The Trojan War cycle is replete with anecdotes of home-wreckers and homecomings. Sure, everyone knows the sad stories of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra and Odysseus and Penelope, but there are a few more tragic tales lurking in the background. Enter Nauplius, a nasty, vengeful sailor who made quite a few soldiers’ returns from the war very, very miserable.

Nauplius

Keeping the Helen Oath

In his Epitome, often included as part of his Library, Pseudo-Apollodorus retells the story of – what else? – the Trojan War. In his version of events, when Menelaus, king of Sparta, realizes that his wife, the beauteous Helen, has absconded with the Trojan prince Paris, he calls upon his brother, High King Agamemnon, to raise an army. Agamemnon invokes an oath sworn by all the former suitors for Helen’s hand, that, if anyone should abduct or threaten Helen, all of them must come to help her husband get her back.

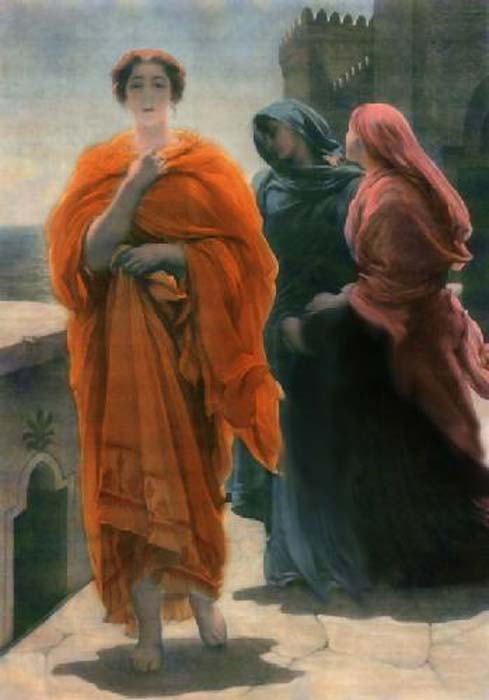

‘Helen of Troy’ (1865) by Frederic Leighton, 1st Baron Leighton.

One such suitor was Odysseus, king of Ithaca and husband of Helen’s cousin, Penelope. Although the oath had been his idea, he is not all too keen at having to leave home to make war on a foreign city for God-knows-how-long. As a result, he fakes madness when Agamemnon’s men come to pick him up. But clever Palamedes – son of the aforementioned Nauplius – realizes his ruse and proves Odysseus’s sanity by threatening the life of Odysseus’s infant son, Telemachus. To protect his little boy, Odysseus drops the act and then must join Agamemnon’s forces, since he isn’t insane. To avenge himself, Odysseus forges a letter from King Priam of Troy that makes Palamedes out to be a traitor and hides some gold in Palamedes’ tent. Agamemnon discovers the letter and orders Palamedes stoned to death for his perceived treachery.

Palamedes before Agamemnon in a 1626 painting by Rembrandt.

Treachery and Death!

Nauplius resolved to avenge himself on the Greek commanders. He did so in several ways. First, according to the late antiquity myths chronicled by Dictys Cretensis, the Greeks aimed to sail home from Troy with all their booty. But the gods chose to wreck their ships, including those of the hero Ajax of Locris. Ajax managed to survive by clinging to a log – think Titanic-style – and, seeing a light in the distance, tried to float to safety. But Nauplius had set the torch up; the land where it was situated was actually a dangerous cliff, not on a safe shore, and so when Ajax paddled towards it, he eventually was dashed on the cliffs – to his death. Other accounts state that he kindled a fire on a mountain that didn’t really contain a harbor down below, which was pretty tricky.

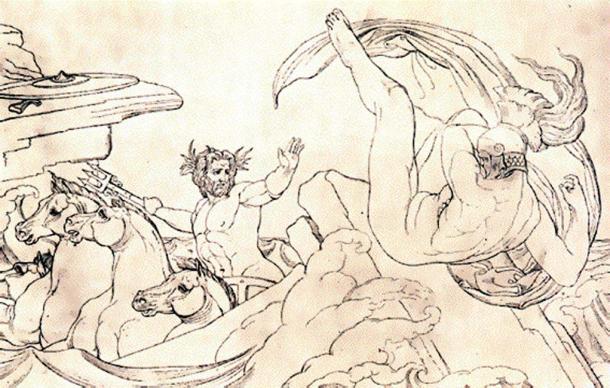

Poseidon kills Ajax the Lesser.

Oeax, brother of the late Palamedes and son of Nauplius, took up his father’s mantle. He spread malicious gossip to lots of Greek wives who were home waiting for their husbands to return to Greece. He told Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, and Aegiale, wife of the hero Diomedes (also Odysseus’s BFF), that their husbands “ were bringing back women they preferred to their wives.” Infuriated at the prospect of their spouses supplanting them with foreign slave-mistresses, Clytemnestra and Aegiale turned their hearts against their husbands. Pseudo-Apollodorus includes among the list of wives whom Nauplius corrupted the wife of Idomeneus, king of Crete.

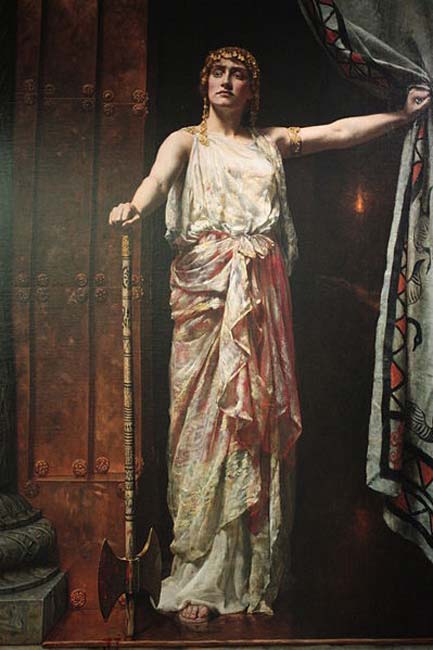

When Diomedes finally came home to his city of Argos, Aegiale barred the gates against his entry. She never let him in, and so Diomedes allegedly fled to Italy, where he founded a handful of cities. Clytemnestra, of course, had the stronger revenge. She began sleeping with Agamemnon’s cousin, Aegisthus, and plotted to kill her husband when he came home, in part for his sacrifice of their daughter, Iphigenia, prior to the war. Not only did Clytemnestra kill Agamemnon, she also bore Aegisthus a daughter bigamously (Dictys Cretensis says they were married), named Erigone. Ouch!

‘Clytemnestra’ (1882) by John Collier.

By Carly Silver, Contributing writer, Ancient Origins

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.