When I was about twenty five years of age, I read Plutarch’s Lives. I did so because I came across it in a used book shop, and it had a nice leather bound cover, and because it seemed to be a history of the lives of some very interesting classical characters.

I enjoyed this tome immensely, reading all of the biographies therein.

Third Volume of a 1727 edition of Plutarch’s Lives, printed by Jacob Tonson

Yet, it was in the account of Alcibiades that I was particularly struck. Struck so intensely that I put down the book and was changed forever.

My thoughts for several days returned again and again to the events I had read, and I felt as though new perceptions of reality were breaking through the gloom of modernity, like light through a dense canopy of forest.

This is, I believe, something which happens to everyone who reads the classics.

You may do so out of some frivolous notion of adding to your retinue of knowledge. Perhaps you are obliging a quirky activity which might arm you with interesting talking points or insights on other world views. Often it is even just to be able to say that you read Aristotle or Virgil because it sounds romantic.

What you don’t expect when you undertake that adventure is the arresting, brain-altering impact of being exposed to the thoughts of classical authors.

You picked up Marcus Aurelius on a whimsy, and five pages in you become catatonically quiet—stupefied with admiration.

The clarity of their ideas, the romantic and primordial fire of their unrestricted opinions, forged in the furnace of the early ages of recorded history. This hits you between the eyes like a diamond bullet.

And this was the effect Plutarch had on me, at that specific time in my life.

I was deeply affected by his all-too-human portrayal of Alcibiades. The realization of a man’s ego struggling against the pitfalls of events thrown at him by destiny.

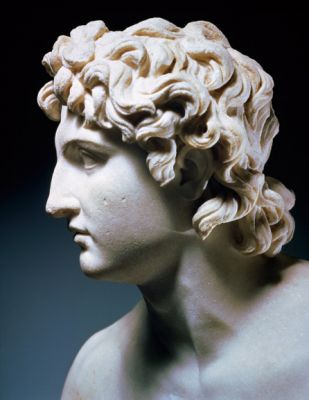

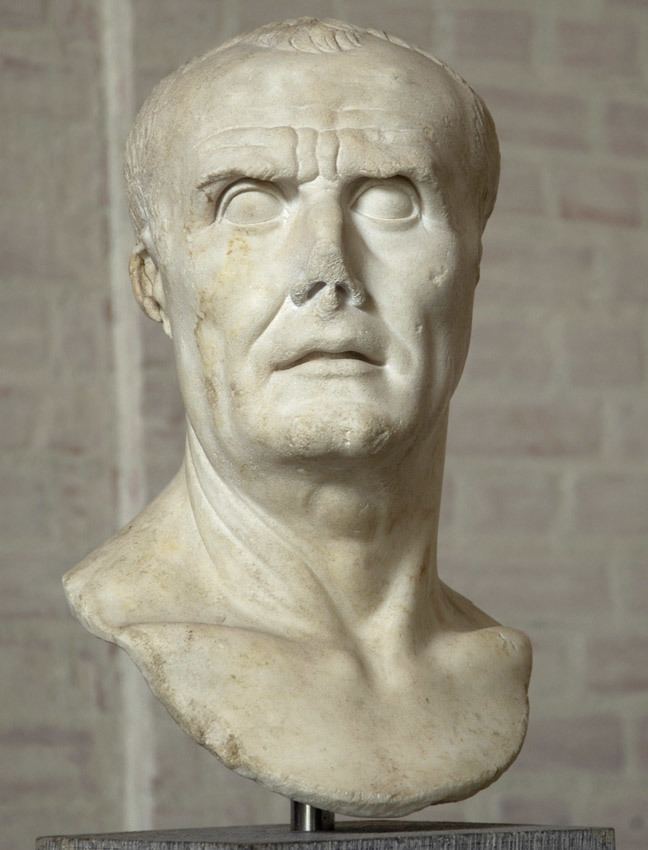

A Roman copy of a 4th century BC Greek bust of Alcibiades, in the Hall of the Triumphs, Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Resilience comes to mind. Resourcefulness. His life seemed a highly dramatic hamster-wheel of egotistically swaggering into outrageous scenarios, winning the day, then being run out of town for reasons related to that same ego.

You might say he was something of a freebooter. He was changeable as a survival trait. He showed tremendous courage and strategic ability, and died defending his home, a dagger in his hand.

A figure who shaped history—who is history—outrageous both in his exemplary traits as well as his character flaws.

Alcibiades was, even in youth, known to be very arrogant and held a high opinion of himself. He was famously handsome. He was well known for oratory and for an ability to win people over, a skill he employed throughout his life.

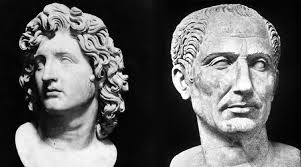

He also proved himself repeatedly as a shrewd and capable military commander. He was a pupil of the great

Socrates, no less, who had also saved him in war. He was brought up during the trial of Socrates as an endemically corrupt character whom even Socrates could not teach morality.

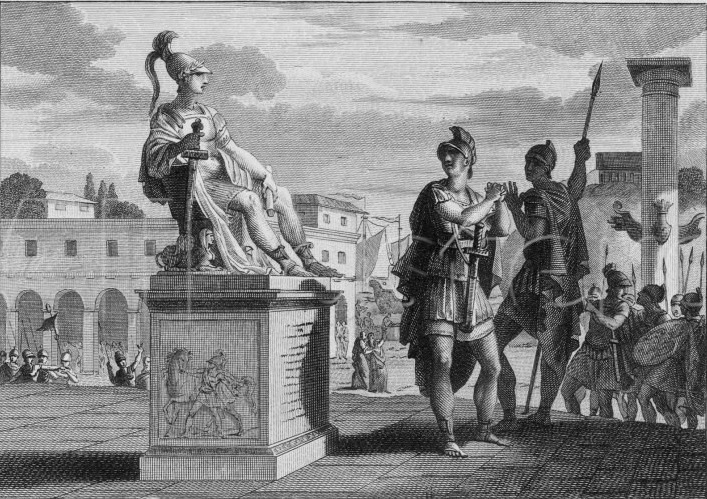

Jean-Baptiste Regnault: Socrates dragging Alcibiades from the Embrace of Sensual Pleasure (1791)

His initial rise to prominence came from his aggressive manipulation in Athens to arouse

conflict with Sparta. He did this through creative, conniving, influential oration, and outrageous double dealing.

Quite deviously he would meet with Spartan emissaries in private before their presentation to the Athenian assembly, convincing them with his charm to say something they didn’t intend at the assembly, so that he could then accuse them of capriciousness and foment ill will towards Sparta.

When he later rose to the status of a general in Athens, he was accused of blasphemy in the vandalizing of plinths dedicated to Hermes.

Whether he was actually guilty or not, history fails to relate.

What we do know is that these accusations were made just as he embarked on a

Sicilian expedition as general and, being away, was unable to defend himself against public opinion regarding this blasphemy. Combined with his notoriety for questionable morals, the accusation grew into a fervor.

And so, while away defending his nation in war, he was condemned to death and his property was confiscated.

Many historians find it unlikely that he would have committed the vandalism attributed to him. It was most likely a case of rankling the feathers of various elites, a difficulty which plagued his life and career many times over.

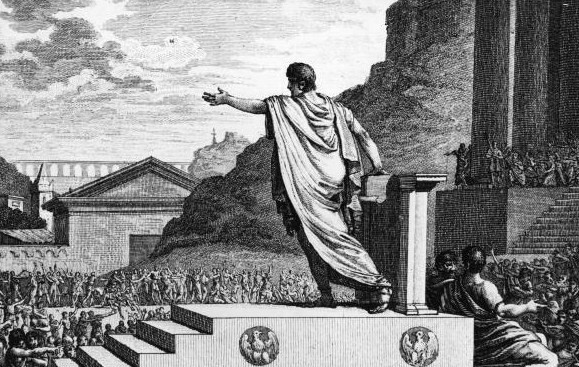

Men do not rest content with parrying the attacks of a superior, but often strike the first blow to prevent the attack being made. And we cannot fix the exact point at which our empire shall stop; we have reached a position in which we must not be content with retaining but must scheme to extend it, for, if we cease to rule others, we are in danger of being ruled ourselves. Nor can you look at inaction from the same point of view as others, unless you are prepared to change your habits and make them like theirs.

– Alcibiades’ Oration before the Sicilian expedition

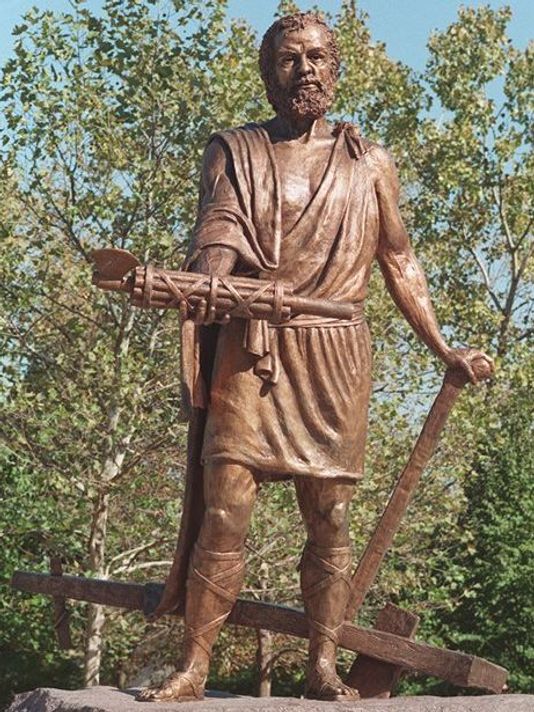

Socrates Rescues Alcibiades at the Battle of Potidaea, 1797, Antonio Canova.

But those that sought his demise would not have to wait long to regret it, as clever Alcibiades employed strategy to the chess board of his life in all aspects, and all conditions.

While on campaign in Sicily (which, as usual, was going well for him) he got word that he was condemned to death at home. Without so much as batting an eye he switched allegiance and gave strategic information to the Sicilians, turning the tide of that conflict against the Athenians.

Here we find actions typical of Alcibiades.

You might say it was traitorous. But had they not unjustly deigned to kill him?

You might say it was extreme. But what else could he do that would both ensure his survival and enact revenge?

The unstoppable nature of this man’s survival instinct, where unblinking retribution is delivered with aplomb, against unjust antagonizations, itself due to the extremes of his character to begin with. The daring. The ridiculous gall. The power of personal will against dramatic twists of fate.

Whatever you think of his switching of allegiance, you have to admit the man was just quick on his feet when it came to saving his own skin!

After this turn of events, Alcibiades disappeared at Thurii. Then, unrelenting in his strategizing, he contacted those Spartans who he had spent his early career prejudicially scheming against. He did this, as Plutarch tells us, by “promising to render them aid and service greater than all the harm he had previously done them as an enemy”. This he offered in exchange for sanctuary.

The Spartans, desiring victory, welcomed this former enemy.

In this duplicitous scheme we see Alcibiades exhibit his ability to not only make grandiose propositions, but actually succeed at carrying them out. Wily enough to survive upon the eddies and currents of fate, a river in which we are all cast adrift. The spinning of the yarn of Necessitas, who sits above all divinity as unshakable destiny. And so, Alcibiades became then as a Spartan, living frugally, drinking the black broth in the communal dining halls.

And there too he excelled as a general and military commander. Somewhat typically, he favored unconventional tactics, frequently winning cities over by treachery or negotiation rather than by siege. As promised, he became a worse enemy to Athens than any other Spartan general.

Alcibiades: Can’t live with him, can’t live without him!

Our party was that of the whole people, our creed being to do our part in preserving the form of government under which the city enjoyed the utmost greatness and freedom, and which we had found existing. As for democracy, the men of sense among us knew what it was, and I perhaps as well as any, as I have the more cause to complain of it; but there is nothing new to be said of a patent absurdity—meanwhile we did not think it safe to alter it under the pressure of your hostility.

– Alcibiades’ Speech to the Spartans, as recorded by Thucydides (VI, 89); Thucydides disclaims verbal accuracy

But, as usual, this favorable situation was not to last for poor Alcibiades. In spite of his invaluable martial contributions to the Spartan cause, Alcibiades fell out of favor with the 18th Eurypontid king of Sparta, Agis II, who hosted him in exile on account of Alcibiades having seduced the kings wife, and possibly fathering a child with her.

Yes… you read that right.

A Spartan admiral was sent to Alcibiades on orders to murder him, but Alcibiades got wind of this and, in typical fashion, immediately defected to a new camp: The Persians.

Silver-tongued Alcibiades won the trust of the Persian satrap Tissaphernes and was well received.

Coinage of Achaemenid Satrap Tissaphernes, who received Alcibiades as an advisor. Astyra, Mysia. Circa 400-395 BC

He immediately did as before, and became a scourge to his former ally and host, enacting his revenge on the Spartans by using his knowledge of their cause to inflict immeasurable injury.

But among all this changing of allegiances the clever general became homesick.

His notoriety both in courtly influences and military strategy made him an asset to any welcoming kingdom. He knew democratic Athens would never agree to his recall after the charge of blasphemy.

So this man, this outrageous fellow, proposed to Athenian leaders that they not only allow his return to his homeland (which he had successfully warred against) and reinstate him, but that they also change their system of government and install an oligarchy to facilitate this. In return he would bring with him Persian money, triremes, and his personal influence with Tissaphernes.

Of course, this amazing proposal was agreed to. Such was his power, and the legend of his abilities, and his self-confidence. So Athens changed their system of government at his behest, and welcomed him back as a great general.

This was Alcibiades. What can you say of him? What can you make of this story?

However, during the war with Sparta, it became obvious that in fact he had no influence with the Persians whatsoever.

And so from that point on his authority in Athens depended on what he actually could accomplish rather than on what he had promised to do.

Fortunately, he did go on to have significant military success. But despite that, having misunderstood his standing with Tissaphernes, Alcibiades went to meet with the satrap only to be arrested upon arrival. Yet, typical of our swashbuckler, he was captured for only a month before escaping, and resumed his command in Athens, and went on to command many more defeats against Sparta and Persia, both his former accomplices in war.

Then Cyrus the Younger (son of Darius II of Persia) became the new ruler of Persia and began to financially support the Spartans. This turn of events finally led to Alcibiades’ defeat in a major battle and, combined with further false accusations brought against him by his enemies, his dethronement from a position of popular glory and exile once more.

He never again returned to Athens, but his removal and that of his allies (who happened to also be the most capable commanders in Greece) led to Athenian surrender only two years later, after their complete defeat at Aegospotami.

According to Plutarch, Alcibiades lived out the remainder of his days in Phrygia with his mistress Timandra, where he would later be killed on commands from the Spartan admiral

Lysander.Alcibiades died defending his home, which assassins had set on fire, rushing to meet his enemies with a dagger in his hand, where he was shot down by their arrows.

La mort d’Alcibiade. Philippe Chéry, 1791. Musée des Beaux-Arts, La Rochelle.

He died as passionately as he lived, refusing to go down without a fight.

So, how can we sum up the dynamic character of Alcibiades, as related to us by Plutarch?

Certainly morally questionable (for a Greek) but indomitable, never failing to live fully, like a strong vine reaching for the warm sun. Full of life.

He was dismissive of safety and complacence where the opportunity for glory arose. His glory, or name, however, was secondary to his material survival. At no point did he appear to suffer from self-doubt or the pressures of custom, meeting both success and failure with a clever counter, always one-upping his enemies.

Alcibiades’ military and political talents frequently proved valuable but his propensity for making powerful enemies ensured that he never remained in one place for long. Whenever he fell out of favour it was partly due to his roguery and arrogance, and partly due to circumstance. It was hardly for reasons you might consider evil.

The actual lessons to learn from the life of Alcibiades rest not solely in unrelenting ferocity or personal courage. It is not just his flexibility in the face of unexpected troubles.

Rather, it is the root understanding of reality that we admire in classical thought and in much of classical philosophy.

It is the acceptance of the limits of nature, of her unquestionable authority. Acceptance that is tempered by an idealized exploitation of the possible, within nature’s guidelines.

This is the test of the limits of man’s abilities. The supremely creative, the cunning, and the courageous react as needed to not only survive but thrive within a labyrinth of unexpected obstacles, twists of fate, and traps.

We might summarize the lesson of his life as this: unrelenting artfulness, unshakable self-belief, and acceptance and tenacity in the face of nature’s never-ending struggle.

All of us need, from time to time, to make life changes. I was at a certain point in my life when I picked that book up, and at another when I put it down.

In the life of Alcibiades I gleaned the wisdom that nothing was going to happen in life unless I took action myself—unless I discarded that which was contrary to my nature, even at great social or personal difficulty, in order to enact what is vital to my nature.

Alcibiades Being Taught by Socrates (1776), by François-André Vincent.

I promptly closed that book, and began discarding things that were impeding me from meeting uninfluenced instinctual goals. Goals not necessarily unusual, but nevertheless relatable only to me.

If you have a goal, and see unstoppable forces standing in your way, particularly social ones, they can be overcome.

It may come at a cost, all things do.

You will always have enemies, and you will always discover new ones where you least expected. But don’t surrender these primal goals in the face of either danger, disapproval, or short term loss.

When you go outside, and feel the deepness of the earth, and the cold pinpricks of rain and the sound of wind in the trees, the illusions of modernity are dispelled. The same can happen when reading classic literature.