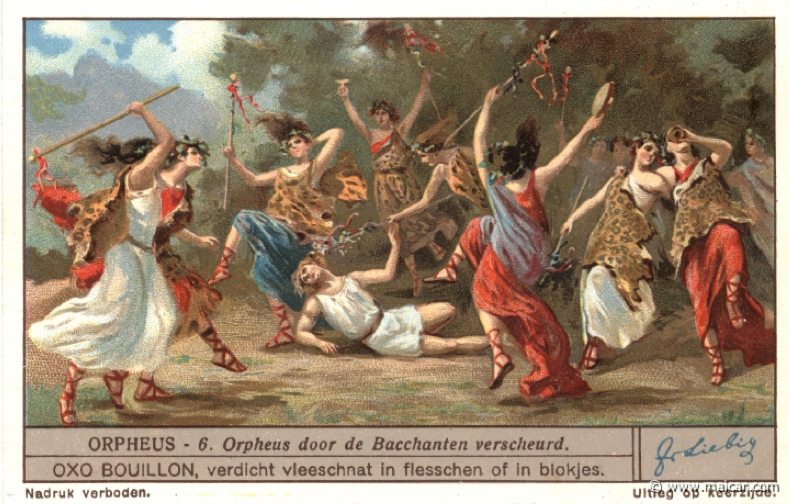

Aphrodite, enraged at Calliope’s judgement, caused all the women of Thrace to fall in love with Orpheus. In their desperate bid to have a piece of him, they tore him limb from limb. It is said that his head tumbled from a cliff to the sea and beached on the island of Lesbos. The good people performed rites and treated the head well, and so were said to be gifted by the gods at the muses’ arts.

Most sources agree that Orpheus sought out his viper-killed wife, Eurydice, from the Underworld and used his outstanding musical skills to charm the hall of Hades. The god of the Underworld allowed Eurydice to leave with Orpheus, the only stipulation being that he must not turn around to look at her – at all, not once, not even a little. True to the ‘happily never after’ character of Greek myths, the hero turned as he left the darkness of the cave to ensure his wife still walked behind him only to see her fade forever, tragically lost.

The misfortunes of Orpheus don’t end there: during his performance in the halls of Hades, he had unintentionally spurned Dionysus, forgetting to include him whilst singing praises of all the gods.

Another, more confusing, source claims that Orpheus embraced the rays of Helios, declaring him as the ‘greatest of the gods.’ His conviction to this belief saw him climb to the summit of Mt. Pangaoin— or even Mt. Olympus itself—to play his music and sing his melodies as the sun god began his charioted journey across the morning sky.

This powerful display of piety offended Dionysus. He felt completely rejected and slighted, and thus sought his revenge by unleashing the Bassarids (Meneads/Bacchae) onto Orpheus, who tore him limb from limb and scattered the pieces.

An additional variation claims that Orpheus had simply stumbled upon the secret rites of Dionysus and suffered fatally for his misfortune, while another suggests that Orpheus was the first to love another man and thus was ripped to shreds by insulted women.

In all the various tales of body dismemberment, the consistent claim is that his body parts were scattered across the land and, eventually, gathered again by the Muses to be buried at Leibethroe.

The lyre lacked a player who seemed worthy, and so the Muses requested their father, Zeus, to place the lyre in the heavens as a memorial to Orpheus. Another version claims Apollo had also appealed for the placement of the Lyre in the stars. This was agreed due to Orpheus’ brilliance with the instrument and piety to the deity. Homeric Hymns to Hermes also state that the god who crafted the lyre was the one to place it in the heavens.

It appears that while the middle of the myth may vary, the beginning and end are ultimately similar. The lyre is always created by Hermes, then gifted by Apollo to Orpheus. It always ends with Orpheus’ death, usually unpleasantly. His death leads to the lyre lacking a suitable, skilled player, and thus is immortalised in the twinkling abyss in remembrance.

All of the variations seem to be connected in different ways, such as the Underworld for Hades and Persephone, and the rejection of Dionysus in Hades and for Helios. Helios is also connected with Apollo through solar deity attributes.

Lyre, lyre, your melodies never tire

The lyre was considered a piece of art, and most Greek arts oozed mythological significance. The musical instrument, which was played similarly to a guitar and with a plectrum, was to be heard during religious rites during antiquity. However, the legendary increase from 7-9 strings contradicts archaeological evidence from 2000-300 B.C.—the strings actually decrease in number, not increase!

The tortoise is not a common zoomorphic figurine found at Greek sanctuaries and were found more in contexts relating to female deities, even when found in the Apollo sanctuary of Argos or the Hermes sanctuary of Megapolis.

There is an indication that the figurines, mostly made from terracotta but occasionally bronze too, were connected to a Bronze Age cult that used tortoises in their ritual activities, rather than the male deities of Greek myth. It seems possible that it is the ancient, arguably repressed, rites referred to in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes concerning the tortoise:

“Living you will be a charm against mischievous witchcraft, but if you die you will sing most beautifully.”

– Homeric Hymn to Hermes, c.600 B.C, 37-8

The myth of the invention of the lyre by Hermes from a tortoise shell creates an association between tortoise shell and the lyre that sees them become synonymous both in Greek and Latin literature.

The lyre connected the tortoise shell with Apollo, and the animal became sacred to the god, yet it was the lyre that was placed amongst the stars. It’s believed that this connection of Apollo and tortoise is the cause for the metamorphic transformation of the god to animal during the ‘courting’ of Dryope.

Do you hear the whisper of the strings, playing the songs of lost loves and offended gods, eternally twinkling their melodies away?

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.