By Nicole Saldarriaga

What does it take to feel sympathy for a monster? In the case of Medusa, it may not be much. Though she is considered one of the most horrifying creatures of Ancient Greek mythology (coming in at second place on Classical Wisdom Weekly’s “Top Ten Most Terrifying Monsters of Greek Mythology”) her origin story is much more complex than most people realize—in fact, most people have never heard Medusa’s origin story at all.

This may be simply because the sources available to us today differ so widely in the telling of Medusa’s story—in fact, the tale functions as a brilliant example of the way in which myths evolve over time to suit changing societal needs. Though the myth started out simple, it quickly grew and, in some ways, changed drastically—leading to a great deal of confusion when modern readers and researchers attempt to put the pieces together into an accurate representation of ancient thought.

There is, of course, some information about Medusa that never changes no matter what source you choose to look at. These are details that are incredibly well known, and seem to be passed along through a process of natural cultural osmosis. Medusa is a kind of creature called a Gorgon, she has hundreds of wild, venomous snakes for hair, and she can turn any person to stone with a single look. This concept has fascinated people for centuries, and various kinds of paintings, sculptures, cartoons, video games, and even brand labels have explored Medusa as a subject and character.

But these are the details almost everyone knows. Almost everyone knows who Medusa is, or at least what she can do. What is more interesting is how Medusa became the monster she is considered to be, and this is where the myth begins to warp and change as sources begin to disagree.

The concept of a monster such as a gorgon is an incredibly old one in Greek mythological history. We know from the creature’s appearance in the very ancient myths of Perseus and Zeus that the notion of a dreadful, snake-haired, deadly woman was born quite early. As far as the gorgon’s presence in classical literature goes, the earliest known mention of such a creature appears in Homer; and while no one can be sure of Homer’s timeline (or even his exact identity), some scholars believe that he penned his work around 1194-1184 BCE—indicating that the Ancient Greeks were talking about gorgons at a very early stage of their history.

Though Homer’s exact timeline is unknown, his mention of the gorgon places the myth among some of the oldest recorded myths of Greek history.

In the Odyssey, the gorgon is a briefly mentioned inhabitant of the underworld—one whom Persephone could apparently “sic” on anyone who angered her. It isn’t until several years later that another author gives the gorgon more of a backstory. Hesiod, in his Theogony (700 BCE), describes the gorgons as three sister-monsters born of Phorcys and Ceto, two primordial ocean deities. He calls them Stheno (“the mighty”), Euryale (“the wide wandering” or “the far springer”), and finally, Medusa (“the cunning one” or “the queen”). He also describes a key difference between Medusa and her two sisters, one that becomes extremely important later: Medusa, unlike the other two gorgons (and for reasons not explained), is fully mortal.

In these earlier myths then, it’s assumed that Medusa was born a monster—complete with snakes and stony vision. However, there is evidence that the myth changed drastically over time.

Around 8 AD, Ovid—a Roman poet celebrated for his faithful retelling of popular Greek myths—produced his famous Metamorphoses, an expansive book of myths which includes the myth of Perseus and his slaying of Medusa. In this section of the book, Ovid gives a completely different origin story for the terrifying creature.

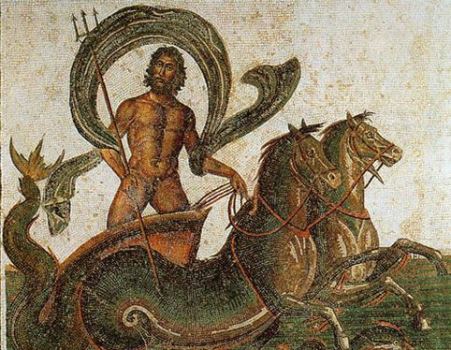

According to Ovid, Medusa was born human and grew into an excruciatingly beautiful woman. Every man who saw her face and her gorgeous, silken hair immediately asked for her hand in marriage—all but one. The sea god, Poseidon, fell for her amazing looks but instead of asking for her hand, took her virginity—raping her inside the sacred sanctuary of Athena.

Athena, as the virgin goddess, was incredibly enraged by this defilement of her temple and chose to punish Medusa for her part in the whole affair—she cursed Medusa’s beauty. According to this version of the myth, it’s at this point that Medusa’s beautiful hair becomes a tangled mass of snakes, and she is cursed with her deadly power—the ability to turn whoever looks upon her to stone.

It’s important to stress here that Medusa has no control over this ability—should anyone at all look upon her face, they’ll be instantly transformed. In essence, Athena dooms Medusa to a life of solitude, a life in which Medusa will never have the comfort of looking at another human face without destroying it—all for the crime of being raped. After years of this torture, Perseus’ sword must have come as a welcome deliverance.

Of course, this is just one version—but it has had a profound impact on the evolution of the myth and especially its propagation in modern times. These days, the most well-known (though that isn’t saying much) origin story for Medusa is closest to Ovid’s version, with only a few added details—that Medusa was a celibate priestess in the temple of Athena when she was raped, and that in addition to cursing her with a head of snakes, Athena transformed Medusa into a hideous old hag with greenish skin and fangs. But this isn’t the only version that is being passed along today.

As part of my research for this article, I read through several fan-based mythology forums, online blogs, and similar websites on which people had posted their own retellings of Medusa’s origin. The changes to the story that have taken place over time are fascinating, and are really testaments to the transformative power of imagination and word-of-mouth.

Many amateur mythology enthusiasts claim, for example, that Medusa was never raped at all. Instead, they say, she was obsessed with her own beauty and tired everyone around her by bragging about it incessantly. One day, she visited the temple of Athena with friends and spent the entire time claiming that she was more beautiful than the goddess herself, for which the goddess cursed her with an appearance so horrifying that it could turn people to stone.

This is a very interesting mixture of Ovid’s version (in which Medusa is punished for defiling Athena’s temple, though in this case the defilement is her insult to the goddess within its sacred walls) and what is possibly a misinterpretation of a line in Apollodorus’ Bibliotheca (another collection of myths dating to somewhere between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD). According to Apollodorus:

“But it is alleged by some that Medusa was beheaded for Athena’s sake; and they say that the Gorgon was fain to match herself with the goddess even in beauty” (2.4.3.).

This tells us nothing about whether Medusa was once a beautiful human woman, and clearly does not claim that Athena transformed her into a Gorgon for her arrogance, but is instead referencing her much later beheading. Still, it’s likely that this idea was passed on, and eventually led to the modern interpretations that claim Medusa’s gorgon status was punishment for her vanity.

Whether Poseidon raped Medusa, or simply took on the role of a gentle lover, it’s clear that Medusa was doomed from the moment they stepped into Athena’s temple.

Still other modern story-tellers claim that Medusa’s life was a tragic love story—that Poseidon loved her, intended to marry her (or in some versions, did marry her) and the couple made the unfortunate (and inexplicable) decision of consummating that love in Athena’s temple. In that case, Athena’s curse (while obviously worse for Medusa) is a way of punishing them both—ensuring that they would never be able to look upon each other again.

It’s more difficult to trace the potential origins of this interpretation, but it’s possible that Hesiod’s description of Medusa’s relationship to Poseidon—in which the god beds her in a romantic field of wildflowers (lines 278-79 of Theogeny) may have had something to do with it—though again, it’s only two lines of text and does not specify whether Medusa was already a “monster” when Poseidon became interested (we all know the gods weren’t exactly picky).

What’s clear from all of this is that Medusa not only lives within the realm of myth, but also within a liminal space. As long as her story is so variable, she is both monstrous and beautiful, both born to kill and cursed to a life of solitude, both arrogant and humble, both loved and horribly raped. Her story is open for us to take from it what we choose—horror and derision for a simple mythological villain, or pity and sympathy for a girl whose life was taken out of her own hands and changed very much for the worse.

I know what I’m choosing.

2 comments

Brilliant article. I especially appreciated that contemporary blogs were included in the research – hadn’t thought much about how classical myths have changed over time in response to social needs. Medusa’s backstory is also traceable along traditional religious and political ideas of sex, crime, and punishment (blame the victim – especially if she is a woman – or demonize her so that she can be discounted) and in the relatively modern attempts to whitewash sex in popular culture (it always comes back in a different form, however!). I cast my vote with Ovid’s version, although for fun I enjoy a more horror-oriented Halloween depiction. Medusa’s probable true plight is too horrifying for contemporary weak stomachs and misoginists to contemplate.

II agree with you on choosing to have sympathy for Medusa and I disagree with Lynn’s comment on using Ovid’s version, which shows how rape culture is so deely ingrained in our society. I don’t understand how a “Halloween depiction” is mlre important than eradicating rape culture from our society. This tale should actually be a case study on how unfairly females are treated, and should be used as a way to promote justice and equality for women. Men will not get away with this anymore!

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.