Written by Visnja Bojovic, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Ever since there were people and places, there has been a desire for other, different people, and ideal, perfect places. This concept is called utopia, a word that has its origin in ancient Greek, as a compound of the word οὐ (ou, ”not”) and τόπος (topos, ”place”). Even though unmistakably Greek, this word was developed much later, in 1516 to be exact, by Thomas More.

In the same manner that the dreaming of a better world is almost as old as the world itself, puns are almost as old as the words themselves. Thus, when coming up with this concept of no-place, Sir More was playing with the word eu-topos, which meant ”a good place”. Coincidence? Let’s see.

Even though the concept of utopia, or utopian literature, was not invented by the Greeks as such, it was present in Greek thought and literature starting as early as in Homer’s works. (the land of Phaeacians in the Odyssey).

Claude Lorrain, Port Scene with the Departure of Odysseus from the Land of the Phaeacians (oil on canvas, 1646; Louvre, Paris)

The main characteristics of utopia are the lack of existential worries that occupy our minds every day, the lack of corruption and injustice, and, most importantly, its location that is remote either in the sense of space or time.

Thus, we have the so-called nostalgic utopia, such as the one found in Hesiod’s didactic poem Works and Days, where the distant past is referred to as golden and considered perfect and irretrievable. There are also completely fictional utopias, in invented lands with invented people (as the one in the Odyssey).

Another distinction, and the more important one if you ask me, is that of the utopias of reconstruction, and the utopias of escape. In the latter, a protagonist is sick of the actual world, and his only wish is to escape to another, typically, non-existent one. This kind of utopia does not have a goal to change the world or come up with a new one.

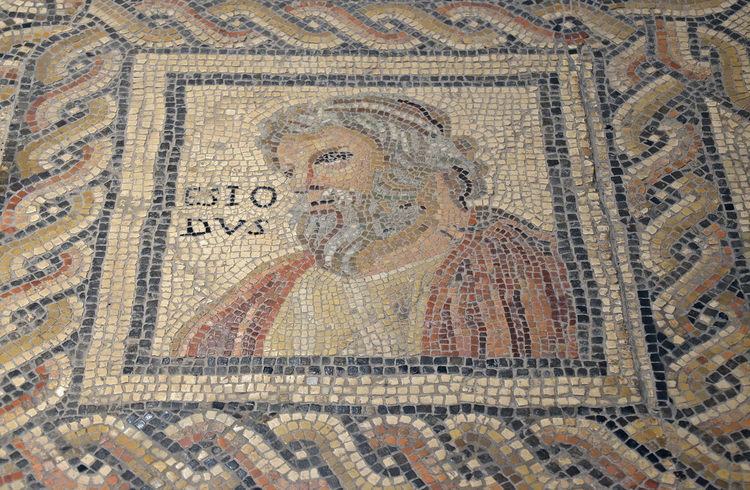

Portrait of the Greek poet Hesiod (ESIODVS) on the Monnus mosaic from Augusta Treverorum (Trier), end of the 3rd century CE.

In the former, on the other hand, as the name itself indicates, the author intends to reconstruct, or reinvent the world. The most well-known example of this is Plato’s ideal state in the Republic. Plato comes up with a whole new system of government and distribution of goods, where he implements a radical change of everything in favor of equality. However, as it turns out, ”all the animals are equal, but some are more equal than the others”. Thus, Plato gives the advantage to philosophers, who should be rulers, because they are wise and, as such, capable of governing the state perfectly.

So far, I have mentioned the main types of utopia that can be found in ancient Greek literature. However, we encounter complications when trying to classify all the utopias of one specific author into these categories. There were, and still are, many disputes regarding the goal of constructing the utopias of this author. As you’ve probably guessed, I am talking about Aristophanes, in whose works we can identify traces of the utopian concept.

These utopias tell us a lot about the problems that the Athens of Aristophanes’ time was facing, and there was quite a lot of them. For example, it was obvious that in Peace, where the main plot is a great desire for peace in Athens devastated by constant war and conflict, Aristophanes was trying to point out the pointlessness of wars and its disastrous effects. Similarly, in the Clouds, the criticism of sophistic teaching and the dangers of its popularity is fairly obvious.

Theatre of Dionysus, Athens — in Aristophanes’ time, the audience probably sat on wooden benches with earth foundations.

However, what I think is far more important, and far more profound is the implicit criticism that Aristophanes carefully implemented in his comedies, step by step as the plot advances.

Assembly Women (Ecclesiazusae)

In this comedy, the protagonists are women sick of men not governing the state properly and deciding to take matters into their own hands. Their leader is a woman named Praxagora, who introduces the idea of completely reversing the established order. She introduces the communism of property, where all the property was to be shared, and everyone was to be absolutely equal. All this sounds great in the beginning, but in the second part of the play, Praxagora mysteriously disappears, and human nature begins to take its toll.

Therefore, as soon as the new order is established, we can see that the only people willing to share are the ones who have nothing or very little to share and that even the ones who were against the new system are rushing to get their part of the cake.

Muse reading, Louvre.

Moreover, not only did Praxagora dictate that property was to be held in common, but that sex and family would be communal matters as well. This meant that the family was to be abandoned as the principal unit of society, and the children would belong to the state.

As for sex, the right to choose was to be given to the old and ugly to the detriment of the young and beautiful. Thus, we have a scene where a young couple wants to be together, but they are not able to do so, because a few old women are fighting over the young man. It soon becomes clear that the sexual desire needed for intercourse with a young person will be gone after all the desires of old people are fulfilled.

Birds

In Birds, we have two Athenian men fed up with life in Athens degraded in every sense by war and other problems. They are in search of Tereus, an old king who was transformed into a bird, to help them find a better place to live.

Vase with scene from Aristophanes’ Birds.

After some difficulties, they manage to form a city in the sky, along with other birds, and along with promises of everything opposite to Athenian customs, including the walls around the city. However, the first thing that is done in the new city is raising the walls. One of the Athenians goes outside of the city to guard it, while the other one, Pisthetaerus, stays and turns into a dictator who deems himself greater than Zeus.

The Ultimate Protagonist: Human Nature

Both of these comedies start as classic utopias with protagonists having strong desires to change the order of things in pursuit of establishing firm moral values. However, when they actually start doing it, human nature comes in as the most important protagonist and reverses the affairs either to their previous state, or an even worse one. Even though Aristophanes new that the world is far from ideal, he managed to show that the ideal is usually unreachable and that we have no choice but to operate inside of what we already have.

One comment

During the whole human existence, people are trying to do “business”, because that is our nature. So this is the reason why business ethics appeared. As an Aristophane, I consider it is an essential element of well-being. So it refers to the standards for morally right and wrong conduct in our deeds. check this out claims that law partially defines the conduct, but “legal” and “ethical” are not necessarily the same. Business ethics enhances the law by outlining acceptable behaviors. A man’s utopia set up in his head, as many historical essays demonstrate, can have a different impact on others around him…

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.