Augustus, the successor to Caesar

Tarquinius Superbus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, depicting the king receiving a laurel; the poppies in the foreground refer to the “tall poppy” allegory

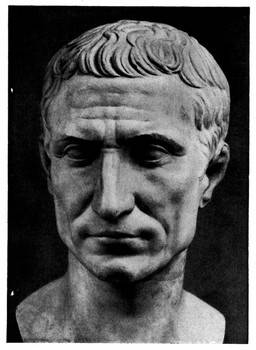

Bust of Caesar

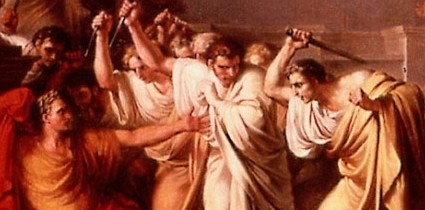

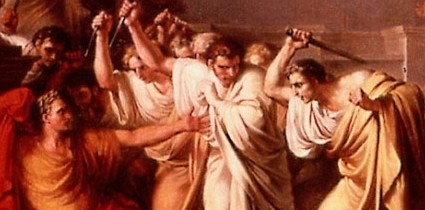

The Assassination of Caesar

Augustus, the successor to Caesar

Tarquinius Superbus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, depicting the king receiving a laurel; the poppies in the foreground refer to the “tall poppy” allegory

Bust of Caesar

The Assassination of Caesar

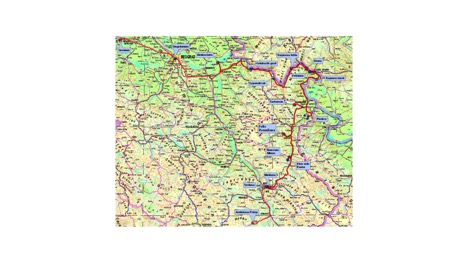

Routes of the Roman Emperors

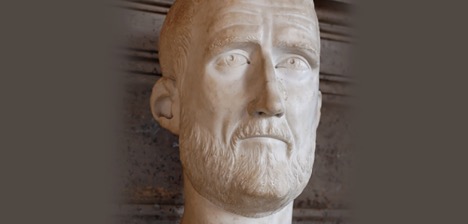

Trajanus Decius (Caesar Gaius Messius Quintus Trajanus Decius)

Probus (Marcus Aurelius Probus)

Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great, (Flavius Valerius Constantinus)

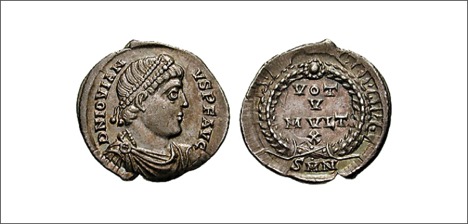

Jovian (Flavius Jovianus)

I’ve always held the belief that ancient history, in this case the history of the final years of the Roman Republic, are of such interest to readers because the subject matter can often be downright dramatic. Betrayal, bloodshed, assassinations- these were commonplace in the

Statue of Cato the Younger in the Louvre Museum

Statue of Cato the Younger in the Louvre Museumdays of ancient Rome. A political squabble, very literally, could often become a matter of life and death.

The tumultuous era of Roman history when the republic fell, and the empire rose, is a wonderful example of some juicy historical details. And while Caesar did usher in the beginning of the end for the Roman Republic when he crossed the Rubicon and, in his own words, “cast the die”, we should remember that the Republic did not go down without a fight.

That’s right dear reader! Today we are talking about the man who (almost) stopped Caesar. Along with none other than Cicero, he is often considered to have been one of the staunchest opponents of Julius Caesar’s and a great advocate for the Roman Republic. He is Cato the younger.

Much has been made of the struggle between Cato the younger (from here on referred to simply as “Cato”) and the soon to be dictator perpetuo. Was it a struggle between tyranny and liberty, good and evil? There are certainly some in history who think so. George Washington actually coordinated a showing of the 1713 play Cato, which dramatizes the final days of Cato, for his troops at Valley Forge as a means to inspire their vigor for liberty.

But first things first. Who was this defender of republican ideals? Who is Cato?

Much of what we know about this man comes from the Roman author Plutarch and his aptly titled Life of Cato. Plutarch tells us that as a young man, Cato was exceptionally bright, mature beyond his years and, even at a young age, steadfast and immovable in his convictions.

Plutarch tells us that as a young boy at a social event, Cato took part in a mock trial with other children. The children, playing as judge, jury, prosecution and defendant, supposedly found a good-natured boy guilty of some crime and locked him away in a chamber. The boy cried out to Cato for help and the young Cato responded by pushing the other children aside and freeing the prisoner.

It is fortunate that we so recently discussed Stoicism, dear reader, because it was said that, as a young man, Cato devoted himself to studying the Stoic philosophy and went about cultivating himself to become a great Stoic citizen. This was not unique to Cato the younger. His great-grandfather, Cato the Elder, had famously done the same thing only a few decades before.

As a result of his study of Stoicism, Cato lived in a very modest way. It was said he wore only the plainest clothing and ate only when necessary. He often subjected himself to the rain and cold in order to create a tolerance for discomfort. This adherence to the Stoic lifestyle is made all the more remarkable when we consider that Cato came from a rather wealthy family. He could have easily lived in luxury and decadence for the rest of his life if he so chose.

Perhaps because of his insistence to cultivate virtue through philosophical means, Cato gained a reputation for being exceedingly honest and for possessing an unshakeable resolve.

I know what you are probably thinking at this point. ‘Sure, that seems all well and good, but didn’t you mentioned something about Cato going toe to toe with none other than Julius Caesar?’

Indeed I did, dear reader! While we could easily spend days discussing the various stories surrounding Cato the younger, and spill untold amount of editorial ink in the process, let’s try to be a little more succinct and hit the highlights.

Shall we?

It was probably unavoidable that Cato would end up on a collision course with Caesar. After all, it was said that at the age of 14 Cato offered to kill the Roman Dictator, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, with the words…

Cato first locked horns with Caesar in 59 BC when

Cato was a vocal opponent of Julius Caesar, attempting to block his attempts at power for years.

Cato was a vocal opponent of Julius Caesar, attempting to block his attempts at power for years.Cato, now a member of the Roman Senate, attempted to block Caesar’s bid for consulship of Rome (the highest elected political office of the Republic).

Plutarch tells us that Caesar, returning from his military expeditions in Spain, wished to hold a triumph (a public spectacle celebrating Roman, military victories) while also running for the consulship in absentia.

The Senate was at first willing to grant such a request, but Cato vehemently opposed such a proposition. To prevent the Senate from voting on the matter, Cato filibustered on the Senate floor until nightfall. As a result, Caesar was forced to choose between a triumph and running for the consulship. He opted to abandon the triumph and ran for, and one, consulship of Rome in 59 BC.

Immediately following the election, Caesar allied himself with another influential Roman political player, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, known commonly as “Pompey”.

Plutarch tells us that together, Caesar and Pompey enacted laws that distributed land and grain to the poor. In doing so, Caesar was currying favor with the common people and, in the words of Plutarch, “stirring up and attaching to himself the numerous diseased and corrupted elements in the commonwealth. “

Cato regarded such legislation as politically motivated. While the poor benefited from the subsidized land and food, it was Caesar who really won out by boosting his reputation and allure among the common people. Cato viewed Caesar with a wary eye and believed him to be a mortal threat to the Republic.

For the next several years, Cato would make every attempt to block Caesar and deter his every ambition. When Caesar proposed another piece of legislation that would divide almost all of Campania, a region in southeast Italy, amongst the poor and needy, Cato again opposed this bill with his trademark stubbornness.

Plutarch tells us that Cato was so obstinate, in fact, that Caesar ordered the Roman guards to drag Cato from the Senate and place him in prison. Cato was lead from the room, speaking out against Caesar all the while.

The Roman historian, Cassius Dio, tells us that one Senator was so appalled by this use of force that he declared…

Cato was by no means the only opponent of Caesar’s. However, he was undoubtedly the most vocal and most unyielding. He was, in many ways, the common thread between every opposition that stood in the way of Caesar’s aspiration for power during the 1st century BC.

Despite his efforts, Cato was unable to prevent Caesar from attaining governorship of Illyria and the Gaul, a region in Northern Italy, as well as an army of four legions at his command. In the words of Plutarch, “Cato warned the people that they themselves by their own votes were establishing a tyrant in their citadel.”

It would seem Cato’s predictions would come to pass in 49 BC when Caesar, accompanied by the 13th Roman Legion, crossed the Rubicon intent on taking power from the Senate and abolishing the Republic.

It was now that all eyes were on Cato, the man who had warned of such an attack for years.

What followed was the Roman Civil War, sometimes referred to as “Caesar’s Civil War”. While Cato and the Roman Senate, bolstered by the armies of Pompey, would struggle against Caesar, the were ultimately defeated. Caesar’s victory would effectively end the Roman Republic and usher in the age of the Roman Empire.

What of Cato?

In 46 BC Cato found himself in Utica in Northern Africa. His armies defeated and his men slaughtered by Caesar, Cato had been backed into a corner. Caesar, now dictator perpetuo, offered to pardon Cato.

Cato however, refused to accept such a pardon. Doing so would be a tacit admission of Caesar’s legitimacy as a dictator, something that Cato would simply not allow. He committed suicide by impaling himself with a dagger, one final act of rebellion against the man who had ushered in the death of his beloved Republic.

By Van Bryan

Yes, that’s right dear reader. It most certainly wasn’t easy being a woman during the ancient times. The classical age certainly had a lot going for it. After all, it’s been argued that the ancient thinkers laid the foundation for over two thousand years of progress in fields like philosophy, literature, historiography, and theatre.

Aspasia of Miletus by Pierre Olivier Joseph Coomans

Aspasia of Miletus by Pierre Olivier Joseph CoomansHowever, progressive rights for women would not be listed among these accomplishments. Even in Athens, which was the intellectual and cultural hub of the classical age, women were often relegated to the home. Not allowed an education, the right to vote, or to participate in public discourses, the highest aspiration a woman could reasonably hope to achieve was to become a wife and bear children.

To an extent, we just have to accept that. It is rather easy for us now, blessed with thousands of years of societal evolution, to look back on the classical civilizations and think ourselves above them.

However, it takes a more nuanced mind to recognize that whatever advancements we have made as a species was only made possible because there were brave individuals, sometimes thousands of years in the past, who took the first meager steps toward progress.

Even with all that in consideration, we must realize a woman’s lack of rights in ancient times means that there are very few notable women who pop up on the classical timeline. After all, it’s hard to shape the direction of Western society when you are viewed as little more than property.

The ones who do catch the attention of history, therefore, are made all the more remarkable. Aspasia of Miletus was one such woman.

She is perhaps best described as a political woman who possessed a knack for rhetoric, a taste for philosophy, and the ear and heart of the most powerful statesman of classical Athens.

Aspasia was venerated and denigrated by the ancient writers. Viewed by some as a shrewd political player, by others as nothing more than a harlot, it was said that she was the lover of Pericles, the great aunt of Alcibiades, the supposed author of Pericles’ famous “funeral oration”, she was even reported to have taught Socrates a few lessons in philosophical argumentation!

Aspasia by Henry Holiday

Aspasia by Henry HolidayEven though all of our sources on this mysterious woman are less than reliable, perhaps even down right fallacious, the fact that such controversy surrounds her makes her a prime candidate for our inspection, and perhaps even admiration.

It was said that Aspasia was born to the historically important island of Miletus off the coast of Asia Minor sometime in the early fifth century BC. She must have been born to a wealthy family, for it is reported that she received a first-rate education, a rare thing for a woman in ancient times. It is important to note that these two statements are the only two pieces of universal concord surrounding Aspasia. That isn’t to say that everything else is hearsay, but it sure isn’t historical fact. We are just going to have to take a leap of faith on this one.

Anyway…where was I? Oh, yes!

We can be rather certain that Aspasia traveled to Athens sometime around 440 BC. One hypothesis suggests that she made the journey while in the company of her sister and new brother-in-law, Alcibiades II (grandfather to the famous general of the same name). If this hypothesis were true, it would explain how Aspasia came to know Pericles, a man who had close ties to the Alcibiades family.

Once in Athens, it is believed that Aspasia became a hetaerae (ἑεταίρα) and probably ran a brothel. Hetairai (plural form of hetaerae) were not common prostitutes. Rather, they were highly educated, highly sophisticated courtesans who would have been skilled at dance, song, conversation, and would have likely been present in the inner circles of powerful, affluent men.

Hetairai were probably the closest thing to liberated women during this time. They were allowed to pursue education, engage in civic debate, they even paid taxes! Additionally, Aspasia had the advantage of being a foreigner. This meant she was forbidden to marry an Athenian citizen. A consequence of this was that Aspasia would not have been bogged down by the restrictions placed upon married women.

She was free, therefore, to explore the societal landscape of the Athenian elite, and explore she most certainly did.

Aspasia is perhaps best remembered as the lover of Pericles. After the famed Athenian general divorced his first wife, he came to live with Aspasia. And while it is assumed that the two were never married, we do know that Aspasia gave Pericles a son who was bestowed with his father’s name.

Pericles was the dominant statesman of the age and was said to have loved Aspasia

Pericles was the dominant statesman of the age and was said to have loved AspasiaWhile we might assume that the statesman was attracted to Aspasia for her physical beauty, Plutarch tells us that he truly loved the woman and devoted himself entirely to her.

“…he (Pericles) took Aspasia, and loved her with wonderful affection; every day, both as he went out and as he came in from the market-place, he saluted and kissed her.” –Plutarch (Life of Pericles)

It is suggested, however, that Pericles might have been too devoted to Aspasia. It is likely that she advised, or otherwise persuaded, Pericles to take specific actions within his role as Stratego (general). Plutarch seems to believe that Pericles might have been motivated to declare war on the island of Samos simply because they were attacking Aspasia’s hometown of Miletus.

“Pericles, however, was particularly charged with having proposed to the assembly the war against the Samians, from favour to the Milesians, upon the entreaty of Aspasia.” –Plutarch (Life of Pericles)

While in the company of Pericles, it was said that Aspasia’s home became something of a hub for prominent Athenian figures. Generals, poets, even the philosopher Socrates was said to have visited Aspasia and Pericles’ home on a number of occasions.

Aspasia’s connection to Socrates is significant, because there is evidence to suggest that she might have been one of the philosophers first, and best, teachers in the art of rhetoric. Plato says as much within his dialogue, Menexenus.

“That I should be able to speak is no great wonder, Menexenus, considering that I have an excellent mistress in the art of rhetoric,—she who has made so many good speakers, and one who was the best among all the Hellenes.” –Socrates (Plato’s Menexenus)

It is even suggested within this dialogue that Aspasia, not Pericles, was the true author of the now famous “funeral oration”, found within the pages of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War.

“I heard Aspasia composing a funeral oration about these very dead. For she had been told, as you were saying, that the Athenians were going to choose a speaker, and she repeated to me the sort of speech which he should deliver, partly improvising and partly from previous thought, putting together fragments of the funeral oration which Pericles spoke, but which, as I believe, she composed.” –Socrates (Plato’s Menexenus)

We must consider the possibility that Plato’s use of Aspasia in this dialogue was intended as a humorous device. The idea of a woman teaching rhetoric to a man? Ha! How fanciful!

Aspasia and philosophers by Michel II Corneille

Aspasia and philosophers by Michel II CorneilleStill, the fact that Plato felt Aspasia’s name was worthy of mentioning at all speaks volumes for the type of reputation she must have had as a rhetorician.

Additionally, there are other sources that claim Aspasia was well versed in what would become known as Socratic dialogue, and may even have taught Socrates a thing or two about winning an argument.

Cicero tells us that Aspasia might have been the one to teach Socrates the rhetorical tool Inductio, or getting people to agree to a statement by having them agree previously to similar statements.

Cicero writes of a supposed conversation between Aspasia, a man named Xenophon (not the historian), and Xenophon’s wife.

“Please tell me, wife of Xenophon, if your neighbour had a better gold ornament than you have, would you prefer that one or your own?”

“That one, ” she replied.“Now, if she had dresses and other feminine finery more expensive than you have, would you prefer yours or hers?”

“Hers, of course,” she replied.

“Well now, if she had a better husband than you have, would you prefer your husband or hers?”

At this the woman blushed. But Aspasia then began to speak to Xenophon. “I wish you would tell me, Xenophon,” she said, “if your neighbour had a better horse than yours, would you prefer your horse or his?”

“His” was his answer.

“And if he had a better farm than you have, which farm would your prefer to have?”

“The better farm, naturally,” he said.

“Now if he had a better wife than you have, would you prefer yours or his?”

And at this Xenophon, too, himself was silent.

Then Aspasia: “Since both of you have failed to tell me the only thing I wished to hear, I myself will tell you what you both are thinking. That is, you, madam, wish to have the best husband, and you, Xenophon, desire above all things to have the finest wife. Therefore, unless you can contrive that there be no better man or finer woman on earth you will certainly always be in dire want of what you consider best, namely, that you be the husband of the very best of wives, and that she be wedded to the very best of men.” –Cicero (De Inventione)

By having her listeners assent to questions with similar circumstances, she entraps her opponent into conceding a later, sometimes embarrassing, admission that proves her point. This was a technique that Socrates would make famous several years later.

Aspasia and Socrates by Nicolas André Monsiau

Aspasia and Socrates by Nicolas André MonsiauIt is perhaps unsurprising that Aspasia, with her keen political mind and ability to outmaneuver men during conversation, would garner some personal attacks.

Plutarch tells us in Life of Pericles that the Athenian comic playwright Cratinus referred to Aspasia as “a harlot” in one of his plays. Additionally, she was put on trial by the comedian Hermippus. She was accused of impiety and of corrupting the women of Athens with her strange and unhealthy life style.

Interestingly, these charges were remarkably similar to the ones lodged against Socrates in 399 BC. Unlike Socrates, Aspasia was saved from execution by a rare emotional outburst from Pericles.

Other ancient critics, Plutarch only refers to them as “some of the Megarians”, believed that many of Pericles’ military blunders were actually the fault of Aspasia. A woman, after all, ought to have no place in military affairs!

It is suggested, however, by the author and modern historian Madeline Henry that Aspasia’s critics would have had their own personal reasons for attacking the outspoken woman. After all, a political woman in the age of classical Athens was a subject of great frustration for many powerful men.

Even with her critics, Aspasia enjoys a sterling reputation in our modern age. She was arguably one of the most important intellectual figures during the height of Athenian power, and she was undoubtedly the most remarkable woman to have ever lived during that age.

She is perhaps best described by Lucian in his a Portrait Study…

“We could choose no better model of wisdom than Milesian Aspasia, the admired of the admirable ‘Olympian’; her political knowledge and insight, her shrewdness and penetration, shall all be transferred to our canvas in their perfect measure.

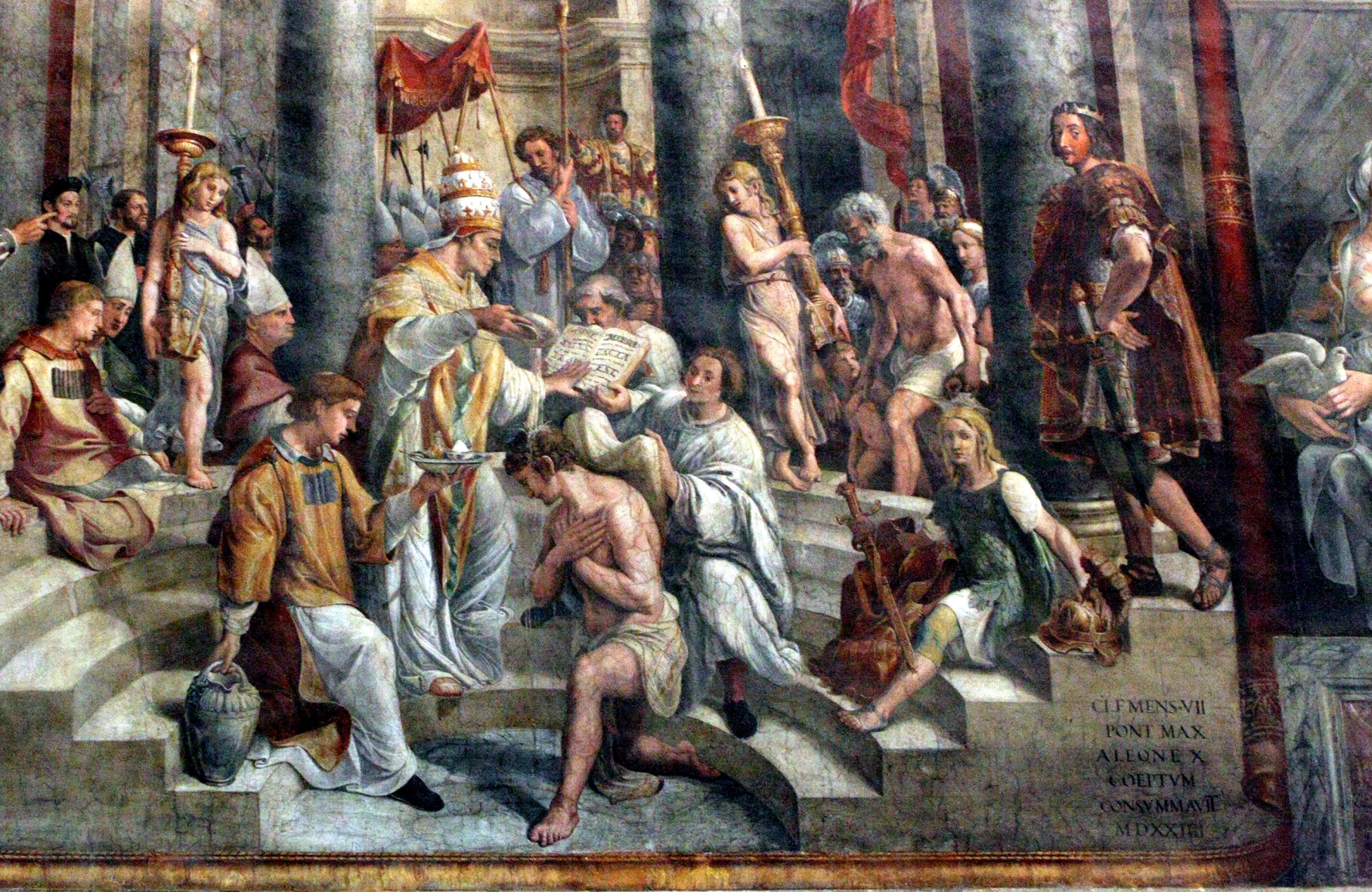

The assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March – March 15, 44 BC was an epochal event. It’s not merely a story in Shakespeare’s great tragedy but an actual historical occurrence.

The real assassination, unlike the Shakespearean drama, had a decidedly military shape. The leading assassins included some of Rome’s greatest generals. The conspirators brought a troupe of gladiators to the Senate House that day, men who doubled as a paramilitary force to help them in case Caesar and his supporters put up resistance. Rome itself was full of soldiers, mostly armed veterans but also including a legion under one of Caesar’s loyalists. Caesar’s stay in Rome from autumn 45 BC through spring 44 BC was only an interlude between two military campaigns. Having emerged victorious from the Civil War (49-45 BC) Caesar now planned a massive military expedition in the east. He was scheduled to depart on March 18, 44 BC. The conspirators struck at nearly the last possible moment before Caesar would get swallowed up by the army and be protected by a commander’s bodyguard.

The real assassination, unlike the Shakespearean drama, had a decidedly military shape. The leading assassins included some of Rome’s greatest generals. The conspirators brought a troupe of gladiators to the Senate House that day, men who doubled as a paramilitary force to help them in case Caesar and his supporters put up resistance. Rome itself was full of soldiers, mostly armed veterans but also including a legion under one of Caesar’s loyalists. Caesar’s stay in Rome from autumn 45 BC through spring 44 BC was only an interlude between two military campaigns. Having emerged victorious from the Civil War (49-45 BC) Caesar now planned a massive military expedition in the east. He was scheduled to depart on March 18, 44 BC. The conspirators struck at nearly the last possible moment before Caesar would get swallowed up by the army and be protected by a commander’s bodyguard.

It is not surprising that a group of Roman Senators (more than sixty), many of them also military men, gathered together to kill Caesar. Caesar threatened to change their lives in ways that mattered – and that hurt. Caesar was undertaking a series of fundamental reforms in Rome and its empire. He wanted to downplay the power of the city of Rome and its ancient elite and to share power with new elites in the provinces. He also wanted to reduce the power of the Roman people in the annual elections to choose public officials. The result would be more efficient and fairer to the tens of millions of people who lived in Rome’s provinces but it threatened the privilege and power of both mass and elite in the city of Rome. And it threatened to turn a republic into one-man rule, which few in Rome wanted. Caesar was a visionary but the Romans held back.

A visionary leader has a hard time persuading the public to accept change. This is as true today as in any period of history. For Caesar it meant overcoming the legacy of the Civil War in which he had won power. He had a hard time steering between crushing his enemies and conciliating them. Caesar tried to strike the right balance but it was a daunting task. He was arrogant where he should have been humble and merciful where he might better have used force.

A visionary leader has a hard time persuading the public to accept change. This is as true today as in any period of history. For Caesar it meant overcoming the legacy of the Civil War in which he had won power. He had a hard time steering between crushing his enemies and conciliating them. Caesar tried to strike the right balance but it was a daunting task. He was arrogant where he should have been humble and merciful where he might better have used force.

Caesar said that he wanted to forgive his enemies, not execute them, but the very act of making them ask for his forgiveness was humiliating to them. He said that he had no ambition to be a king but he accepted the title of Dictator in Perpetuity – in effect, Dictator for Life. Although married he was having an affair with the queen of Egypt, Cleopatra, who had an illegitimate son who, she said, was his and who was called Caesarion, that is, “Little Caesar.” In March 44 BC she lived in Caesar’s villa in the suburbs of Rome. He planned a vast, three-years-long military expedition to culminate in the conquest of Parthia, as the Persian Empire was known at the time, which would have him follow the footsteps of the ancient world’s greatest conqueror, Alexander the Great.

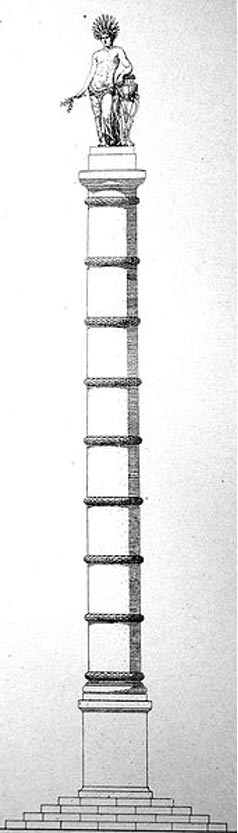

Caesar seemed to be taking over much of the Republic in the name of his own family, the Julian clan. He built a new forum, a new Senate House, a new Speaker’s Platform, a new law-court and administration building, all named after him; other plans were in the works. He appointed his grandnephew, Octavian, as his “Master of the Horse,” the dictator’s second-in-command, on his war against Parthia in 43 BC, even though Octavian was only 18 years old, a shockingly young age in Rome to hold such a high office. Caesar accepted an unprecedented range of honors including divination: the Senate declared Caesar a god.

All of this persuaded many Romans, senators and ordinary people alike, that Caesar wanted to be king in all but name. And that was unacceptable to the many believers in Rome’s republican government.

Caesar was fatalistic about the danger of assassination. He knew it was a possibility but he was a decorated soldier who did not want to live his life in fear. He dismissed his official bodyguard but, to deter attack, surrounded himself with tough men and former soldiers. Only senators could enter the meeting hall, however, so Caesar was vulnerable at senate meetings. His enemies knew that, which is why they struck at a meeting of the Roman Senate on the Ides of March – March 15, 44 BC.

“Death of Julius Caesar” By Vincenzo Camuccini

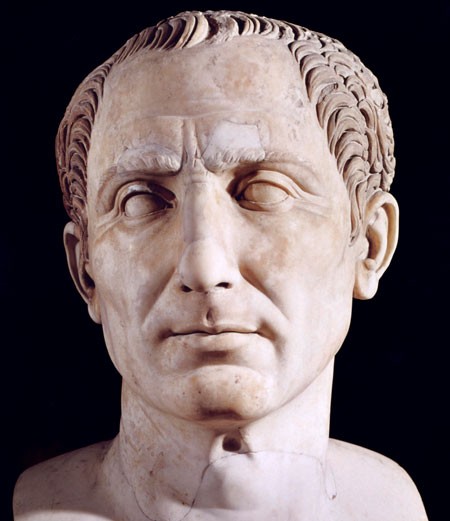

After Caesar’s death his mantle fell to Octavian, whom Caesar had secretly adopted as his heir, six months before the Ides of March. Although young, Octavian proved to be a genius, with all the ambition, practical wisdom, cunning, tenacity and ruthlessness of his great-uncle. Eventually, after a decade-and-a-half of war and diplomacy, Octavian won supreme power in the Roman world. In 27 BC he took the name Augustus, which is how we know him today.

Augustus was Rome’s first emperor but he learned a lesson from Caesar’s mistakes. He took the danger of assassination seriously, he kept a bodyguard, and made sure not to inflame his enemies. He never called himself emperor, king or dictator. Instead, he preferred the title of Princeps or “First Citizen.” “Augustus” itself means something like “Reverend.” He even declared that he had restored the republic, which was simply untrue. Yet Augustus had the  wisdom and self-restraint to hold back. Although he grabbed the lion’s share of power in Rome he did leave some authority to the Senate, in order to give them a stake in the system.

wisdom and self-restraint to hold back. Although he grabbed the lion’s share of power in Rome he did leave some authority to the Senate, in order to give them a stake in the system.

The other thing that Augustus did, sad to say, was to kill his enemies rather than forgive them, as Caesar had done. Rather, he took the advice that Machiavelli would later offer in The Prince, that is, to massacre his opponents at the start of his reign and then, having made his point, to rule with kindness. So, for example, little more than a year after Caesar’s death, Octavian (as Augustus was then) joined hands with Mark Antony to pass death sentences on their enemies and to confiscate their property. Among those killed in the ensuing reign of terror was Cicero, Rome’s greatest orator and Octavian’s former ally. Cicero and Antony were enemies but the coldblooded young Octavian did nothing to save Cicero from Antony’s vengeance. More years of civil war followed in which many more of Octavian’s enemies fell. By the time Octavian became Augustus in 27 BC, no major enemies were left alive to oppose him.

To the world’s great fortune, Augustus then used his political genius to create an era of peace – the pax Romana, the Roman Peace, one of the greatest periods of prosperity and cultural achievement in the history of the West. It was not perfect – slavery, for instance, thrived – but it was good.

There are many lessons to be learned from the stirring and terrible events of the era of Caesar and Augustus. One is the law of unintended consequences: the men who killed Caesar on the Ides of March thought they were saving the Republic, not hastening its end. The other is the need for political sagacity, for fine-tuned political skills, in order to persuade people to accept reform. And finally, we can’t overstate how fortunate we are to live in a society where political disagreements are settled by debate and not by arms, by ballots and not bullets. May it always be thus.

Barry Strauss teaches history and classics at Cornell. He is the author of The Death of Caesar: The Story of History’s Most Famous Assassination (Simon & Schuster: March, 2015). Follow him on Twitter @barrystrauss.