by Andrew Aulner, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Warfare had a profound impact on life in the ancient world. Greek theater reflected this reality, as well as the experiences of its writers; all three of the surviving Greek tragedians (Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides) were influenced in some way by war. We’ll be taking a look at each of the three in turn, beginning with Aeschylus, and seeing how warfare shaped the beginnings of theater.

Aeschylus, chronologically the first of the three great ancient Greek tragedians, fought against the invading Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC; it’s also possible he fought at the Battle of Salamis ten years later. These wartime experiences gave him an insight into the true nature of power and informed his exploration of the tension between realism and idealism in drama. There is no question that Aeschylus placed a high value upon his service in the Greek army at Marathon. His epitaph, believed to be self-composed, makes no mention of his theatrical career, yet it describes his service in the history-making battle quite prominently: “The dead Aeschylus, son of Euphorion, the Athenian / this tomb covers in wheat-bearing Gela; / the grove of Marathon can attest his famed valor, / and the long-haired Mede who knew it well”. Evidently, Aeschylus viewed himself as a veteran first and as a playwright second.

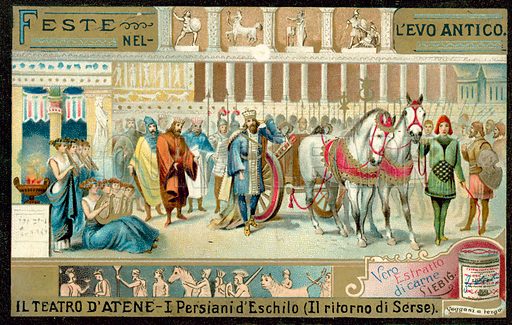

The playwright’s military service did more than give him memorable material for an epitaph, however. Power is at the center of many of Aeschylus’ plays. The Persians, a historical play that centers upon the Persian loss at the Battle of Salamis, is unique in that the playwright himself may have participated in the story’s historical events; Strauss cites Ion of Chios, a contemporary of Aeschylus’ who claims that the playwright was indeed present at Salamis.

In any case, Aeschylus uses a split chorus to depict two opposing parties, one in favor of war and the other pacifistic. This thematic division reflects Aeschylus’ observation of the civil strife in Persia following their defeat at Salamis. Such an interweaving of the two halves of a theatrical Greek chorus with the struggle between two real-life opposing political groups demonstrates that, for Aeschylus, tragedy centers around power struggles. Thanks to his firsthand wartime experience, the playwright was well-suited to depict such struggles.

Such a focus on power is not limited to the historically inspired Persians, however. The Oresteia, centered on the curse upon the House of Atreus as seen through Agamemnon, Clytemnestra, and Orestes, explores the role of a ruler, the existence of military opposition, and the legality of leadership, issues with which Aeschylus was familiar due to his military service and observations of post-Persian War politics in Athens.

Much of Agamemnon has an air of uncertainty due to the long-gone nature of the city’s sovereign, only for that void to be filled by the usurping Clytemnestra and her lover, Aesgisthus. Such usurpation means havoc for the land until Orestes avenges his father’s murder and is ultimately exonerated by a court of law. Power changes hands from a military monarch to a pair of usurpers before finally resting with a man who is declared innocent according to rule of law. This theme of the relationship between martial strength and political power is also explored in Aeschylus’s lost Theban trilogy, which was written while two leadership parties of Athens—led by Themistocles and Cimon, respectively—were in conflict regarding how to deal with Sparta following the Persian Wars. War and its aftermath provided much fuel for the fire of Aeschylus’s examination of power.

In addition to sharpening his focus on authority in the military and political spheres, his firsthand observations also gave Aeschylus the opportunity to introduce the tension between realism and idealism in his works. The playwright was not limited to his imagination when describing the realities of war. The conflicts of Aeschylus’s times enabled him to imbue his plays with lyrical descriptions of warriors, battles, and bloodshed, all of which the playwright saw for himself.

Aeschylus’s Athens idealized both military defense and conquest. Yet Aeschylus does not shy away from gritty details in favor of abstract ideals. Instead, he uses his experienced, well-informed eye for detail to draw the attention of his audience to things that they would not necessarily notice if they were to hear the story only from a civilian propagandist. He includes the other more contemptible, inglorious aspects of warfare. The readers and hearers may cheer for the glory of their country, but Aeschylus ensures that they must then confront the realities of exactly how that glory is won.

At one moment, Aeschylus can evince a trust in the greater purpose of warfare, writing that “The city of Athena will be rescued by the gods” and describing a battle cry at Marathon calling for the liberation of “the fatherland,” as well as children, women, homes, and ancestral graves. Any Greek parent would be proud to hear their children show such patriotism in defiance of the enemy. At another moment, Aeschylus can unflinchingly describe the gory slaughter of trapped Persians at Salamis: “And we [Persians] were trapped without a thing to do…In the end they rushed upon us as one, striking us, hacking like meat / Our unhappy limbs until the lives of all were utterly destroyed”. For Aeschylus, eloquent idealism and blunt realism lie within the same poetic bosom. Thus, real-life experience serves to elevate the playwright’s art.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.