Written by Mary Naples, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

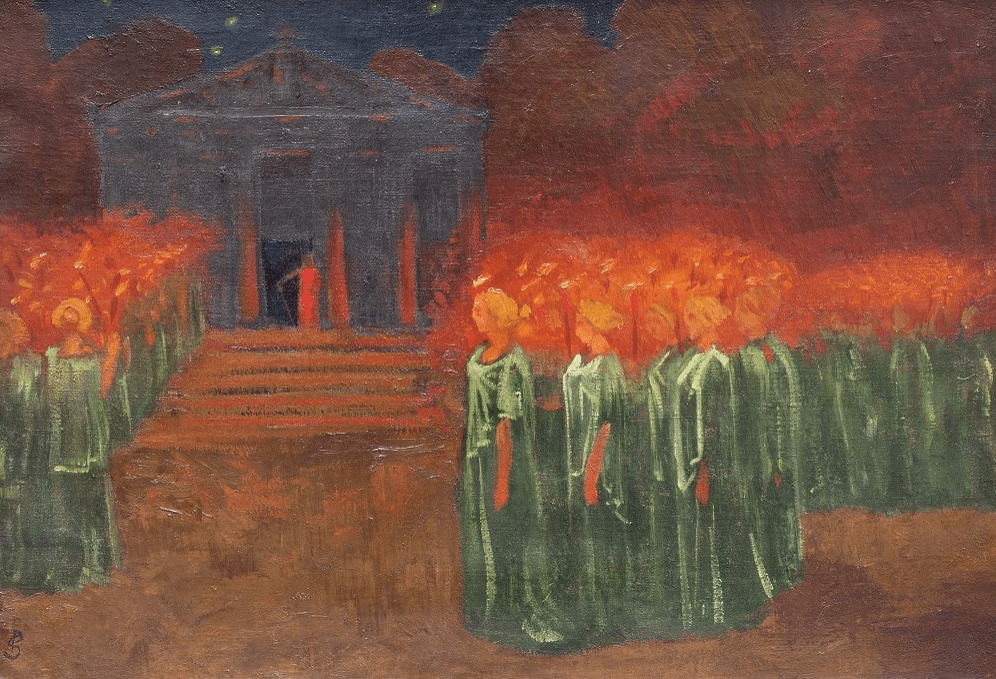

Conjuring up mystical images of secret initiation rites held under cover of darkness, the Eleusinian Mysteries were reputedly a dark and dangerous festival. In fact, the rituals were surrounded by such an aura of deadly secrecy that the tragedian Aeschylus was nearly killed on stage just for referencing them. But what were the Mysteries really about? And what made them so renowned?

Demeter’s Rites of Eleusis—better known as the Eleusinian Mysteries—were egalitarian yet exclusive. Open to everyone free of “blood guilt” (murder) but exclusive to those initiated in their secret rites, this was one of the most acclaimed religious festivals in the Greek world.

Like the all-female festival Thesmophoria, the Mysteries honored Demeter, goddess of the harvest and her daughter, Persephone, queen of the underworld. The Eleusinian Mysteries allegedly emerged as a masculine response to the Thesmophoria. The festival sprang from the myth in which Demeter’s daughter Kore is kidnapped by Hades, lord of the underworld. After her abduction, Kore’s name changes to Persephone.

Carrying a torch, Demeter searches nine days for her daughter and has adventures with mortals along the way until she realizes her true strength lies in her fertility—so she halts the seasons. Earth becomes a barren wasteland. Zeus pleads with Demeter to make the earth abundant once again but she will not relent until Persephone is returned to her. Zeus orders Hades to release Persephone. Hades adheres, but not before luring Persephone into eating a pomegranate seed. The mere act of eating in the underworld binds Persephone to Hades for a few months each year.

The myth is allegorical of agricultural renewal, from life to death and back again each year. Although agriculture played a part in the Mysteries, its role was greatly diminished in favor of the eschatological nature of Demeter’s story; that is to say, issues regarding life after death. In the minds of the ancients, nature’s resurrection each year was emblematic of humankind’s immortality.

Thought to have predated the Greek Dark Ages (1100 BCE-800 BCE), the Mysteries reach back into the Mycenaean period (1600 BCE- 1100 BCE), yet the bulk of evidence about the festival dates from the Archaic period (800 BCE- 480 BCE).

Although its foundations were in the Greek world, it was celebrated throughout the Roman Empire and garnered near-universal reverence up until the late fourth century CE when Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I proscribed worship outside Christianity. But the Eleusinian Mysteries were more than a religious festival. The event had become part of civic identity — its renown in ancient Greece and beyond played a pivotal role in shared cultural hegemony.

What, then, was so mysterious about the Eleusinian Mysteries? The answer can be found in the word itself. Novice initiates of the cult were called mystai and the accompanying ever-secret initiation ritual was called mysteria; participation in the secret cult was restricted to its initiates and initiation ceremonies played a key role in the sacred rituals.

The Eleusinian Mysteries were composed of both the Lesser Mysteries honoring Persephone and were observed in the spring. The Greater Mysteries, honoring Demeter and celebrated six months later, fell in the fall in the month of Boedromion, now known as September-October—directly before the sowing season which heralded the female Thesmophoria.

As a preparation for the Greater Mysteries, a candidate could become a mystes, or novice-initiate, to begin his or her worship in the ranks of the Lesser Mysteries. The mystes would progress into the more enlightened Greater Mysteries once his or her initiation was complete. The initiation period is believed to have been a year, after which time the mystes, orblinded one, would ascend into the hallowed ranks of epoptes, or seer, and be able to participate as a full initiate of the Greater or Epoptical (all-seeing) Mysteries.

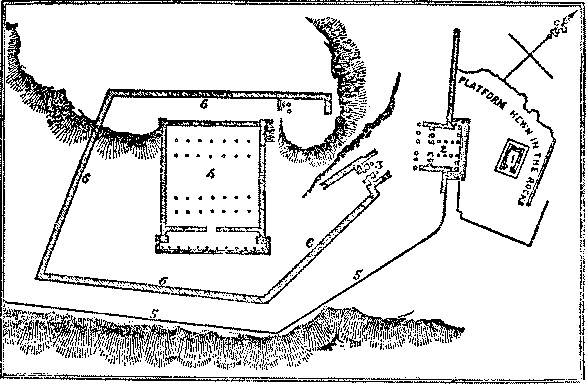

Though the most sacred of the rituals were celebrated in Eleusis—an agricultural town some twelve miles northwest of Athens—people came from all over the Greco-Roman world to Athens to participate in the nine-day event. The procession from Athens to Eleusis was considered the most spectacular of all religious processions in the ancient world. In fact, the road between the two cities (called the Sacred Way) became so legendary that before the Romans arrived, it was the only road in all of central Greece that was not a goat path.

Adherents of the Mysteries came from all over the Greco-Roman world but the rituals were celebrated exclusively in Athens and Eleusis. Until the mid-sixth century BCE, Eleusis controlled the festival but after it was conquered by Athens, the Athenians took over. This made the Mysteries more well-known and transformed the festival from Demeter’s Rites at Eleusis into the celebrated Eleusinian Mysteries.

Technically, membership in the Mysteries was unrestricted. Open to all men and women, slaves and foreigners alike—everyone ”free of the pollution of murder”—could participate, yet in reality there were some restrictions. While foreigners were welcome in the Mysteries, initiates had to speak Greek as “not being a barbarian” was a requirement. This, however, changed when Athens assumed control of the rites. They lifted the Greek speaking requirement in order to promote the Mysteries across the Greek world and beyond. Might they also have lifted the blood guilt ban? Militarism had engulfed the region—soldiers were aplenty and encouraged to join the Mysteries, which they did with abandon. However, despite loosening their standards for some, during the fourth-century BCE, Athens tightened them for others. They began requiring initiates to pay fifteen drachmas for the privilege of membership. Fifteen drachmas was equivalent to ten days of labor—an amount that the poor or enslaved would likely have been unable to pay.

While the rituals were initially concerned with Demeter’s imparting gifts of fertility and the cyclical nature of creation, over time they focused more on immortality. Of the Mysteries, the poet Pindar (498 BCE – 436 BCE) opined: “Blessed is he who has beheld the mysteries, descending in the Netherworld. He knows the aim; he knows the origin of life.” To be sure, the main focus of the Mysteries was the happy afterlife initiates were promised.

In discussing the difference in focus between the all-female Thesmophoria and the Eleusinian Mysteries, classicist Marcia D. S. Dobson contends that the difference between the two cults could be based on gender, as women are closer to nature and therefore more accepting of death. She contends: “Because the male connection to the natural rhythms of life and death are not as immediate, a man experiences his mortality as a devastation of his individuality.” Rebelling against nature, men are at odds with the cyclical patterns of regeneration that the two goddesses represent; the assurance of a happy afterlife helps them overcome this dissonance. But are women any less interested in the notion of a happy afterlife than men?

It was during the Archaic era— when the Mysteries were in full swing— that the attitude toward death and afterlife began to shift in the Greek world. Prior to this era, death was viewed as part of the natural order of things and gloomily accepted. Over the course of time, however, as people began disconnecting themselves from the cyclical patterns of nature, death became more personal and a greater anxiety about it ensued.

Discussing changing attitudes toward death, scholar Christiane Sourvinous-Inwood, a leading voice on the Hellenic world, argues: “There was a shift in the attitudes in the Archaic period, from an acceptance of a familiar (hateful but not frightening) death, to the appearance of attitudes of greater anxiety and a more individual perception of one’s death, conducive to the creation of eschatologies involving a happy afterlife.”

Alas, the Elysian Fields awaited only those infrequent few who were bestowed with immortality by the gods. To be sure, until the Mysteries began to gain a foothold, afterlife for the ancient Greeks was a cheerless proposition. Regardless of achievements and position in life, kings and slaves alike could expect to spend eternity fluttering around endlessly in a shadowy underworld.

Even Achilles, war-hero great and demigod in life, was reduced to an insubstantial shade in dusty death: “No winning words about death to me, shining Odysseus! By god, I’d rather slave on earth for another man–Some dirt-poor tenant farmer who scrapes to keep alive—than rule down here over all the breathless dead.”

After all, if such a dismal destiny awaited a near god, what chance did an average bloke have? At the end of the day, faced with the prospect of a happy afterlife, is it any wonder that the ancients were lining up in droves to become initiates in the Eleusinian Mysteries?

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.