By David Grant, Author of Unearthing the Family of Alexander the Great, the Remarkable Discovery of the Royal Tombs of Macedon

In November 1977 the ‘archaeological discovery of the century’ emerged from soil below a great tumulus at Vergina in northern Greece. Eventually four tombs and a shrine would be unearthed and dubbed the ‘cluster of Philip II’, the father of Alexander the Great. But the hopeful identification led to a backlash from scholars who questioned the archaeology.

Following thirty years of claims, counter-claims and deep divisions within the academic community, the ‘battle of the bones’ over the identities of the ‘king’ and ‘queen’ buried in Tomb II had led to nothing but a Socratic truth: ‘all I know is I know nothing for sure.’ The cremated skeletal remains from antiquity still lay silent and anonymous, but they had not been devoid of ‘nationalist’ political controversy.

In the name of ‘national’ archaeology

In 1991 Yugoslavia dissolved and out of the fallout emerged a new socialist republic to Greece’s north. Its borders fell between Albania and Bulgaria in what would have been largely ancient Paeonia and western Thrace in the time of Philip II’s predecessors. Arguably a slither of ancient ‘Upper Macedonia’, the northern cantons annexed by Philip in his expanded realm, fell into the new state. Despite the questionable geopolitics, the new Republic of Macedonia immediately adopted a twelve-point Vergina starburst of the Argead kings to adorn its national flag.

Greece saw the republic’s name and its flag as national identity theft and demanded both be changed. Street protests followed on both sides of the border and airport names were changed in line with each nation’s cause. The new regime was duly recognized by the United Nations in 1993, but only under the title ‘Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’ (‘FYROM’). Claiming ancient roots in the region under a tide of nationalism, FYROM accused its neighbor of stealing the biggest part of ‘Aegean Macedonia’ and incorporating it into northern Greece. The response from Athens was a blockade of the new Balkan player staking identity claims to the kings buried below Vergina.

The tides of politics had always tugged at the archaeology attached to Vergina and the lack of harmony between ministries responsible for antiquities resulted in a chronic lack of funding needed to make forensic progress. But the tomb debate was finally given forward momentum in 2010 when an anthropological team led by Professor Theo Antikas, with a modest 6,000-euro grant from the Aristotle University of Thessalonica, commenced a several-month task of cataloguing the Tomb II bones; their ground-breaking study would last five years.

The excavator’s proposition that Philip II and one of his wives were interred in Tomb II had always been undermined by an early ‘quick’ prognosis by a UK-based anthropologist; he had taken a ‘cursory’ look at the skeletal remains found scattered in the soil infill of looted Tomb I and his ‘tentative’ findings concluded the cist chamber housed a well-built male in the prime of his life, a young woman and a newborn baby or foetus.

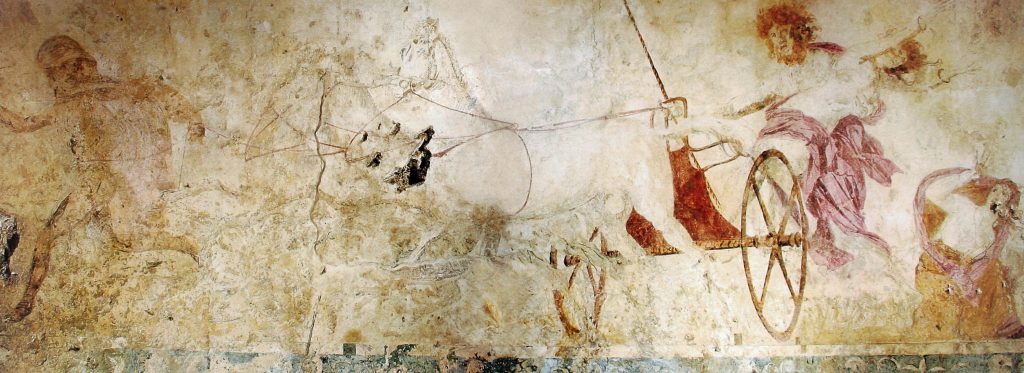

What the anthropologist unwittingly did was to give ammunition to the faction backing Philip III Arrhidaeus and Adea-Eurydice as the residents of Tomb II. By concluding that the Tomb I bones were those of a middle-aged man, a young woman and a baby, he had all but described the events surrounding the death of Philip II, whose young wife Cleopatra and her newborn were executed by his estranged wife Olympias, Alexander’s mother. If they were buried in Tomb I with its beautiful wall fresco, Arrhidaeus and Adea must have resided in Tomb II. But that was not what the anthropologist believed at all.

The Tomb I bombshell

This theory was finally put to the sword by an ‘identity-shattering’ discovery made by the Antikas team. In 2014 they came across forgotten and unanalysed skeletal remains from Tomb I in storage below the Vergina laboratory. These bones were probably consigned to thirty-five-years of obscurity in the aftermath of the ‘great’ Thessalonica earthquake of 20 June 1978 when the preservation of the unlooted Tombs II and III was the focus of attention. These additional Tomb I skeletal fragments contained the remains of at least seven individuals, not two just adults and a baby. An ugly fact had once again slayed an attractive idea.

To effectively analyse and then catalogue the Tomb II bones, the Antikas team resorted to computed tomography (CT) scanning, then each bone was catalogued with a unique number, with entries on weight, condition and morphological changes such as colour, warping or cracking. Any signs of foreign materials such as rare minerals were noted, along with comments on the conservation condition from previous handling. They next photographed each fragment from every anatomical plane, capturing over 4,000 images.

Some 350 male bones had been found in the gold chest in the main chamber. His skeleton weighed in at 2,225.8 grams, remarkably close to the mean weight, 2,283 grams, of adult male cremation remains today, a testament to the care with which the bones had been collected from the funeral pyre.

Yet, with all the modern technology at hand, on occasion there is no replacement for intense scrutiny with a simple magnifying glass. Using no more than a hand-held lens, they determined the Tomb II male suffered from a respiratory problem, a chronic condition that could have been pleurisy or tuberculosis, evidenced by the pathology they found on the inside surface of his ribs. Visible ‘wear and tear’ markers on his spine indicated he had experienced a life on horseback, while further age-related changes to the male skeleton, which had not been brought to light before, allowed the Antikas team to narrow down the estimate of the Tomb II male to 45 +/– 4 years at death.

The limping ‘Amazon’

In another ‘eureka moment’, the team identified a major shinbone fracture which had shortened the left leg of the female in Tomb II. This was a significant find as it conclusively united her with the antechamber armour, because the left shin guard or greave of a gilded pair, which had always looked rather ‘feminine’ in proportion, was 3.5 cm shorter and also narrower than the right. That, in turn, linked her to the weapons which lay beside them. Historians now had the conundrum of a limping warrioress with a precious artefact from the Scythian world.

Theo Antikas with Laura Wynn-Antikas holding the shorter greave in the Archaeological Museum of Vergina

Closer analysis of the previously unseen complete pubic bone aged her at 32 +/- 2 years years at death, and that ruled out both the earliest and the most prominent of Philip’s wives who were too old when he died, and also his final teenage bride, Cleopatra, as well as the equally young Queen Adea-Eurydice, the wife of Philip’s half-witted son Arrhidaeus. But the ‘intruder’ question remained: what was a Scythian artefact doing in a Macedonian tomb?

David Grant, a historian of the period who has collaborated with the Antikas team for the past three years, doesn’t see the need for a ‘foreign’ identity, despite the Scythian-styled quiver: ‘the Scythians were not renowned as metalsmiths; the exquisite jewellery we find in their graves is the workmanship of overseas Greeks, likely from the Bosporus Kingdom, close to today’s Crimea in the northern Black Sea.’

But there was also a thriving metalworking industry in Macedon itself, where weapons and armour were fashioned for Philip II. The possible domestic manufacture of what could have included ornate goods for Scythian warlords, with whom diplomatic links were being forged in the era of Philip, means the ‘Amazon’ of Vergina could have been born rather closer to home’. Grant has now proposed a new identity for the Tomb II warrioress.

In doing so Grant highlights the prominence of politically empowered women in Macedon during and after the reign of Philip and his son. There was even a pivotal conflict termed the ‘First War of Women’ between Alexander’s Epirote mother Olympias and Arrhidaeus’ young martially trained wife, the part-Illyrian Adea-Eurydice, in the scramble for power in the post-Alexander years. The now-preeminent nation into which Philip had ‘imported’ foreign brides’ was not short of pugnacious women prepared to ‘weaponise’ themselves!

Orphic mask and burial rituals

The Antikas team comprised both anthropologists and material scientists. Their additional microscopic finds, including textile stains, composite material fragments and melted metals on the cremated skeletons, hinted at ancient burial rituals, a death mask and the profound belief in the afterlife as part of the funerary rites.

The rare white mineral huntite was discovered with Tyrian Purple on the bones of the Tomb II male, bound with egg-white in layers. This clearly man-made composite material which evoked a vivid image of an unknown Orphic funeral rite involving a white death mask of the type found at Mycenae as well as other Bronze-Age and Archaic-Period graves. Melted gold on the upper vertebrae suggested the king was initially wearing his gold wreath as flames licked the funeral pyre, because the incomplete oak-leave-shaped wreath found inside the tomb showed similar signs of intense heat.

There may even be fragments of a fireproofing asbestos shroud which wrapped the cremated male, just as the Roman naturalist Pliny claimed was the practice of ancient Greek kings to separate the bones from the rest of the pyre debris. What had also become clear in the study was that the bones of the ‘king’ and ‘queen’ were subject to distinctly different pyre conditions, supporting the idea that they were cremated at different times.

‘Final-solution’ forensics

The Antikas team’s finds were published in an academic journal 2015. Although hampered by continued underfunding and a seeming lack of support from those fearing unwanted results, they continued to push for ‘next-generation’ forensics: DNA testing, radiocarbon dating, and stable isotope analysis on the Tomb II and Tomb III bones.

Permission was denied in 2016, Grant reveals. Instead the scientists were only allowed to test the scattered bones found in looted ‘Tomb I’ and a nearby ‘hidden’ burial pit found nearby the ancient city marketplace, but no formal funding was provided to facilitate the study.

Although these bones lay exposed in soil and water for over 2,000 years, dating and DNA results were successfully extracted, disproving yet more of the identity theories. Moreover, controversial Tomb I leg bones, which had been introduced into the ‘battle of the bones’ as supposed evidenced the terrible a knee wound Philip may have suffered in Thrace, appeared under scrutiny to be ‘intruders’ from a completely different tomb. The results have not been previously published and they will amaze everyone, says Grant.

Gold wreath found sitting in muddy water with the cremated bones of an adolescent male near the ancient marketplace of Aegae.

What the results incontestably tell us is that the great earthen tumulus at ancient Aegae was bitten into by looters on more than one occasion, when the exposed Tomb I became a dumping ground for the dead.

Now Grant’s new book is revealing all, the pressure will certainly be on the Greek Ministry of Culture to take a new progressive stance on permitting the outstanding forensics on the ‘royal’ bones from the unlooted tombs. With the possible identities greatly narrowed down by the Antikas-team study, new DNA, radio carbon dating and stable isotope analysis of the ‘king’, ‘queen’ and ‘prince’ may solve the puzzle once and for all.

In Grant’s opinion, ‘the “bones” are the real magic of Vergina’ where a steady stream of tourist buses arrives every day to visit the ruins and subterranean museum which houses the still-visible tombs and gold and silver artefacts. His book is set to raise more than eyebrows as it unveils the untold backstory of the royal tombs of Macedon.

Unearthing the Family of Alexander the Great, the Remarkable Discovery of the Royal Tombs of Macedon by David Grant is available from Amazon and all major online book retailers.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.