Written by Ed Whalen, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

We think of Graeco-Roman world as a fairly rational, even secular. However, classical societies were extremely superstitious. In the ancient world, people used religion and magic to help them to cope with what, for them, could be an unpredictable and brutal world.

This led to the rise of not only many religious sects, but also charlatans and impostors.

One of the most notorious of these was Alexander of Abonoteichus. According to one source, he was a false prophet who founded a religion that was enormously influential in the Roman Empire.

Alexander of Abonoteichus

Our main source for Alexander of Abonoteichus is the writer Lucian, a Greek from what is now Syria. However, there are many cultural artifacts, such as coins, that prove that he was a historical figure. Lucian’s account of Alexander is very hostile, and this has colored our perception of him.

Born before 150 ADS in Abonoteichus, a Greek settlement on the Black Sea coast of Asia Minor, Alexander may have been a disciple of the prophet and philosopher Apollonius of Tyana. At some point, he joined a traveling medicine shows that preyed upon the gullible, and during this time he acquired his skills. Alexander was not an ordinary conman—he had ambitions.

The Rise of a Fraud

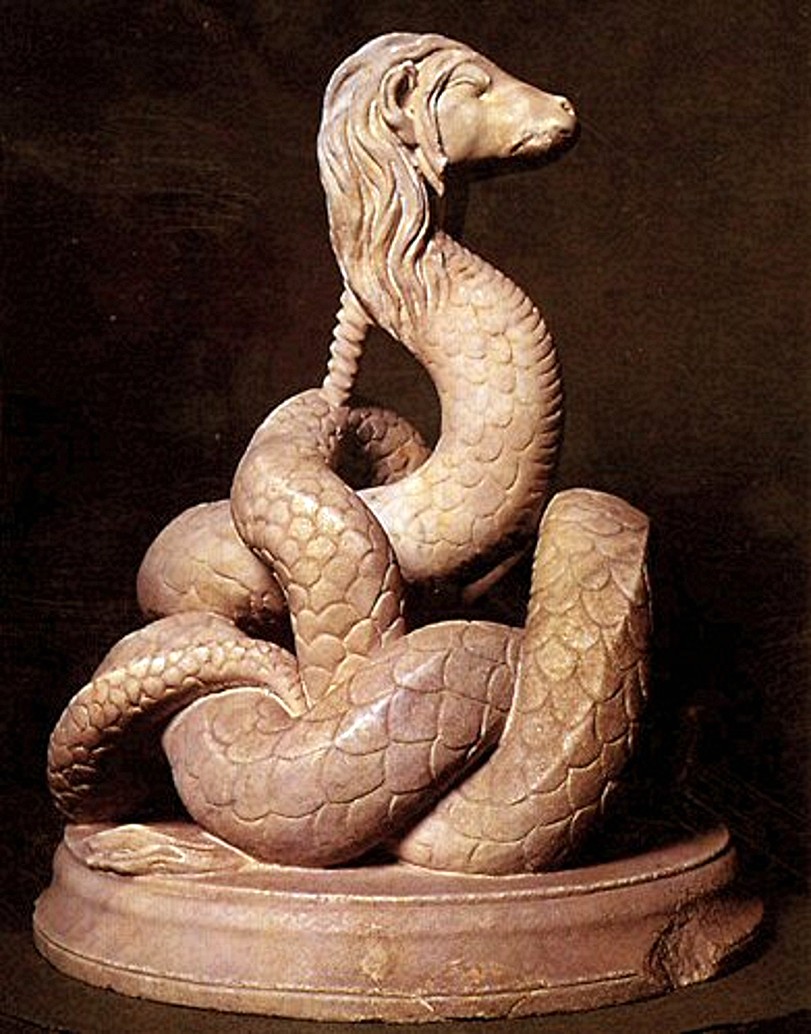

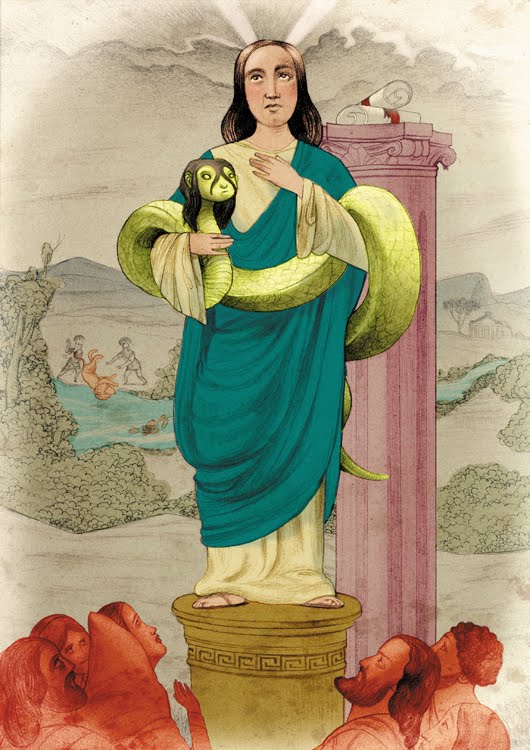

Sometime around 160 AD, Alexander established a snake cult in his home town of Abonoteichus. The sacred snake was worshipped as Glycon, and according to Lucian, it was a hand puppet manipulated by Alexander. Alexander also persuaded the people of Paphlagonians that Glycon was the reincarnation of the god Apollo. Alexander had Glycon prophesying and offering advice on healing. The cult grew enormously popular and attracted many followers from all over the Eastern Mediterranean.

Lucian writes that Glycon would give ‘nocturnal’ oracles and advise, but only to those who paid. One source claimed that the shrine of the snake god provided 80,000 oracles, paid handsomely for each one. Alexander and his circle must have been fabulously rich. Lucian relates that many people asked Glycon questions and often received answers that were nonsensical or irrelevant. Even so, the faithful came in droves.

Many infertile couples would bring gifts to the shrine in the hope that they would become pregnant. Because of the popularity of his cult, Alexander became very influential in Asia Minor, marrying the daughter of the governor.

The Snake God and Roman Emperors

The 160s AD were exceedingly difficult ones for the Roman Empire. It was ravaged by plague and suffered greatly due to wars with German and other tribes. This meant that many people were willing to believe that Glycon channeled the divine. Versified oracles from Glycon were found inscribed on amulets from the 2nd century AD, attesting to the popularity of the cult.

Alexander was personally summoned by Marcus Aurelius in order to provide oracles, and thus went to Rome. The emperor, faced with a major battle with the Germans on the Danuban frontier, asked Glycon how to win. The snake-god (or glove puppet) told Marcus Aurelius that he would win if he sacrificed two lions by drowning them in the Danube. The battle nonetheless was a disaster for the Romans, one of their greatest defeats in the Macromannic War.

However, this does not seem to have ended the influence of the snake-cult in the Roman Empire. Instead, its popularity grew and is credited with the expansion of the town of Abonoteichus, which was renamed Ionapolis.

The End of Alexander of Abonoteichus

The power and respect that Alexander and his cult held in the late 2nd century AD is evidenced by the discovery of coins that depict Glycon.

The cult of Glycon outlived Alexander, and there is evidence that it was still widely practiced in parts of the Aegean a century after his death. Lucian relates that Alexander declared he would live until he was 150, but died about the age of 70 of a terrible disease.

It appears that the glove puppet was abandoned and Glycon was worshipped in an abstract form. There is some evidence that the religion spread to the region around the Danube. There are also indications that Alexander came to be regarded as the son of Asclepius. It is believed the cult of Glycon finally disappeared in the 4th century AD, after the Christianization of the Roman Empire.

Conclusion

Alexander of Abonoteichus was likely a false prophet and a fraud. The cult of Glycon is testament to the search for meaning in a time of crisis. Alexander was able to use a glove puppet to make himself rich and powerful, eventually establishing a religion that lasted centuries.

References:

Lucian (1925). Alexander the False Prophet. Translated by A Harmon.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.