Written by Katherine Smyth, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Parthian Attacks

With barely enough time to get comfortable in the Emperor’s seat, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus’ minds were turned to a ghost that haunted their predecessor. As Emperor Antoninus Pius lay dying, his mind was often consumed by the actions of foreign kings. Such worries would turn out to not be unfounded, though Antoninus would (perhaps fortunately) not live long enough to see his fears justified.

In late summer or early autumn of 161,

Vologases IV of Parthia invaded Armenia, removing and exiling its king before installing a king of his choosing, King Pacorus. The governor at the time, Marcus Sedatius Severianus, an experienced military man and Gaul, was, unfortunately, mislead by the prophet Alexander of Abonutichus.

It was the prophet who told the governor that he would easily defeat the Parthians and win glory for himself in the act. Severianus was duped by the snake handler and lulled into a false sense of military superiority.

Coin (front and back) of Vologases IV, minted at Seleucia in 156.

Sadly, Severianus led a legion into Armenia to challenge the Parthians. But, the Parthian general Chosrhoes trapped him near the head of the Euphrates River, at Elegia. Severianus attempted several engagements with the general but failed each time. After three days he committed suicide, leaving his legion to be massacred by the Parthians.

In the winter of 161-162, it was decided that Lucius would take over and direct the Parthian war. As he was strong and healthy, this seemed a wise choice, rather than sending Marcus who had always suffered from bouts of illness.

Marcus may have had an ulterior motive for sending Lucius; as the lesser emperor had developed a taste for debauchery, and he hoped the terror of war would straighten him out and remind him that he, too, was an emperor.

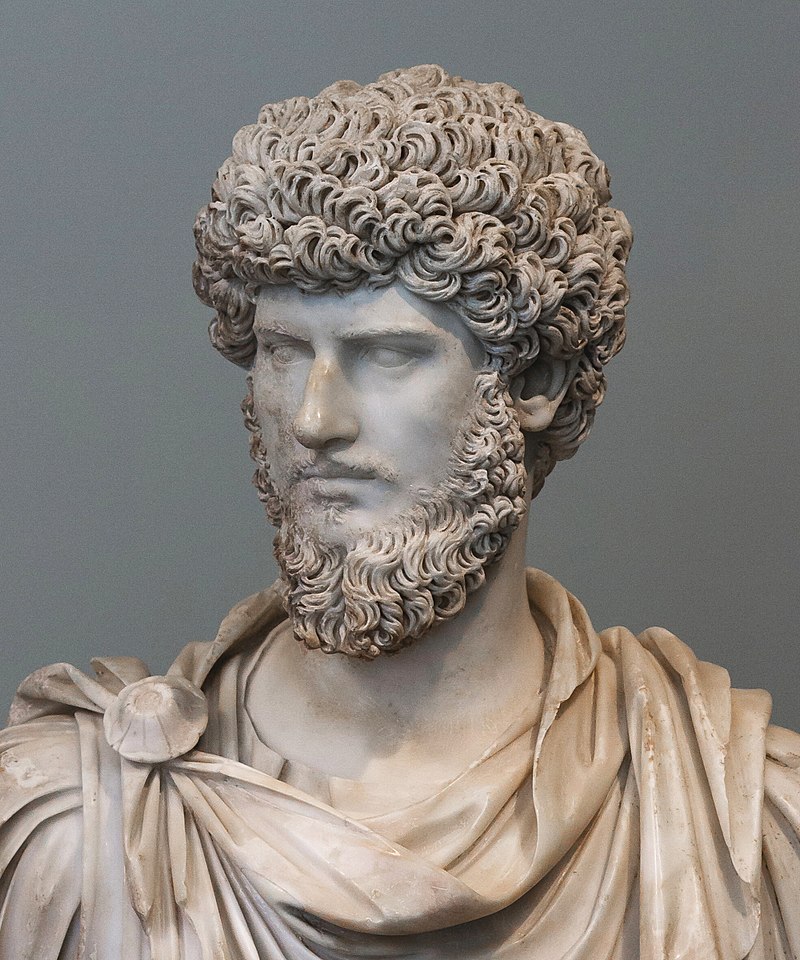

Marble portrait of the co-emperor Lucius Verus, Roman Antonine period.

Thus, in the summer of 162, with the senate’s blessing, Lucius left for the Parthian war. He would spend much of his time in Antioch, wintering at Laodicea, and spending the summers at Daphne, enjoying what were to be his final days as a bachelor. In the autumn of 163, or early 164, Lucius married Lucilla in Ephesus after Marcus moved up the marriage date; perhaps as a result of Lucius taking a mistress, Panthea.

Marcus did not attend the marriage of his 13year-old daughter. Instead, he accompanied them as far as Brundisium, and returned immediately to Rome after they boarded the ship. Some evidence suggests that he was not entirely happy with the arrangement, as he also sent word to his proconsuls not to give the company any official reception.

In the coming years, the war with the Parthians would continue back and forth, with both sides sustaining bitter defeats with heavy losses. Eventually, in 165, the Roman forces moved on Mesopotamia, and after a series of skirmishes the Parthian army was routed at the Tigris River, before the Roman army continued on down the Euphrates River for another major victory. Lucius and the Roman army then turned their sights on the cities of Ctesiphon and Seleucia.

Where Ctesiphon occupied the left bank of the Tigris, Seleucia sat on the left, and despite offering no resistance to the invading army, Seleucia was ransacked. At the end of 165 Ctesiphon was seized, and as the only city that had withstood the Romans, it then faced having the royal palace raised to the ground by fire. Both of these pillaging conquests would leave a black mark on Lucius’ honor and reputation.

Busts of the co-emperors Marcus Aurelius (left) and Lucius Verus (right), British Museum.

Upon the army’s return to Rome, Lucius adopted the title Parthicus Maximus, and both he and Marcus were hailed as imperatores again. When the army returned, in 166, to Media, Lucius then added the extra title Medicus to his name, while Marcus chose to wait until then to include Parthicus Maximus to his list of honors. The two emperors were then hailed as imperatores for the fourth time, and on 12th October Marcus announced his two sons as his heirs-apparent; Annius and Commodus.

Rebellion On All Fronts

The Parthian War wasn’t the only military matter that occupied Marcus’ thoughts. Indeed, much of the 160s were consumed with attacks on almost all of the Roman Empire’s borders. There were skirmishes in Britain, in Raetia (eastern and central Switzerland), and Upper Germany. Marcus had been ill-prepared for inheriting such a calamitous state, and with very little military experience, he was guided by others.

In 166 the borders of the Roman Empire were broken in Upper Germany by the indigenous tribes of the area. Unfortunately, Marcus had replaced capable leaders and governors with friends and relatives of the imperial family, and this nepotism would come back to haunt him.

Where the Roman army had so far succeeded in repulsing the advances of smaller bands of the Germanic tribes, in 168 they faced a much more dangerous combination of united tribes who crossed the Danube.

The Course of Empire (series of paintings by Thomas Cole): The Consummation of Empire (1836).

At the same time, the Costoboci from Carpathia invaded Macedonia and Greece. However, Marcus was able to repel this attack for the moment. While fending off this advance, the Germanic tribes began settling in Dacia, Pannonia, Germany, as well as Italy.

Although this was not unheard of, the sheer numbers of tribes relocating there required the creation of new provinces; and with the overwhelming number of barbarians arriving, it caused Marcus to banish any and all barbarians who’d been brought to Italy previously, for fear of being overrun.

This onslaught of attacks would not be the worst thing Marcus would have to deal with. While returning to Rome, Lucius became grievously ill with the symptoms of gastroenteritis, although some scholars believe it may have been the Antonine Plague, aka; smallpox. Just three days later, he was dead.

The apotheosis of Lucius Verus, 2nd century relief plates from Ephesus, on display at Humboldt University of Berlin

The death of his adoptive brother, and the husband of his 21year-old daughter, caused Marcus a great deal of heartbreak. He escorted Lucius’ body back to Rome. The co-Emperor would be deified and then worshipped as Divus Verus, soon after the funeral games held in his honor.

Lawmaker and Administrator

Marcus proved to be a prudent ruler of the Empire. Now, as the only ruler, he would spend much of his time in Rome, addressing matters of law. There he would decide over disputes and listen to petitions. This is something that his predecessors had failed to do: being competent in navigating imperial administration. He also paid particular attention to the release of slaves, the welfare of orphans, and how city councilors were selected.

He was a shrewd businessman, seeking the senate’s approval before spending money, even though he did not need to do so as Emperor. During this period,

Marcus potentially made contact with Han China, though this tenuous link is via a Roman traveler who claimed to represent the ruler of Daqin. There is physical evidence to support this story, with Roman glassware being found at Huangzhou, which shares some coastline on the South China Sea, and golden Roman medallions have been found at Óc Eo, in Vietnam, which dates to Marcus’ rule, or possibly earlier to Antoninus’.

At any rate, in 165/166 the Antonine Plague broke out in Mesopotamia, and possibly continued long after Marcus’ time as Emperor. The Antonine Plague is now suspected to have been smallpox, and was one of the plagues that afflicted the Han Empire at the time of Marcus’ potential contact.

Rome, Italy. Piazza del Campidoglio, with copy of equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius. The original is displayed in the Capitoline Museum.

It is believed that during this contact, Roman subjects may have begun a new era of Roman-Far East trading. However, this exchange of goods may also have instigated the wider spreading of the plague, and caused severe damage to Roman maritime trade in the Indian Ocean. For instance, archaeological records spanning Egypt to India show decreased traffic, and this had a significant effect on goods going to Southeast Asia at this point.

End of Days

It was a time of upheaval and uncertainty, with heathen tribes surrounding the borders of Rome, and the Antonine Plague ravaging the Roman populous. For much of the 170s, Marcus’ rule was spent attempting to stem the onslaught, and in 177 he named Commodus as co-ruler (his other son, Annius, died in 169).

This decision caused quite a stir, as his appointment was only the second time in Roman history where an Emperor nominated his biological son as co-ruler, the first being Vespasian and his son Titus. Perhaps Marcus hoped for a similar legacy for his family.

Whatever his intentions, Marcus would not live to see them bear fruit. He passed away in 180, of natural causes, in Vindobona—modern-day Vienna. He was 58years old, and his ashes were returned to Rome, and there placed in the mausoleum of Hadrian. Upon his death, he was immediately deified, and

eventually his efforts against the German tribes and the Sarmatians were acknowledged with a column and a temple in Rome.

Detail of a relief scene on the Column of Marcus Aurelius (in Rome, Italy), depicting a battle of the Marcomannic Wars, late 2nd century AD

Conclusion

Despite the tumultuous events that afflicted Rome throughout Marcus’ reign, he is remembered today as the last emperor of the Pax Romana—the golden age of Rome.

Much of Marcus Aurelius’ life was marred by illness, loss of loved ones. Because of his stoic desire to live a quiet life he never sought the limelight of leadership, but when faced with ruling the empire, it was this same stoic attitude of his that allowed him to accept his fate. It was his natural duty, and he abided by it.

Marcus’ choice of an heir has been heavily criticized, as Commodus proved to be erratic, and lacked both military and political savvy. Though Marcus had done his best to raise the boy to be a capable man and future leader, Commodus would be a bitter disappointment to his father.

The death of Marcus and the reign of Commodus would come to mark the end of the Pax Romana. As Cassius Dio wrote, in an encomium to Marcus Aurelius, reflecting on the transition to Commodus and to Dio’s own times, “…our history now descends from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust, as affairs did for the Romans of that day.”

The Course of Empire (series of paintings by Thomas Cole): Destruction (1836).

However, if nothing else, it’s worth remembering Marcus’s steadfastness. As Dio also said of the man he knew,

“[Marcus] did not meet with the good fortune that he deserved, for he was not strong in body and was involved in a multitude of troubles throughout practically his entire reign. But for my part, I admire him all the more for this very reason, that amid unusual and extraordinary difficulties he both survived himself and preserved the empire.”

Marcus’ iconic stoicism, philosophic nature, and compassionate heart meant he constantly worked towards creating a better Roman world. Marcus lived a life of constant challenges, overcoming them where possible, accepting those that he could not, and all the while striving for the betterment of all.

As he once so beautifully wrote in his Meditations,

“Upon every action that thou art about, put this question to thyself; How will this when it is done agree with me? Shall I have no occasion to repent of it? Yet a very little while and I am dead and gone; and all things are at end. What then do I care for more than this, that my present action whatsoever it be, may be the proper action of one that is reasonable; whose end is, the common good; who in all things is ruled and governed by the same law of right and reason, by which God Himself is.” ~ Book 8. II.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.