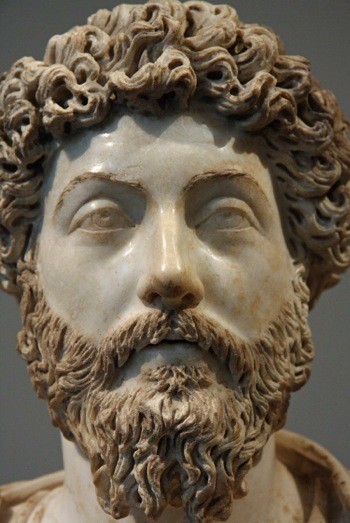

Bust of Marcus Aurelius

1. We are naturally social animals designed to help one another.

The Stoics believed that humans naturally form communities and have deep-seated social instincts. We should always bear in mind that we’re adapted to work together for mutual benefit rather than conflict and destruction. Elsewhere, in one of the most famous passages of The Meditations, Marcus tells himself to prepare each morning for the day ahead by imagining all sorts of encounters with troublesome individuals while reminding himself “Neither can I be angry with my kinsman nor hate him for we have come into being for cooperation” (2.1).

Marcus Aurelius on Horseback

2. Consider their character as a whole.

Marcus thinks we should imagine the person with whom we’re feeling angry in different situations – eating meals, sleeping, relieving themselves, having sex, etc. We should particularly bear in mind how their opinions and values shape their behavior throughout the day. When we broaden our perspective beyond the behavior that’s annoying us, we tend to dilute our feelings of anger. We also understand their actions better by placing them in a wider context, and to understand all is to forgive all.

3. Nobody does wrong willingly.

This is one of the central paradoxes of Socrates’ philosophy, which greatly influenced the Stoics. Socrates believed that no-one does wrong knowingly. It arguably follows from this that nobody does wrong willingly either. This ancient principle of moral psychology is hard for many people to accept but it’s the basis of Stoic forgiveness and empathy, and a key part of their remedy for anger. Marcus notes that everyone is offended when accused of wrongdoing. Even murderous dictators typically believe that their actions are justified, though they may seem morally egregious to everyone else.

Even murderous dictators typically believe that their actions are justified

4. Nobody is perfect, yourself included.

It’s hypocrisy to criticize others without recognizing your own imperfections – a double standard. Marcus actually said that when you notice yourself becoming angry with another person you should take it as a signal to pause and examine whether or not you’re guilty of similar, wrong-headed thoughts or actions. Acknowledging our own flaws, and bearing them in mind, can moderate the anger we feel towards others.

5. You can never be certain of other people’s motives.

Marcus had studied jurisprudence and acted as a judge in many legal disputes. He therefore knew very well how difficult it can be to know another person’s intentions. Anger, however, assumes an unwarranted certainty. Keeping an open mind, by contrast, will help weaken these feelings so that we can deal with the situation more calmly and rationally.

As the old saying goes, ‘best to walk in a mile in their shoes’

6. Remember we all will die.

The Stoics like to remind themselves that all things are transient, nothing lasts forever, including our own lives and those of the people with whom we’re angry. Before long both of you will be dead and the whole thing long forgotten. When we think about the bigger picture, it doesn’t seem worth getting very flustered about other people’s actions.

7. It’s our own judgement that upsets us.

This is perhaps the most famous doctrine of Stoic psychology. It became the philosophical inspiration for modern cognitive psychotherapy, which is based on the principle that our emotions are determined to a large extent by our underlying beliefs (cognitions). Marcus reminds himself that it’s not really the actions of others that make him feel angry but his own opinions about them, more specifically, opinions that are based upon negative value judgements. Noticing this fact alone can weaken the hold that strong emotions have on our mind but it should also encourage us to examine our beliefs and question whether there might be more healthy and constructive perspectives that we could adopt concerning the same situation.

8. Anger does us more harm than good.

This was another very common Stoic technique. Other people’s actions might harm us physically, damage our property, or our reputation. However, anger injures our own moral character. According to the Stoics, therefore, it hurts us much more deeply than another person’s actions ever could. Anger does us more harm, in other words, than the things we’re angry about. Focusing on the negative consequences of our anger can help motivate us to let it go.

Anger does us more harm than the things we’re angry about…

9. Nature gave us the virtues to deal with anger.

The Stoics frequently reminded themselves to contemplate how a wise person, such as Socrates, would deal with challenging people or events, and what strengths or virtues he might employ in specific situations. We all have inner resources that can be used to deal more constructively with difficult people, such as the capacity for patience, tolerance, empathy, and kindness. Reminding ourselves of these positive qualities and contemplating how they could be applied, can help us find an alternative to anger, and a better way of coping.

10. It’s madness to expect others to be perfect.

The Stoics were determinists who believed that the wise are seldom shocked because they view whatever happens in life as inevitable. There’s good and bad in the world. Marcus tells himself that “to expect bad people not to do bad things is madness because that is wishing for the impossible.” It’s therefore irrational to act surprised but when we’re angry we say things like “I can’t believe someone would do that!” Marcus thinks that’s naive and foolish. When someone acts in a way that’s objectionable we should tell ourselves that is to be expected from time to time. It’s just a part of life. Acting less shocked makes it easier to respond calmly and rationally to events that might otherwise make us feel enraged and offended.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.