Written by Jacek Czarnecki, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

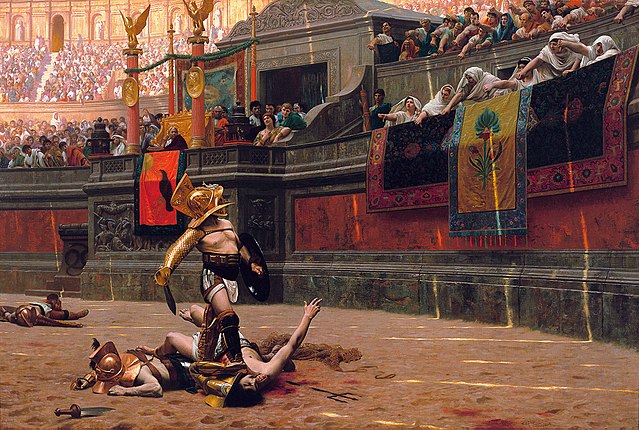

Fearless warriors battling each other to the death while providing entertainment to a blood-thirsty audience: that’s how most people envision the Roman gladiators. However, this image is shaped more by film than historical reality.

The first gladiator games took place in 264 BCE, although the origins go back much further, possibly to Campania, where they were found in the funeral processions of aristocrats. There, fights were organized to ease the passage of the deceased relative into the afterlife and at the same time display wealth and power of the family organizing the event, since they paid for everything.

Once gladiator fights became a more mainstream form of entertainment, they took place in whatever large public space there was available, but with time they found their home in amphitheaters. These amphitheaters started out wooden, but eventually became more fancy—the first stone amphitheater appeared in Pompey in 55 BCE. Due to their high cost, not all cities had amphitheaters, so in many small towns and cities fights were watched in alternative spaces, such as the Forum, theaters (especially in Greek cities), and in general, in large open spaces.

Eventually, amphitheaters became synonymous with gladiators and proliferated to the point that by 3rd century there were over 200 of them throughout the empire. The most famous and grandiose of them all was Rome’s Colosseum, containing some 45,000 seats and an additional 5,000 places for the standing spectators.

Although the price of admission was high for most Romans, free tickets were regularly available courtesy of the emperor, senators, or sponsors of the entertainment (this boosted their popularity with the people).

However, free goodies did not stop there – spectators had an opportunity for various other gratis items, including meat from slaughtered animals in the arena. This might sound strange today, but in some ways it is very similar to our modern notion of entertainment. How many listeners call radio stations on a daily basis hoping to win free tickets to upcoming events? And how many further hope to participate in some half-time games or drawings, craving to get prizes and goodies for the evening?

Today, our expectation of prizes are different, but this goes both ways — ancient Romans would certainly not appreciate winning a stuffed animal! Also like today, concession stands with what we would consider fast food were usually present at these events (if you were lucky enough to actually set foot inside the Colosseum).

The morning program was followed by lunchtime executions in various forms, such as crucifixion or death by wild animals (introduced as a new sentence in 167 BCE by Aemilius Paullus). Although it is important to note that usually criminals and slaves would be tortured in these events, Roman citizens would have a swifter death by the sword – another barbaric practice many assume is limited to the ancient world. The reality is, public executions existed until rather recently, ending in America and France as late as the 1930s. Some countries, such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Somalia and North Korea, still have public executions.

Finally, in the afternoon came the long-awaited gladiator fights. Just like today’s main events, which have opening acts that build anticipation and excitement, so did the Romans. There were mock fighters called paegniarii who used sticks and whips, as well as lusorii who used wooden weapons.

At last came the main event of the day: the gladiators themselves. People had been waiting days in anticipation, as attractive advertisements of future fights were posted all over the city on walls and beside main roads.

To keep interest high, the names of newly participating gladiators were added daily just before the event – an important form of advertising, as many spectators had their own lineup of gladiators they wanted to see perform live. It was similar to what many concerts venues do today by announcing guest performers only a few days prior to the event.

Gladiator fights, and sports in general, seem to have been widely-celebrated events in ancient Rome. In fact, at one point, a gladiatorial contest between the city of Pomeii and Nuceria resulted in a riot between the spectators, causing Emperor Nero to close the amphitheater in Pompeii for ten years as punishment. A soccer fan living in England in the 1970s would certainly not find this bizarre at all — even today, various soccer clubs are occasionally punished for the behavior of their fans.

The city of Rome boasted four chariot racing teams named after their team colors, each with its own fan club. Sporting competitions were full of energy in the ancient Roman world. Athletes were so popular that they were portrayed on various objects including motifs in art, mosaics, and clay lamps.

Gladiators were so popular that even some emperors and other elites volunteered to fight as gladiators, resulting in various laws to prevent the situation from getting out of control. Gladiators had an unusual position in society. Despite being at the bottom of the social hierarchy — many of them were slaves, criminals, deserters of army, or captured prisoners —they symbolized Roman virtues of masculinity, bravery, and fearlessness in the face of death. It was as if by fighting and putting their life on the line, they could redeem their honor and be restored to society. They inspired courage and were even believed to be sex symbols for female spectators.

Some gladiators were able to live long enough to buy their freedom, yet many of those who did decided to return to the arena. Free gladiators were very popular. Those who earned freedom had lots of experience and were expected to put on a good performance. Gladiators who volunteered were considered a novelty. Another special treat were female gladiators. There is considerable debate over when they first appeared and in general there is little information about them.

For all the excitement generated by the gladiators, the Roman authorities nonetheless understood the dangers of this form of entertainment. They would not forget the rebellion of Spartucus in which a Thracian became a gladiator and escaped with fifty or so other gladiators in 73 BCE. Under his command, they fought off several Roman armies successfully for two years, until finally being defeated. Survivors were crucified along the Appian Way, one of the most famous roads leading to Rome.

Following the incident, control over gladiatorial training schools was tightened and discipline was severe; for instance, in Pompeii the prison at gladiatorial barracks was so low that it was only possible to sit or lay down in it. In Rome, there were four training schools and all were run by the imperial court. Independent managers over gladiatorial schools could still be found outside the city, however.

Contrary to the popular belief and movie representations, each match was not fought to the death—in fact, most were not. Fights to the death usually came advertised and had official permission, implying they were not standard fare. Even though the life of a gladiator was dangerous, many lived to retire while others were able to acquire substantial wealth.

For instance, a gladiator named Publius Ostorius fought no less than fifty-one fights, which is comparable to modern day boxers at retirement, such as Mike Tyson, who retired after fifty-eight fights. Training standards were extremely difficult and the general idea behind the match was to conquer the opponent using skill, not necessarily killing them.

This is not to say it was in any way less dangerous, because serious wounding or even death was possible. In training, gladiators were taught to stab rather than slash with a weapon, which was more deadly. Thus, even if the point was not to kill, the possibility of doing so was fairly high. If injured, however, gladiators had access to some of the best doctors in the Roman Empire.

It is important to note that many gladiators were trained for years at the school’s expense. Hence, a good, experienced gladiator was an expensive investment. Gladiators were typically leased. If seriously injured or killed, the leases were converted to sales which were far more expensive, in some cases as high as fifty times the lease price. Since the gladiator could no longer be returned or fight, this was a way for those leasing them out to cover the potential loss of profit.

Gladiators’ worth ranged from 3,000 sesterces to as much as 12,000-15,000. Star gladiators could receive up to 100,000 sesterces, which was an incredibly high figure compared to the annual salary of average Romans. For instance, during the reign of Emperor Augustus, an ordinary soldier’s average income was 256 sesterces, while a senator would receive about 38,000 sesterces.

Thus, it would not make much sense to have them fight to the death. Gladiators usually fought until one signaled defeat or surrendered. In some cases fights ended in a draw, if they were equally matched. Officials known as summa rudis carried long rods (most likely to signal from a safer distance) and oversaw the fight. Many historians think they determined when combat was to be stopped even if the gladiator did not submit, like modern-day referees in the boxing ring.

When the match was over, the summa rudis occasionally let the editor make the final decision; he, in turn, would sometime yield it to the people, letting the crowd make the decision over life and death. In very rare cases, the victors themselves were able to decide the fate.

However, given the immense value of gladiators, matches to the death were not something done on a regular basis, or at least with regular gladiators. There were exemptions, such as people specifically condemned to death through gladiatorial fights. Such a fate might have been assigned to cattle-raiders, for example. They were housed and fed in poor conditions, had little training or armor, and were pitted to fight each other.

It is also worth pointing out that in many cases gladiators did not want to kill or seriously injure another because some of them lived and trained together, and elder gladiators, having more experience and discipline, would coach the younger ones. Those gladiators that did aim at killing the opponent or did not act in the standard behavior were looked down upon by others and in some cases, might have been killed in matches themselves out of revenge.

Gladiators also formed their own unions and had regular meetings. All this speaks to a complex social system beyond a simple recreation of opponents fighting till one or the other was killed, as is often portrayed in cinema.

Gladiators also considered it dishonorable to be opposing an inferior opponent. Thus, they were matched with opponents of similar skill but with different armament type. There were various types of gladiators, for example: murmillones (these wore a large visored helmet, carried a large rectangular shield, and fought with a short stabbing sword), hoplomachs (these wore a visored helmet, fought with a long spear as well as a short dagger or sword, and were protected by a small shield), thraeces (these wore visored helmet with wide brim, carried a short rectangular shield and fought with a short sword whose blade was curved or kinked), or secutores, (these wore an egg-shaped helmet with round eye-holes, carried a large rectangular shield, and a stabbing sword). The crowd especially liked a left-handed gladiator, which is an interesting phenomena. Left-handed boxers are popular to this day and are often very successful, such as Manny Pacquiao.

Gladiatorial fights slowly faded out of Roman life, although it took some time. Emperor Constantine I issued an edict in 326 CE abolishing the fights, however it seems it was generally not enforced. His son, Constantius II, in 357 CE forbade soldiers and officials in Rome from taking part in them personally, and just few years later Valentinian I prohibited Christians from being forcibly sent to gladiatorial schools. Even though the fights persisted for many years later, final abolition seemed in place by 681 CE.

A lot of time has passed since in then. Today, we imagine these ancient warriors and those who cheered them on. We ask how brutal and heartless they must have been. Yet to them, gladiatorial fights provided an escape from everyday life, from their worries and problems.

The same thing drives our own entertainment: MMA fights have been growing in popularity worldwide since the early 1990s, while boxing has come a long way since the bare-knuckle fights of the 18th and 19th centuries. In a mere hundred year span (from 1900 to 2000) 1,358 deaths were recorded directly linked to boxing matches. That is roughly thirteen deaths per year. Other sports, such as football, are also very dangerous, with occasional deaths and concussions now being linked to long-term health problems. Nevertheless, every hit, every knockout is what fascinates us.

Today’s world brings us slow-motion replays, frame-by-frame analysis and a flood of social media clicks – the more shocking and deadly, the more views and coverage. The arena has remained a junction of fame, admiration, danger and death.

In the Roman world, Emperor Augustus and his successors considered gladiator fights a good form of propaganda for unity of the empire. Aren’t American Super Bowl matches an interesting comparison? Does its opening ceremonies, national anthem, military plane flybys, fireworks, and halftime show serve a similar purpose, whether by design or not?

The world has changed a lot since the days of ancient Rome, but our inner urge for adrenaline — whether as a spectator or participant — is not much different from those who lived 2,000 years ago.

References:

Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2015.

Cagniart, Pierre. “The Philosopher and the Gladiator.” The Classical World, Vol. 93, No. 6 (Jul. – Aug., 2000), pp. 607-618.

Carter, Michael J. “Bloodbath: Artemidorus, Αποτομοσ Combat, and Ps.-Quintilian’s “The Gladiator”.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Bd. 193 (2015), pp. 39-52.

Carter, M.J. “Gladiatorial Combat: The Rules of Engagement,” The Classical Journal, Vol. 102, No. 2 (Dec. – Jan., 2006/2007), pp. 97-114.

Concannon, Cavan W. “Not for an Olive Wreath, but Our Lives”: Gladiators, Athletes, and Early Christian Bodies,” Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 133, No. 1 (Spring 2014), pp. 193-214.

Curry, Andrew. “The Gladiator Diet,” Archaeology, Vol. 61, No. 6 (November/December 2008), pp. 28-30.

Grant, Michael. Gladiators: The Bloody Truth. New York: Penguin Books, 1967.

Mathisen, Ralph W. Ancient Mediterranean Civilizations: From Prehistory to 640 CE, 2nd Ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

McCullough, Anna. “Female Gladiators in Imperial Rome: Literary Context and Historical Fact,” The Classical World, Vol. 101, No. 2 (Winter,2008): pp. 197-209.

McManus, Barbara F. “Arena: Gladiatorial Games,” The College of New Rochelle, https://vroma.org/vromans/bmcmanus/arena.html

Meijer, Fik. The Gladiators: History’s Most Deadly Sport. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2005.

Svinth, Joseph R. “Death Under the Spotlight: The Manuel Velazquez Collection, 2011” October 2011.

University of California, “Roman Empire 14 CE, income distribution –GPIH,” https://gpih.ucdavis.edu/files/BLW/Roman_Empire_14.doc

Voiland, Adam. “The Eight-Thousanders,” Dec. 16, 2013, earthobservatory.nasa.gov.

Winks, Robin W. and Susan P. Mattern-Parkes, The Ancient Mediterranean World: From the Stone Age to A.D. 600. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.