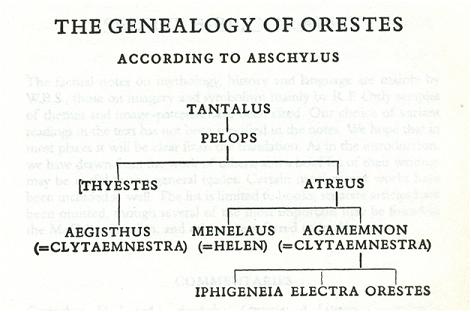

Agamemnon, was the first of a trilogy of plays (the Oresteia), performed back to back during the Great Dionysia of 458BC; it focused on two generations of ‘The Cursed House of Atreus’. Regular readers will be well-aware of the bad blood flowing through, and often out of, the members of this unfortunate dynasty.

Tantalus (grandfather of Atreus) founded this woeful household of parricide, infanticide, cannibalism, incest and hubris. His sins that doomed his descendants? Not merely stealing from the gods, but also serving them his murdered son, Pelops for dinner.

His punishment? Eternal hunger and thirst in the darkest recesses of the underworld (Tartarus) and a bloodline with filth in its veins.

Aeschylus‘ trilogy begins three generations later. By its end, the family’s seemingly perpetual cycle of hubris and nemesis, sin and vengeance, betrayal and blood will have drawn to a close.

However, there was plenty to get through before then, starting with the Agamemnon.

Agamemnon, (great-grandson of Tantalus) has returned from leading the Greeks to victory in the Trojan War and is greeted at the door by his ‘loving’ wife Clytemnestra. From this moment on we witness what has, for her, been years in the planning: the total destruction of Agamemnon.

Describing Clytemnestra as ‘loving’ is not facetious. Her strength of hate is borne from her strength of love, what we know as philos-aphilos. Clytemnestra’s hate for Agamemnon overtook/replaced her love for him when he killed their daughter Iphigenia in a religious sacrifice (without which the Greeks couldn’t have sailed to Troy).

Any lingering doubt she may have had is extinguished when she sees her husband arriving home after ten years away bearing, not flowers, tears and apologies, but a royal concubine, Cassandra.

Thus her possible motives for wanting to kill Agamemnon are:

- vengeance for her murdered daughter

- feelings for her new lover (Agamemnon’s cousin, Aegisthus)

- jealously of Cassandra

- the curse of The House of Atreus (which she frequently invokes)

- possible madness

The last reason is the only one that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Although the Chorus say to her “the red act drives the fury, within your brain”, she is, initially, remarkably cold and calculating; single and bloody-minded, but certainly not insane.

This clarity of purpose is what aids her in tricking Agamemnon into the hubristic act of entering the house on purple tapestries.

Purple was an expensive dye obtained from the murex shellfish. To walk on tapestries of this colour was an oriental excess, insulting towards the gods, not worthy of a Greek hero.

As Philip Vellacott put it: “to a Greek the essence of piety was humility, the conscious acknowledgement that the gods are greater than man, and that man’s greatness is held by their sufferance”.

Despite his initial reluctance, Clytemnestra convinces Agamemnon to commit what he knows is an impious act. She does this through a subtle reference to his sacrifice of Iphigenia:

“Might you have vowed to the gods, in danger, such an act?”

Then by appealing to his ego as the vanquisher of the King of Troy:

“Imagine Priam conqueror: what would he have done?”

And finally, brilliantly, by asking that he humour the whim of a ‘foolish’ woman:

“Yield! You are victor: give me too my victory.”

Her success in dialogue and trickery put her in the ascendancy over Agamemnon who is not only guilty in the eyes of the gods, but has also shown to his citizens that he is doomed by his own arrogance, by his god-like behaviour.

Nor is this a one-off. He has taken Cassandra as his concubine when she had previously refused the advances of the mighty Apollo. It’s almost as if Agamemnon is wearing a ‘What Would Zeus Do’ wristband which he consults before each of his foolish and despicable acts.

As Agamemnon steps foot on the tapestries, Clytemnestra lets out a “prolonged, triumphant cry”.

Agamemnon’s fate is sealed.

All that remains is the manner of his death which, although just, still manages to sicken and disturb. Clytemnestra murders her husband in his bath. Though ‘murder’ is not quite accurate, she sacrifices him, much as he had sacrificed Iphigenia:

“I gave a third and final blow, my thanks for prayers fulfilled, to Zeus.”

More disturbing still is her mania at the point of triumph:

“With cough and retch there spurted from him bloody foam in a fierce jet, and spreading, spattered me with drops of crimson rain”.

This is not a chronicle of a horror, or even victorious crowing, but feels more like Clytemnestra revelling in a disturbing and distasteful orgasm of blood: “while I exulted as the sown cornfield exults drenched with the dew of heaven when buds burst forth in Spring.”

Lust and blood-lust are intermingled to such an extent that they sully and demean the justice of vengeance. Especially in regard to the fact that she has, quite arbitrarily, decided to execute Cassandra too:

“He – as you see him; she first, like the dying swan, sang her death-song, and now lies in her lover’s clasp. Brought as a variant to the pleasure of my bed, she lends an added relish now to victory.”

This is the key question repeatedly raised in the Agamemnon: ‘What is justice’?

We can comprehend that Clytemnestra is just in killing Agamemnon, but not Cassandra. Likewise she is unjust in marrying Aegisthus, as this will disinherit her son, Orestes.

Aegisthus goes on to show a further injustice when he tries to kill the Chorus, only to be stopped by Clytemnestra:

“Stop, stop, Aegisthus, dearest! No more violence!”

Whatever the justice of the piece, there is no doubt the figure of Agamemnon lying dead in the bath; cuckolded, outsmarted, impious, naked and helpless is an entirely pathetic and unheroic end for the victorious commander of the Trojan War.

—

“Agamemnon and The Cursed House of Atreus” was written by Ben Potter

One comment

sounds a great deal like my neighbors in west virginia

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.