A lone figure, swaddled in rags sits secluded in a dank cave bent over his papyrus. The whittled reed in his hand dips rhythmically into the pot of octopus ink before adding a couple of urgent scratches to the thick page. His bushy, white beard is stained off-centre at the lower-lip, evidence of his habitual pen-chewing; but it is his mind, his mind that is stained far more indelibly. There are images of gods, war, warriors, adultery, incest, exile, blasphemy, damnation, infanticide, patricide, matricide, human-sacrifice, and worst of all, foreigners. These are the ideas, the dark and evil components of Greek tragedy, that this man, this Euripides believes are too… too… stock, too trite, too bedtime-story for the citizens of Athens. He knows that beauty is terror. “Whatever we call beautiful, we quiver before it.” (Donna Tartt)

A lone figure, swaddled in rags sits secluded in a dank cave bent over his papyrus. The whittled reed in his hand dips rhythmically into the pot of octopus ink before adding a couple of urgent scratches to the thick page. His bushy, white beard is stained off-centre at the lower-lip, evidence of his habitual pen-chewing; but it is his mind, his mind that is stained far more indelibly. There are images of gods, war, warriors, adultery, incest, exile, blasphemy, damnation, infanticide, patricide, matricide, human-sacrifice, and worst of all, foreigners. These are the ideas, the dark and evil components of Greek tragedy, that this man, this Euripides believes are too… too… stock, too trite, too bedtime-story for the citizens of Athens. He knows that beauty is terror. “Whatever we call beautiful, we quiver before it.” (Donna Tartt)Well… No. I’m afraid not. At least, we’ve no reason to believe that the man who produced, directed and wrote The Bacchae, Hippolytus, Medea, and Electra really was the tortured recluse, the artistic oddball, the Salinger or Kubrick of his day. We like to think this because, instead of merely putting a new spin on traditional Greek myths, he always managed to find an even more shocking way to deliver a tried and trusted tale. He could make heroes devils and devils heroes and all without forcing the audience to break their mental stride.

Electra at the Tomb of Agamemnon by

Frederic Leighton, 1st Baron Leighton

Yes, he may well have lived in a cave on the island of Salamis, but what better place for a writer to escape the distracting hustle and bustle of Athenian city existence?

Likewise, late in life, Euripides left Athens for Macedon in self-imposed exile. Was he frustrated at a theatre-going public who didn’t appreciate him? Or was it, more likely, a lucrative retirement where his talents were rewarded not only with money, but also with praise and status?

The Death of Hippolytus, by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912).

After all it was these, praise and status, that seem to have alluded Euripides during his lifetime. Despite being considered by many today as the finest of the three great Athenian playwrights (besting Aeschylus for style and Sophocles for substance), he only won the first prize at the city’s premier dramatic contest, the Great Dionysia, four times during his lifetime and once posthumously.

You may be thinking ‘that’s not so bad – nobody ever won more than four Academy Awards for best director’, but if you compare his record to that of Aeschylus (13 wins) and Sophocles (20+), it seems a paltry return for a man of such insight, intensity and timeless genius.

Don’t think however, that this modest return of gongs equated to a shortage of fame. A contemporary playwright, the comedian Aristophanes, made sure everyone in Athens, even those uninterested in tragedy, knew all about Euripides.

Aristophanes, along with other exponents of Old Comedy, used rumours about Euripides as material to create a comic alter-ego who was not merely joked about, but lampooned directly whilst appearing as a character in several plays.

Common jokes were:

- That Euripides’ wife was having an affair with his lodger, who also happened to collaborate with Euripides in writing some of his plays.

- That this cuckolding created in him such bitterness that many of his plays ended up propounding a theme of misogyny.

- That he was an atheist and blasphemous towards the Greek gods.

- That he was responsible for making tragedy less lofty e.g. whilst Aeschylus uses kings, gods and heroes as characters, Euripides uses beggars, cripples and the working-classes. And even when portraying kings they are clad in rags and slovenly.

- That his mother sold cabbages in the agora – an early example of a “yo momma” joke i.e. “yo momma so poor, she sells cabbages in the agora”.

- That he, like his contemporary Socrates, subverted the moral order of the day.

It is worth remembering that Aristophanes, like all comedians, was more concerned with laughs than with truth. Indeed, it is almost impossible to imagine that Euripides was from anything other than a high-class family and enjoyed a fine education.

Whether or not his wife was playing away, we do not know for sure, but anybody who closely studies his plays would find it hard to conclude he was a misogynist. In fact, even more than his great rivals, Euripides treats his female characters with great sensitivity and sympathy, as well as portraying them as independent and intelligent.

Jason and Medea – as depicted by John William Waterhouse, 1907

Moreover, it is quite likely that Euripides would have actually been in the audience when some of these zingers landed, making the impact of the joke two-fold. First, as the audience appreciated what the actor said, then second, as the audience turned as one to the embarrassed, angry, or perhaps, laughing Euripides – much like President Obama’s roast of Donald Trump at the Whitehouse in 2011.

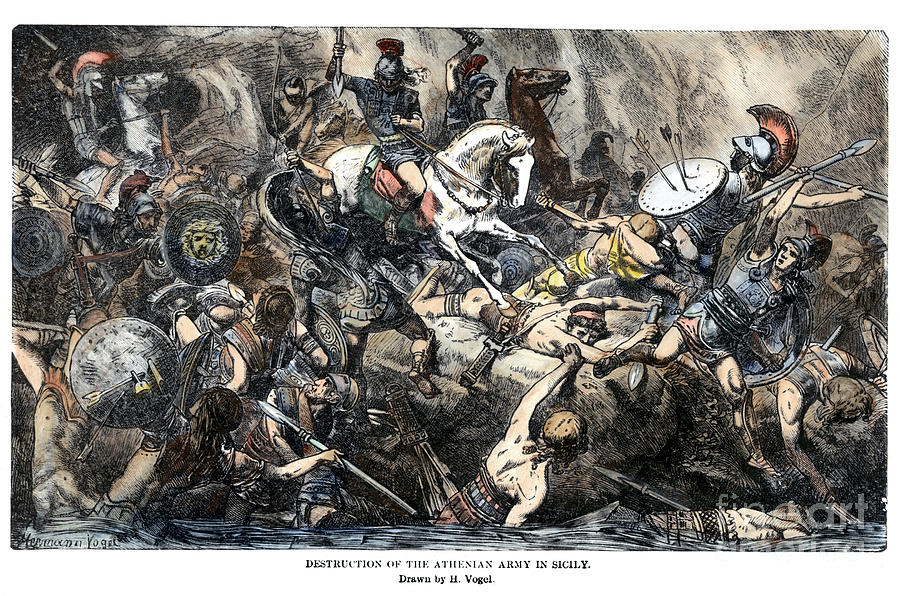

One area where Aristophanes did not poke fun at Euripides was that of peace and war. The 5th century BC was a time of relentless fighting for Athens and both men used their art as a medium to criticise either politicians or the very nature of war itself. Indeed, it’s possible one reason Euripides was not a man appreciated in his own time was because of his unwillingness to slap a ‘support our troops’ sticker on the front of his programmes.

Peloponnesian War, where Athens suffered tragic defeat

Whilst accusations he was a pacifist were perhaps a little wide of the mark, both he, and Aristophanes, stood out as men who used their talents to campaign against the involvement of Athens in expensive, devastating and pointless military campaigns.

Much as Euripides’ attempts to win favour with the public were to no avail, his efforts to influence popular opinion on foreign policy matters were equally fruitless. Two years after his death, Athens fell to the Spartans.

The cradle of democracy never recovered its status as the leading light of Western civilization.

Euripides’ legacy is a theatrical, not a political one. He changed theatre from a vehicle for education and moralizing to one of doubt and introspection. Whilst it is his complexities, his ambiguities and his lack of conformity that brought him up against such resistance in his own time, it is perhaps those same qualities that keep him relevant and endear him to so many today.

“Euripides Greek Tragedy’s Unsung Hero” was written by Ben Potter

2 comments

Well done Ben Potter. Thank you for an enjoyable article!

Aristotle probably caught it best, when he described Euripides as “the most tragic of all the playwrights”. I like to think that Aristotle appreciated Euripides work in a way that his fellow Athenians did not–and understood the true tragedy of his career was that he was not recognized in his own time for the psychological depth of his works. But we probably owe the Roman poet/politician Seneca (1st century CE) our greatest debt of gratitude; had Seneca not been so devoted to Euripides, it is likely that even more of the latter’s works would have been lost to us forever. As it stands, we have more complete works by Euripides than by any of the other dramaturgs of the 5th Century. Euripides, it should be noted too, has provided us with the only extant example(s) of a satyr play in ‘The Cyclops’ (and perhaps ‘Alcestis’). Anyway–all that aside–thanks again to Ben Potter! Well done!

Thanks for sharing!

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.