Eannatum was the King of

Lagash, a fertile town nestled between the

Tigris and the

Euphrates. While his domain was prosperous, Eannatum wanted more.

This ambitious king, upon receiving his power, understood that Lagash’s security relied on its water supply from the

Shatt al-Gharraf. Unfortunately his neighbor, the city-state of Umma, also bordered this very important channel on the western bank. The chief cause of hostility between these important cities is unknown according to some historians, and while we can never be certain, it seems obvious to us that the conflict was over water.

Umma held this one strategic advantage over Lagash. Cutting the water supply to the city would hinder its domestic produce and trade via waterway, effectively crippling commerce in Lagash and sending prices upward on all commodities.

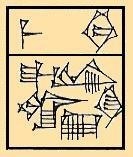

The Enmetena Cone, in the Louvre Museum. Photograph courtesy of Trevor Eccles

Knowing all this then, it might not be surprising that conflict between Lagash and Umma was common. We even have primary sources citing the fact. Enmetena, son of Eannatum II and nephew of the famed conqueror Eannatum I, recorded the history of the battles on a large rock known as the “

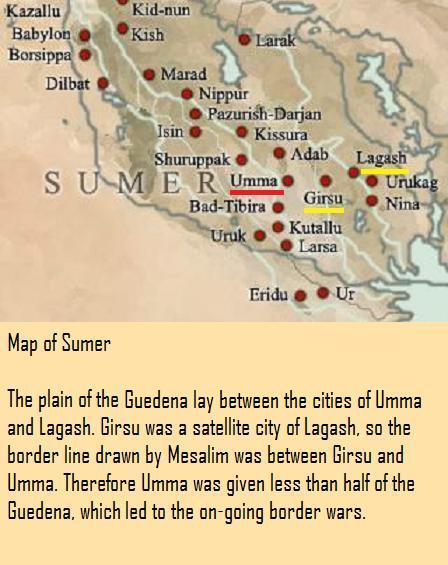

Enmetena Cone.” The engraving describes the first war between the two powers, fighting for possession for the fertile fields of Guedena, located between the two great city-states.

But who decided the border between Lagash and Umma? King or God… or both?

It was, according to our historical cone,

Enlil, who was considered the king of all the lands and father of all the gods. While

Mesalim, king of

Kish, confirmed the decision by placing a mark and a stele on the borderline.

The actual script reads:

Actual engraving

“Enlil, king of all the lands, father of all the gods,

by his righteous command, for Ningirsu and Shara,

demarcated the (border) ground.

Mesalim, king of Kish, by the command of Ishtaran,

laid the measuring line upon it, and on that place he erected a stele.”

This inscription is an entanglement of religion and the state. Enlil was the main Sumerian god. Therefore, he was the judge, jury, and executioner. Enlil was the god who fixed the boundaries and terrestrial estates of the lesser gods. His will could not be changed and his decisions final, regardless of divine assembly.

However, each city-state had a patron god. The god Ningirsu represented the city of Lagash, while Umma worshipped the god Shara.

Lagash made the argument that the borders were already set in place and Enlil was in favor of them retaining control over

Guedena, our attractive fertile field. Umma saw things differently. A mediator, therefore, was needed to settle the dispute. That mediator would be none other than Mesalim, king of Kish, our second name on the historical cone.

The title “King of Kish” actually means “King of the world or King of Kings.” Mesalim was the supreme overseer of the Sumerian lands, which was the civilized world to these people. Mesalim’s decision was final… regardless of the moral argument.

What did this super King conclude? His ultimate directive was to build a trench, along with a levee, on either side to separate the two territories. Finally, the stele was erected at the border indicating his decision. Mesalim’s ruling, however, favored Lagash more so than Umma when it came to the water rights and the fertile fields of the Guedena.

The reason for this decision is unfortunately unknown. Of course we can never be sure, but could it be possible that Lagash was more powerful than Umma?

According to Mesalim, Enlil, the father of the gods, favored the stronger of the two city-states. However, all deities aside, Mesalim likely chose Lagash because it had a much stronger economy and military and could provide more to the loosely knit confederation of the Sumerian city-states in a time of crisis than Umma.

Therefore, in essence, the King of Kish picked the winners and losers of Sumer.

a Sumerian battle scene by HongNian Zhang

This was not the end of the border dispute between the two city-states. Later, Ush, ruler of Umma, marched to the border, smashed Mesalim’s stele, and advanced into Lagash territory. Ush proceeded with his forces to seize the fertile fields of Guedena.

Ush was later defeated from any further advance by an unknown Lagash king.

The Sumerian inscriptions state that, “Ningirsu, the hero of Enlil, by his just command, made war upon Umma. At the command of Enlil, his great net ensnared them. He erected their burial mound on the plain in that place.”

Rather than to the unknown king, the victory was granted to the patron god of the city of Lagash.

The reason there is no mention of the Lagash king is that Enmetena, the great-grandson of

Ur-Nanshe, wrote the story. Ur-Nashe was the founder of the dynasty from which Enmetena came. The man who defeated Ush has to be none other than

Lugal-sha-engur, the predecessor of King Ur-Nanshe.

So why would Enmetena not mention Lugal-sha-engur’s victory over Ush? Simple… Enmetena was not interested in giving thanks or glory to a dynasty that was not his own.

Check back Next week to see how Eannatum takes over the Sumerian valley and creates the first empire!

Read Part One: Lagash and the Too Fertile Valley Here: https://classicalwisdom.com/lagash/

—

“A War for Water – The tale of two City-States” was written by Cam Rea