Written by Mary Naples, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

In Jason and the Argonauts, Medea—another goddess-cum-princess from a foreign land (Colchis, present-day Georgia)—also acts against her better interests by abandoning her royal family for the Greek hero, Jason, who ultimately deserts her. To seize the Golden Fleece, Medea helps Jason every step of the way, even at the expense of her father and the murder of her brother.

Although their stories differ in substance, both Ariadne and Medea share exploitation as a recurrent theme when they are cast aside after wearing out their usefulness to the hegemonic Greek heroes (see: Aspects of Ariadne, Part 1).

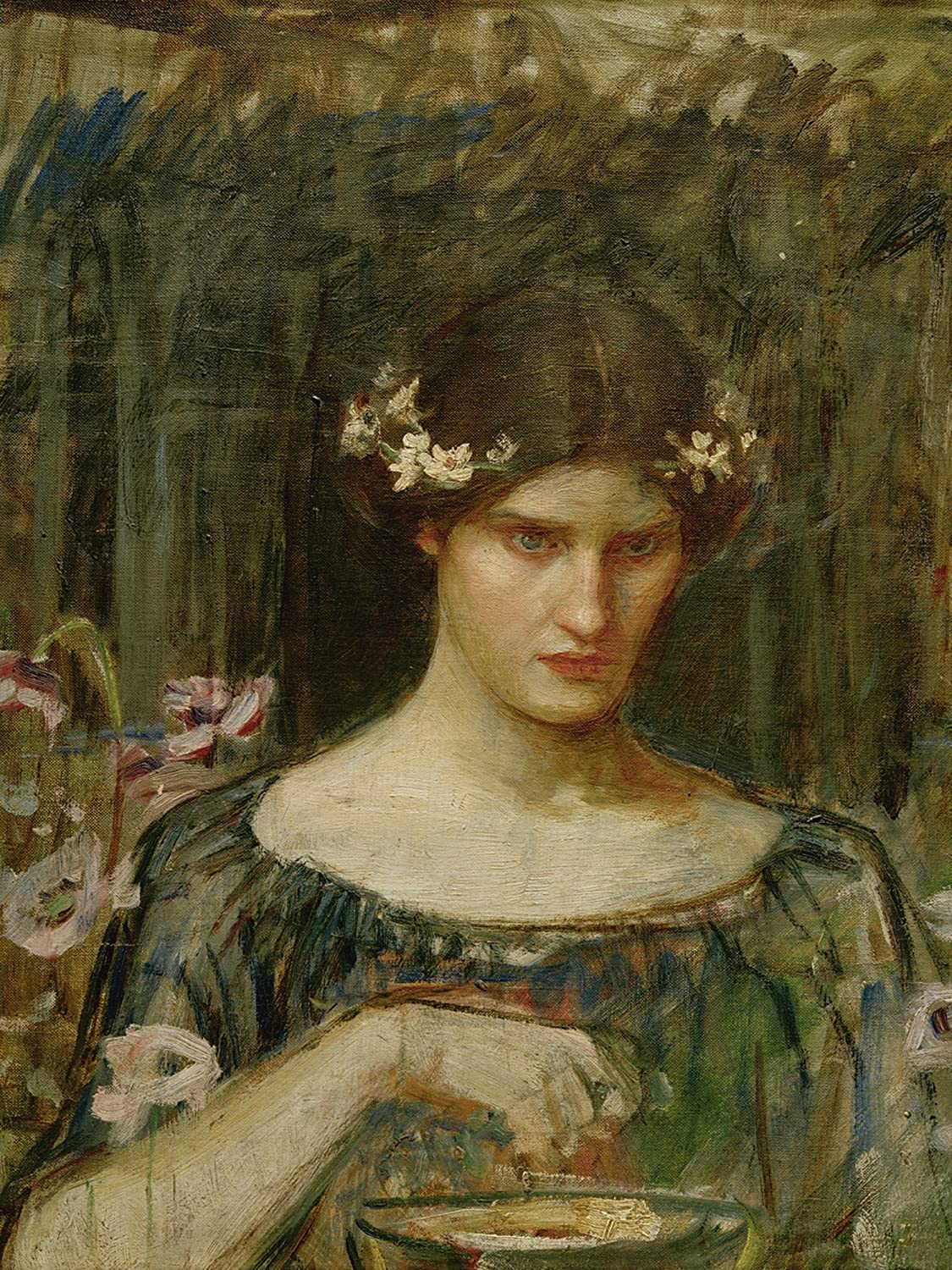

John William Waterhouse, “Sketch for Medea”, oil on canvas, 1906-1907. Stephen and Linda Waterhouse private collection

Demonstrating the lack of parity between the Greeks and their conquests, the women—often considered part of the spoils of war—represent the subjugated from vanquished lands, while Theseus and Jason play the roles of heedless invaders—symbolic of the colonizing Mycenaean Greeks—plundering the resources of the defeated while fleeing with its most valuable possessions.

Being vanquished, however, is not the only similarity of the two women.

Unlike her counterpart from Colchis, Ariadne is not known for vengeance, yet in a surviving passage attributed to the scorned Ariadne from Euripides’ Theseus is the line: “and yet I will tell a tale worthy of blame…”

Hellenistic poet, Catullus (84 BCE-54 BCE) expands on this theme in his epic Poem 64, where taking a page from Medea, Ariadne calls for vengeance against her Greek hero. Before he had left for Crete, Theseus had promised his father that if his mission were a success he would hoist a white sail in place of the black sail which in previous years symbolized the sacrificed fourteen Athenian youth.

On account of Ariadne’s curse, when Theseus leaves the distraught princess, he forgets to hoist the white sail. Upon sight of the black sail, Aegeus—believing his son dead—jumps to his death into the sea, which henceforth would be named in his honor: the Aegean.

Just as the gods in Euripides’ Medea aid Medea in her quest for revenge, so Catullus tells of how Jupiter comes to Ariadne’s defense.

Yet Ariadne is not good at vengeance. When Medea had revenge on Jason, she destroyed his bride, his progeny and his future, whereas Ariadne’s act of vengeance would make Theseus king of Athens.

Along with the similarities between the two scorned women, as granddaughters of the Sun god, Helios, both women possess supernatural powers and as such represent vanquished deities, as well. Some suggest Medea also may have been a pre-patriarchal goddess.

In his seminal book The Masks of God: The Occidental Mythology Joseph Campbell asserts: “It consists simply in terming the gods of other people demons, enlarging one’s own counterparts to hegemony over the universe, and then inventing all sorts of great and little secondary myths…to validate not only a new social order but also a new psychology.”

At its heart, the Myth of the Minotaur is about a Cretan monster more bull-like than human who devours Athenian young. Not lost is the fact that bulls in Minoan Crete were not only objects of veneration but quite possibly used in their sanctified rituals as well. Yet denigrating a sacred animal was only part of their discrediting.

More powerful still was their marginalization of Ariadne by transforming the Minoan great mother goddess into a lovesick maiden who is subservient to the Greek hero, Theseus. Reduced to a mere conduit for Theseus’s success, the truth is if not for the help of Ariadne, Theseus would be a mere postscript—neither king nor hero. Yet Theseus is the star of this story—Ariadne only a bit player.

After renouncing her family and homeland Theseus abandons her—while she is sleeping—leaving her for dead on the alien and desolate island. In some versions, a heartbroken Ariadne commits suicide.

At this point the reveler and bon vivant, Dionysus—god of the grape harvest—enters the stage. According to one tradition, Theseus was compelled to leave Ariadne because of threats made by the god Dionysus, who wanted Ariadne for his own. Left with little in the way of choice, Ariadne acquiesces.

Put another way, a sleeping Ariadne resembles an unaware Persephone picking flowers while whisked away by the lord of the underworld—her own Uncle Hades—to wed in the abyss. Seen this way, marriage is a violation, which is precisely how the historian Pausanias (115 CE-180 CE) expresses the marriage of Dionysus and Ariadne: “Ariadne asleep, Theseus putting to sea and Dionysus arriving to rape Ariadne.”

Here Ariadne is like all Greek girls, whose marriages—arranged by their fathers to total strangers typically twice or three times their age—must have felt like a sort of rape. Thought to have originated in Thrace or Asia Minor, Dionysus is a foreign deity believed to have been amongst one of the older chthonic (subterranean) gods known for their roles in fertility.

Ariadne, no longer a Minoan princess, is once again a fertility goddess whose sleeping—suggestive of the period where the earth lies dormant—is analogous to Persephone going underground for a few months each year.

Unlike the love story between the Greek hero and his love-struck aid, the union between Ariadne and Dionysus resolves itself each year. Moreover, Dionysus bestows Ariadne with a gift from the gods: a gold crown, formerly Aphrodite’s—forged by Hephaestus—with red gems shaped like roses would eventually be placed among the stars, becoming Corona Borealis (Crown of Lights) in the night sky.

But there is a twist to the story. In Homer’s Odyssey, Artemis—the virgin goddess of the hunt and of chastity, renowned for brutally punishing wayward women—slays a mortal Ariadne for her infidelity to Dionysus who was, evidently, her husband all-along.

From the Odyssey the phrase is interpreted as “on the denunciation of Dionysus.” Apparently, Dionysus was upset because Ariadne defiled his grotto by her love for Theseus. Never mind that Dionysus himself was a notorious seducer.

Patriarchal to its core, the Odyssey—perhaps originally composed in the oral tradition as early as the Greek Dark Ages (between 1200-850 BCE)—is at heart a story about Odysseus’ adventures and numerous infidelities in his ten-year long homecoming while at home. pining for him, his wife—Penelope—is content to stitch away the years.

Ariadne’s infidelity, however, can be explained in the context of fertility and occurs during the infertile time of the year, when the fertility god’s seed lies dormant. At that point the fertility couple separates, and the goddess goes away—perhaps harkening back to an era before marriage when women had more agency in their reproductive lives. Finally, Ariadne either sleeps or dies during the dormant season. After all, for a fertility goddess, sleeping and dying are much the same thing.

End of Part 2

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.