By Edward Whelan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Ovid (43 BC-17/18 AD) is one of the great poets of Rome and indeed of the classical world. He is still studied and read to this day and his works, especially the Metamorphoses has consistently maintained its popularity. While he is remembered as a poet of love and joy, Ovid was, in his real life, an exile who suffered greatly.

Statue (1887) by Ettore Ferrari commemorating Ovid’s exile in Tomis (present-day Constanța, Romania)

The life and career of Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso was born in the provincial town of Sulmo, some 100 miles (140 km) from Rome, into an equestrian family. His father had the means to send Ovid and his brother to Rome to further their education. There, Ovid studied rhetoric but was more interested in verse. Based on his autobiographical poems, he travelled widely in Greece and Italy and later held a number of minor positions in the government. Soon though, he dedicated himself to poetry and rapidly became one of the leading lights of the Roman literary world.

At first, Ovid wrote love poetry but later went on to compose larger workers, such as the Metamorphoses and the Fasti. By 8 AD he was one of the best-known literary figures in Rome and friends of great poets such as Horace. Then, for reasons unknown, he fell out of favor with Augustus and his life became a nightmare.

An illumination of the story of Pyramus and Thisbe from a manuscript of William Caxton’s translation of the Metamorphoses (1480)—the first in the English language

Ovid’s crime

In AD 8, the poet was banished from Rome by the personal orders of Augustus without due process. Ovid was a friend of Augustus’ granddaughter, Julia the Younger, who, along with her husband, were implicated in a plot against the First Emperor. While the exact reasons for Ovid’s exile are not known, it has been speculated that Ovid knew of the conspiracy and did not disclose it. There are others who believe that he helped Julia in her many affairs, which scandalized Roman society and angered the severe Augustus. Some have suggested that the poet, who was something of a Casanova, may have had an affair with the granddaughter of the Emperor.

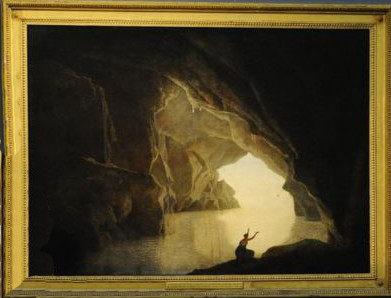

Julia the Younger was imagined in Grotto in the Gulf of Salerno by Joseph Wright of Derby in 1774.

Yet another theory was that Ovid’s poetry, which celebrated love and extra-marital affairs, was contrary to the moral reforms of Augustus. All that Ovid states about his exile was that it was a result of “a verse and a mistake”. The banishment, however, meant that Ovid had to leave his beloved wife and his family.

Exile in Tomis, Black Sea

Ovid was sent to the outer reaches of the Roman Wold. He was ordered to stay in Tomis, which was on the coast of the Black Sea in what is now Romania. It was part of the Kingdom of Thrace, a client state of Rome.

Tomis was mainly inhabited by Thracians who were shepherds, constantly armed to defend themselves and their herds from raiders and wolves. The town was only superficially civilized, and no one spoke Latin. In his poems, he describes the hardships he experienced among the natives and the fears he had; Ovid was constantly at risk from the barbarian tribes who lived in the region.

Over time, however, the affable poet made friends with many of the local tribes’ people, especially the Gaetae, whom he refers to as Scythians. These were nomads and he writes’ about them in some of his most memorable poetry.

‘Ovid among the Scythians’ (1862) by Eugène Delacroix.

Ovid suffered greatly during his exile and he and his wife made many pleas to the Emperor to allow him back to Rome. However, Augustus never relented, and Ovid was never to see his beloved spouse and city again. When Augustus died, the poet and his family had real hopes that the order of banishment would be lifted. Unfortunately the successor of Augustus, Tiberius, was a cruel man; he continued to forbid the poet to return. Eventually, Ovid became somewhat reconciled to his fate, as can be seen in his later poems written at Tomis.

Works in Exile

During his sad and lonely years on the Black Sea Coast, the poet matured as an artist. There, he wrote two great works, the Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto. The themes of these works are his love for Rome and his exile. The Tristia, in particular, contains some of his most powerful poetry. Also during this time, he wrote the Fasti, a series of books on the history of Rome, which may have been written to win the favor of the Emperor. This was left unfinished at his death and was published posthumously. It is believed that several works written by the great poet were lost during his banishment.

Scythians at the Tomb of Ovid, by Johann Heinrich Schönfeld

Ovid’s Death

Ovid died of unknown reasons in Tomis in 17 or 18 AD, far from his family and friends, and was buried in Tomis. His poetry became more popular than ever and was to prove very influential. Interestingly, the order of banishment was only revoked in 2017, by the Roman city council.

Reference

Fairweather, Janet. “Ovid’s autobiographical poem, Tristia 4.10.” The Classical Quarterly 37, no. 1 (1987): 181-196.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.