By David Grant, Guest Author, Classical Wisdom

On

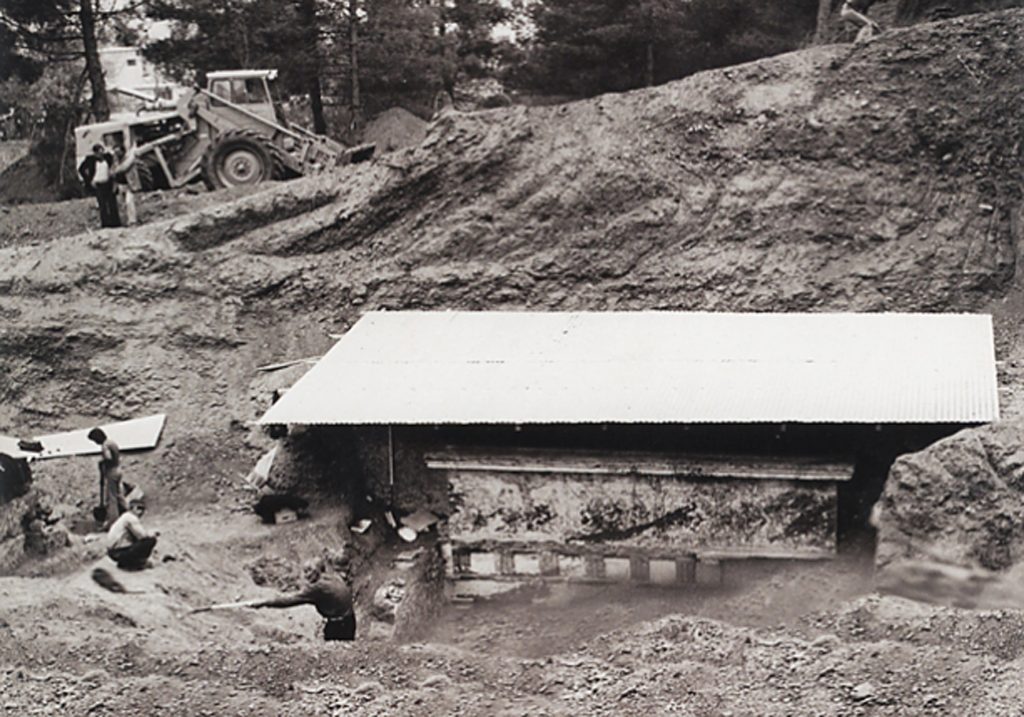

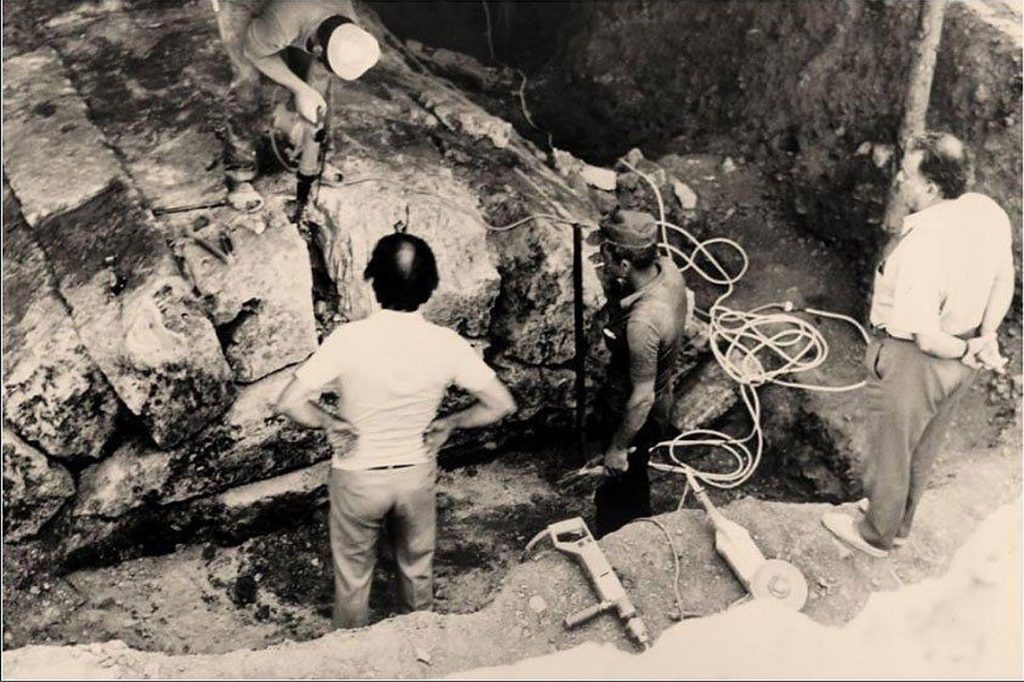

November 8, 1977, ‘Archangel’s Day’ in Greece, an excavation team led by Professor Manolis Andronikos was roped down into the eerie gloom of a rare Macedonian-styled tomb at Vergina in northern Greece. Dignitaries, police, priests and politicians watched on as the first shafts of light in 2,300 years penetrated its interior.

Tomb II emerging from the earth

The removal of the keystone to enter Tomb II

The artefacts within were broadly dated to the mid-to-late fourth century BC (350s to 310 BC) and stylistically corroborated by pottery, metal artefacts and the evolving tomb design itself. Intriguingly, these years spanned the reigns of Philip II and

his son Alexander the Great. The unique ‘Vergina Sun’ or ‘Star’ design of the royal clan of Macedon was embossed on the lids of the two gold chests holding the cremated bones.

The gold chest of ‘larnax’ holding the male bones in the main chamber of Tomb II, with the royal ‘Vergina Sun’ or ‘Star’ symbol

In October 336 BC, statues of the twelve Olympian Gods were paraded through Aegae, the ancient capital of Macedon. Following them was a thirteenth, a statue of King Philip II who was deifying himself in front of the Greek world. Moments later Philip was stabbed to death; it was a world-shaking event that heralded in the reign of his son, Alexander the Great. Equally driven by his heroic lineage, Alexander conquered the Persian Empire in eleven years but died mysteriously in Babylon. Either side of his reign, his father and family were buried at Aegae with lavish ceremonies, but the location of the city was lost.

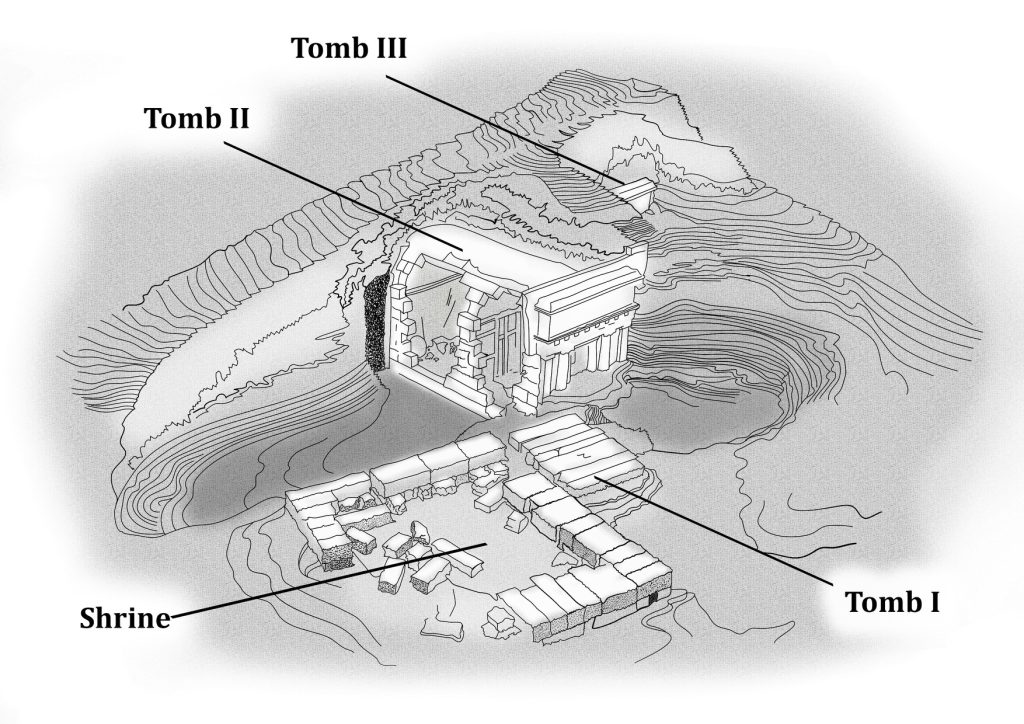

Andronikos proposed Tomb II could be nothing but the resting pace of King Philip II of Macedon who was assassinated at Aegae, the burial ground of its kings, while some commentators believed the adolescent in Tomb III was Alexander’s murdered teenage son. Along with an earlier looted cist tomb and the adjacent ruins of a shrine, the grouping soon became known as the ‘cluster of Philip II’. In November 1977, the exalted excavator had hastily convened a press conference and informed the Prime Minister of Greece, oblivious to the political backlash his identity claim would encounter in the decades that followed.

A model of the shrine and tombs under the Great Tumulus at Vergina

Why the Tombs Vanished from History

The political capital of Macedon was moved from Aegae to Pella a century before Philip’s reign. Alexander died in Babylon in 323 BC, his thirty-third year, and his embalmed corpse was taken to Egypt where it remained well into the Roman Principate before vanishing. The failure to bury him in the traditional cemetery at Aegae invoked an ancient prophesy that the nation was destined to fall. The infighting of Alexander’s generals, who proclaimed themselves kings across the newly-conquered Graeco-Persian world, saw the empire fragment into Successor Kingdoms and there followed generations of internecine war when Macedon was itself divided. The prophesy was fulfilled.

In the 270s BC, two generations later, invading Gallic Celts ransacked the old cemetery at Aegae. When the danger had passed, the still-unlooted royal tombs were buried under a great earthen to protect them from further looting by an unnamed monarch.

A century on, when Rome defeated Macedon at the battle of Pydna in 168 BC, both Aegae and Pella were partially destroyed. A landslide covered much of what remained at Aegae in the first century AD, and as Rome’s influence expanded East, the importance of the cities diminished. When Rome’s empire was finally overrun, the name of the fallen-stone city survived in oral legend only. What was likely an earthquake caused the collapse of the top of the earthen tumulus and shattered doors in the tombs below, but the sturdy stone structure remained hidden under the occupied landscape for the next two thousand years.

Rediscovering the Ancient Kingdom

Modern excavations started in occupied Greece in 1855 in what was still part of the Ottoman Empire, but nothing more than ransacked tombs were found. However, the intriguing scale of the stone foundations suggested a substantial city once stood in the hills overlooking the Thermaic Gulf southwest of Thessalonica, the heartland of ancient Macedon.

Malarial marshlands hampered excavations and Greek refugees who had been resettled there from Turkish Anatolia after the Graeco-Turkish War knew nothing of its history. They used the ancient fallen stones from the anonymous ruins to build houses at the modern village of Vergina, named after a queen of legend.

In 1968 English historian Nicholas Hammond proposed the ‘heretical’ idea that the ruins at Vergina actually sat on the site of ancient Aegae. Few credited his theory; the belief prevailed that this was either the lost city of Valla, or a summer palace of unknown royalty.

In 1976 Professor Andronikos and team finally excavated the ancient necropolis where graves had been overturned and tombstones smashed in antiquity. This correlated strongly with the ancient texts claiming Celts had plundered the cemetery at Aegae; the burial ground of the nation’s kings had finally been found.

But an ‘unfortunate symmetry’ obscured the background to the double burial in Tomb II, says London-based historian David Grant who collaborated with the scientists studying the skeletal remains. This led to a ‘battle of the bones’ among historians, causing a rift which divided the academic community ‘obsessed’ on proving their identities.

The Tomb II occupants could either be Alexander’s father Philip II and his final teenage wife Cleopatra, as Andronikos believed, or Philip’s half-witted son Arrhidaeus who was executed twenty years later when of similar age with an equally young bride. Questions of ritual or forced suicide raised their head, because kings and queens rarely died together.

Philip II was a national hero who befitted such a tomb and he had seven wives we know of. But Grant’s research points out the elephant in the room: none of the ancient sources mention any women being buried with Philip at Aegae. What superficially appears to be a two-phase construction of Tomb II, plus the different cremation conditions the female bones underwent, suggest she was buried later than the male in the still-empty or incomplete second chamber.

On the other hand, Arrhidaeus and his young bride Adea-Eurydice were executed together by Alexander’s mother Olympias when she regained political control of the state capital. This ‘double assassination’ explains the ‘double burial’ given to them after Olympias was herself executed, the opposing ‘team’ of scholars argued.

When Alexander the Great died in Babylon in 323 BC, his royal regalia, including his cloak, sceptre and ceremonial weapons were passed to the newly crowned ‘King Philip III Arrhidaeus’ and escorted with him and Adea-Eurydice back to Macedon. So, they further proposed, the artefacts in Tomb II could be the very weapons of Alexander, explaining the grandeur buried with the half-wit king.

Why Philip and Alexander remain Greek national treasures

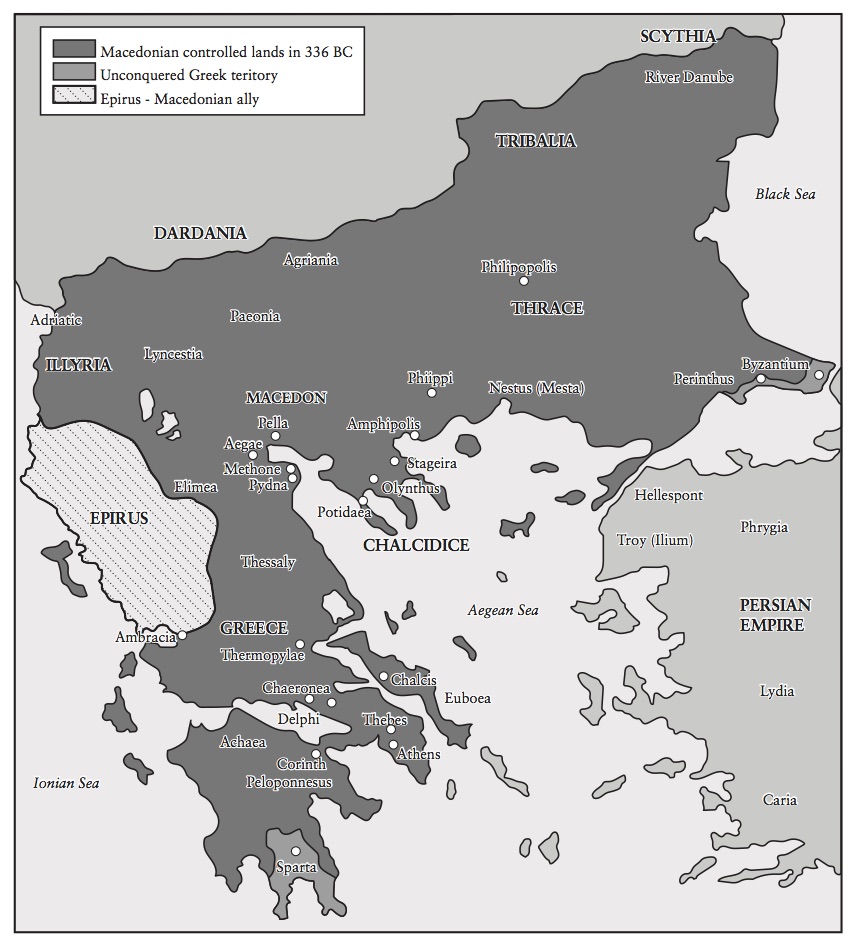

Philip II was the twenty-fourth monarch of a royal line stretching back, court propaganda claimed, to Olympic Gods and heroes. He was the first king to unite ancient Macedon and treble the land mass under its control into the first ‘European Empire’. His military reforms and statecraft brought Greece to its knees, enabling his son, Alexander the Great, to conquer the Persian Empire. Philip was a cultured cunning diplomat whose polygamous court hosted seven wives.

Lands controlled by Macedon at the end of Philip’s reign in 336 BC

Modern Greece reveres Philip and Alexander as national treasures. Yet this enduring adoration has always been something of a paradox: Philip and his son smashed Greek power at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, thereby ending one-hundred-and-seventy years of democracy that would disappear from Athens for the next two millennia. It also marked the end of the ‘Classical Age’ of Greece. Moreover, contemporary Athenian orators like Demosthenes proclaimed that the ‘Macedonians did not even make good slaves.’ However, the reigns of Philip and Alexander paved the way for the Hellenistic Era which spread Hellenic culture throughout the Graeco-Persian world; this is the true achievement still embraced today.

The Mystery of the Scythian ‘Amazon’

At the centre of the Vergina tomb debate lay an ‘intruder’ weapon of great controversy:

a gold-plated Scythian bow-and-arrow quiver like those carried by Scythian archers; the Tomb II female appears to have been a renowned ‘warrioress’. Grave digs in Russia and Ukraine have proven the existence of female warriors in this period, and so the excavator postulated that the Tomb II woman must have had ‘Amazonian leanings’. Here Andronikos was referring to the matriarchal race who featured prominently in ancient Greek legend and whose latter-day descendants were said to be Scythian female mounted archers.

The gold quiver and greaves of the female in Tomb II stacked against the chamber-dividing door.

Others were more skeptical of the connection. ‘Weapons were for men what jewels were for women,’ reads a plaque in the subterranean Vergina Museum. Because of this arguably archaeological “gender bias’, many commentators believed that the antechamber weapons belonged to the man next door, as their upright position against the dividing door might indicate. The tomb conundrum remained unsolved.

One early hypothesis of the identity of the Tomb II female favoured a presumed daughter of King Atheas of the Danubian Scythians who at one stage planned an alliance with the Macedonian king by adopting Philip as his heir, despite having a son. The once-friendly relationship with Atheas broke down, but scholars conjectured that a daughter, given freely or taken with the 20,000 captive women in the wake of the briefly-enjoyed Macedonian victory, could then have become Philip’s concubine or possibly his seventh wife of what would then be eight in total.

A female Scythian archer with hip-slung bow-and-arrow quiver from an Attica plate dated 520-500 BC.

Elegant as the hypothesis sounds, no daughter is ever mentioned in the ancient texts. Adopting Philip was rather a strange move if Atheas had a daughter, as the established method of forging an alliance with Macedon was to marry a young daughter to Philip at his polygamous court.

The Scythian daughter theory encountered more hurdles: Herodotus’ colourful description of the Scythian pre-burial practice involved slitting open the belly of the deceased, cleaning it out and filling it with aromatic substances, after which the corpse was covered in wax before carting around for display to the tribe. In contrast, the Tomb II woman was cremated soon after death with no feminine adornments. Scythian female burials, however, were usually accompanied by jewellery: glass beads, earrings and necklaces of pearls, topaz, agate and amber, as well bronze mirrors and distinctive ornate bracelets. The Vergina mystery deepened.

The ‘battle of the bones’ on tomb identities continued for three decades. Arguments revolved around wounds evident or invisible on the Tomb II male bones when compared to the battle wounds Philip reportedly suffered. Wall paintings, entrance frescos of a hunting scene and even condiment pots found on the floor were heralded up as dating witnesses. But it was always debatable whether the twenty years between the death of Philip II and

his half-witted son Arrhidaeus could be discerned by interrogating the subtleties of relics this way.

The façade of Tomb II with the hunting-scene friese painted above the entrance.

Recurring questions filled academic papers: ‘did vaulted roofs exist in Greece in Philip’s reign? Was the hunting fresco, with its controversial depiction of lions in the quarry, inspired by the Persian game parks Alexander and his men witnessed on his campaign in Asia? All the ‘proofs’ for and against were argued both ways with equal dexterity.

By 2009, the ‘battle of the bones’ reached a stalemate when academics arguing the tomb identities ran out of debating ammunition.

The American Journal of Archaeology even called for a moratorium on ‘Vergina papers’ until new evidence came to light, noting that the polarised positions of archaeologists dated back to political rivalries from decades earlier.

The mysteries and controversies of the royal tombs remained as profound as ever: would there ever be a resolution?

The entrance to the subterranean Archaeological Museum of Vergina.

Unearthing the Family of Alexander the Great, the Remarkable Discovery of the Royal Tombs of Macedon by David Grant

is available from Amazon and all major online book retailers.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.