Written by Barry Ferst, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Serving as a “billboard” for the faithful, images sculpted on Roman-era marble coffins offer a visualization of the Gospel of Bacchus, a graphic stone bible especially meaningful to devotees contemplating death’s doorway. Since much about the cult of Bacchus remains a mystery, a beautifully-carved frieze on a sarcophagus can go a long way to prying open some of the cult’s secrets.

By 100 C.E. the Bacchus mythos (known alternatively as Dionysus or Liber) had become standardized, i.e., made socially acceptable (the earlier Greek version could instill terror). The story begins with a double birth, first from Semele whom Jupiter has inseminated, and then from Jupiter’s thigh where the infant has been hidden from Jupiter’s jealous wife Juno. The babe is brought by Hermes to woodland creatures to be tended by them.

There, the young Bacchus is taught by a centaur and recognized as a god. As a young adult he rides in a chariot pulled by panthers or centaurs. He travels to India, which he and his troupe conquer (known as the Indian Triumph). On return, he is given an emperor’s adventus, the circus-like processional proceeded by dancing maenads. When he totters, wine-intoxicated, he is held upright by one or more of his troupe. He marries Ariadne, and he retrieves his mother Semele from the land of the dead. His friends are satyrs, pans, and centaurs.

What is known of the Bacchic rituals are the manic dances of his followers, the bacchants and maenads who play cymbals, castanets, foot clappers, bells, tambourines, and pipes. There is the sacrifice of a goat’s head, and the viewing of a snake rising from a winnowing basket. Devotees carry the thyrsus (a staff decorated with ribbons and topped with a pine cone) and hand out honey-dipped hot cakes. Ritual symbols included the laurel tree, the grape vine, and the ivy leaf. The cult was easily absorbed into Christianity.

Here, then, is a small selection from the seventy-five Bacchus sarcophagi I have personally photographed (excluding the first), each displaying a part of the Gospel of Bacchus.

THE BIRTH OF BACCHUS

This sarcophagus lid pictures the birth and early years of Bacchus. The twice-born Bacchus (first from Semele) is being taken from Jupiter’s thigh. A Homeric hymn refers to Bacchus as “insewn”:

“Be favorable, O Insewn, Inspirer of frenzied women! We singers sing of you as we begin and as we end a strain, and none forgetting you may call holy song to mind.”

THE INFANCY OF BACCHUS

This frieze on this sarcophagus depicts moments in the infancy of Bacchus. At far left the infant Bacchus stands on a small hill and holds a fennel stalk in his left hand. He looks at seated Silenus, and he is being admired by three woodland divinities. At center left Silenus, a wine skin at his feet, has a hold on a young satyr. In the right half of the frieze nymphs are tending to the care of Bacchus. They are preparing him for his bath, filling the tub with water, and bringing food.

THE RELOCATION OF INFANT BACCHUS BY SAILORS

This frieze shows five sailors on a boat accepting the infant Bacchus from a centaur. One sailor has outstretched arms ready to receive the babe, while a second gestures with upraised forefinger. At the rear of the boat a third sailor is holding the handle of the steering rudder. Given the small size of the casket, it may have been for a child, parents imaging their child being carried far away to the Isles of the Blest. The boat carries Bacchus to a distant land where Juno cannot find him.

THE RECOGNITION OF BACCHUS AS A GOD

The sarcophagus depicts the preparation for the celebration of or the Roman Bacchanalia. At left the aged Bacchus in the form of a herm statue is being raised by four young men. At far right a statue of a young Bacchus, a symbol of youthful male virility is being decorated.

THE EDUCATION OF BACCHUS

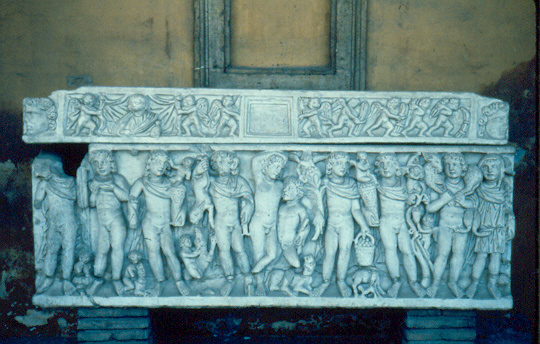

In this frieze, twenty-four figures — both human and divine — sweep across the scene. At left sits an adolescent Bacchus, listening to the music played by his teacher, the centaur Chiron. Chiron is holding a lyre in his left hand and a plectrum in his right. According to the Byzantine writer Ptolemaeus Chennus of Alexandria, “Dionysius was loved by Chiron, from whom he learned chants and dances, the bacchic rites and initiations.” Between Chiron and Bacchus is a bacchante holding a thyrsus. At far right two female devotees watch his lesson.

THE WORSHIP OF BACCHUS

This frieze depicts a processional honoring of Bacchus. A youthful Bacchus with feminine breasts and his hair in curls — an androgynous portrayal — receives devotees while slouching royally on a chair. Euripides called him “This effeminate stranger”. Silenus kneels before Bacchus.

BACCHUS DISCOVERS ARIADNE

This masterfully-carved panel of a sarcophagus shows Bacchus stepping from his chariot to gaze at the sleeping Ariadne. In this depiction, Bacchas is an old, bearded man dressed like a woman, again indicating the androgynous character of Bacchus.

ARIADNE, WIFE OF BACCHUS

By the time this sarcophagus was carved in the second half of the second century C.E., Dionysian rituals and mythos had softened. Hence this exquisite frieze, referring to when Bacchus “fell in love with Ariadne, and kidnapped her, taking her off to Lemnos where he had sex with her, and begat Thoas. Straphylos, Oinopio, and Peparethos” (Pseudo-Apollodorus), shows no kidnapping or raw sexual contact, but rather the happy wedding of Bacchus and Ariadne.

BACCHUS IN HADES

This “Bacchus in Hades” cinematic frieze creatively embellishes the story of Bacchus retrieving Semele from the Underworld.

BACCHUS TRAVELS TO INDIA

This frieze has quite the story. In 1885, a cemetery was excavated just north of Rome on the Via Saleria. During the excavation, the tomb of the family of Calpurnii Pisones was uncovered and found to contain ten large sarcophagi. One large coffin entitled the “Indian Triumph”, presents a grand procession marking Bacchus’s victory over the Indians. The scene mimics a Roman emperor’s adventus after a victory.

A BACCHUS PROCESSIONAL

This sarcophagus frieze presents a parade in which devotees would have dressed in costumes to imitate their god and his companions. Could it not also be viewed as a scene of victory over death?

RITES AND RITUALS

The frieze of this large linos sarcophagus completely covers all four sides, showing a raucous Bacchic religious ceremony and Dionysian sacrificial ritual.

VINEYARD

The scene on this lenos sarcophagus displays a rapturous gathering of men and women in a vineyard. Symbols like vineyards, vines and wine form a key part of the intoxication-driven ecstasy of the Bacchus gospel.

A GOD FOR ALL SEASONS

This frieze shows a drunken Bacchus standing with the help of a satyr at center. Called the “Seasons Sarcophagus”, Spring is represented by the two figures to Bacchus’ immediate left: one holds a rabbit and the second holds a cornucopia above which, on the figure’s shoulder, sits is a baby. With a sheaf of wheat in his left hand and basket of fruit in the other, Summer stands at Bacchus’ right. Fall is represented by the next two figures. One holds a basket of grapes in his left hand while in his right he has a grape vine. An erote (winged god representative of love) is collecting grapes from the vine. The second figure is in the “good shepherd” pose with a sheep on his shoulder. At the far left is a man in a heavy tunic and hood, symbolizing Winter. He holds a brace of geese.

FINAL REMARKS

Taken together, these sarcophagi are a veritable gospel carved in marble. Tracing the miraculous double birth, infancy, education, early and late travels of Bacchus, his love affair, marriage, rites and rituals, they point to the recognition of a “world-wide” and “for-all-seasons” divinity.

Only jubilant stories are found on sarcophagi. The sheer number of Bacchus sarcophagi is proof of the great number of adherents to the cult. Its popularity shouldn’t surprise us — like any deity, Bacchus was believed to have divine powers. He shifts attention away from problems, work and worries and towards the simple act of enjoyment — be it wine, song or passion — reminding us that we, too, have the capacity to surrender to joy.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.