By Ben Potter

It’s a story with which we are all well-familiar… that of the first emperor of the civilization that shaped the western world, Rome.

Octavian Augustus rose to power following the assassination of Caesar, though only by overcoming the traitor-in-chief Brutus, and his ally Cassius, at the battle of Philippi in 42 BC.

His power was then consolidated following the battle of Actium in 31 BC, at which he defeated “Antony… with him also, a shameful thing, his Egyptian wife” (Cleopatra).

These words of the poet Virgil ring in harmony with so many from the time. This is because it was an era with so many highly gifted poets, ones who were universally full of praise for the leader of the state.

While we refer to the likes of Shakespeare, Marlowe and Webster as ‘Elizabethan’ or ‘Jacobean’, those adjectives merely denote the time periods during which these men of letters were active. The likes of Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Propertius and Tibullus were ‘Augustan’ in mind, body and soul, rather than solely in chronology.

But in a world where the leader is suddenly, brutally and absolutely in command, the question almost inevitably rises: to what extent can we rely on contemporary poets to express their true feelings about Augustus?

Well… the Augustan poets were certainly not backward in coming forward when it came to praising the Emperor.

Reams of paper (well… papyrus) were spent glorifying the new boss. Though ‘glorifying’ is perhaps not a strong enough word; much of the language used by the poets actually attempts to compare the object of their panegyrics to a god:

“Some council of the gods will soon receive you” – Virgil, Georgics.

“Jupiter rules the citadels of heaven and the realms of all the immense three-natured universe ; the earth Augustus governs, each of them Father and Leader” – Ovid, Metamorphoses.

Likewise Horace’s Odes are littered with such allusions and Virgil’s Aeneid is a piece of epic propaganda which attempts to legitimize Augustus’ reign and prove his divinity.

The idea of equating a man to a god is (ironically) a trifle hard to swallow in this day and age. However, this would not have been so at the time under discussion. Leaving aside the fact that Roman society was polytheistic and so the quota of gods could never be fully reached, Augustus was literally a god.

Upon conquering Egypt he became the Pharaoh, no mere leader, intermediary, or ruler by Divine Right, but an actual god.

In addition, Julius Caesar was posthumously deified – Haley’s Comet passing during his funeral games helped grease the wheels of this idea – and so in Rome too, Augustus was, at the very least, the son of a deity.

Divinity was not the only way in which the poets exalted the Emperor; his building works were also praised.

Suetonius famously reports that Augustus boasted he “found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble”.

In Propertius 2.31, the poet makes a reference to one such example, the mighty Temple of Apollo on the Palatine. However, this could also be interpreted as a reference to divinity, as Augustus’ residence adjoined the fantastic structure. What is more, the mention of the temple’s ‘Punic columns’ forces us to think of Augustus’ victory over Cleopatra (and thus Antony).

Indeed, the battle of Actium was another favoured topic the scribblers dwelt on. Epode 9 of Horace deals with the subject at length and states of the leader that “not even Africanus equalled him”. To be considered greater than the scourge of Hannibal was just about the highest praise one Roman could bestow on another.

So Augustus brought peace and prosperity to the Empire, he was literally a god on earth, and he rebuilt a decrepit and decaying Rome. Why then is there any doubt that the poets winged worship was anything other than genuine?

Well, one reason would be the client-patron relationship. The patron in question was, crucially, a close friend of Augustus. He was a man named Maecenas.

He had Virgil, Propertius and Horace all firmly under his patronage and pay. The true parameters of the (traditional and formal) relationship are not known, but it is likely Maecenas would have been able to dictate the topic and tone of much poetical output, if not the actual content.

However, there were a few notes of dissent and, being poets, these came in response to Augustus’ Leges Iulia, his laws championing a lifestyle of monogamy, sobriety and fecundity.

For example, in Propertius 2.7, the poet unequivocally repudiates the Augustan ideal by claiming that he is not going to marry and breed simply to swell the ranks of the dilapidated army: “there will be no soldier from my blood”.

A step further is Ovid’s Art of Love which is basically a handbook on how to seduce women!

How could Ovid get away with something like that in an absolutist regime? Well… he couldn’t. He was exiled from Rome in 8 AD.

Ovid himself described the causes of his exile as “carmen et error” – a poem and a mistake. The poem in question is obviously the Art of Love, but the mistake, intriguingly, remains unknown.

Scholars have enjoyed guessing what it may have been, but most conclude that he witnessed or participated in a sex scandal involving a member of the imperial family. There is, however, no evidence whatsoever to corroborate this.

Even after his exile, Ovid continued to write praiseworthy prosody from his Romanian sanctuary, meaning that, up until the end, Augustus still had every major poet in the empire singing and scribbling his praises.

The simple, but slightly unsatisfactory, reason for this is that the poets wanted to praise the emperor.

The lavish praise they heaped onto Augustus’ shoulders merely reflected his popularity with both the plebeians and aristocracy alike. As a matter of fact, the plaudits from Horace and Virgil began in the 30’s BC, before it was clear Augustus would be the undisputed future of Rome and long before he had absolute power.

This is hardly surprising… Augustus took Rome from being divided, demoralised, socially and religiously depraved, and on the brink of bankruptcy and famine. He transformed it into the commanding power of the ancient world, doubling its territory and winning massive favour with all classes.

True, as absolute ruler he was powerful, untouchable and often ruthless. Thus, the Augustan poets knew on which side their bread was buttered – but fortunately for all concerned, it was the side, given the choice, they probably would have spread it on anyway.

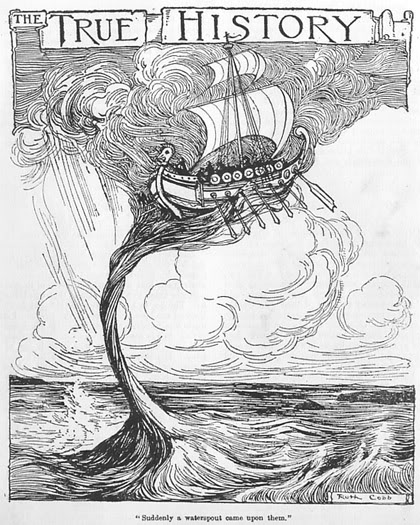

Before long, the explorers are discovered by soldiers riding on the backs of giant vultures. The men are detained and brought to the court of the king of the moon.

Before long, the explorers are discovered by soldiers riding on the backs of giant vultures. The men are detained and brought to the court of the king of the moon.

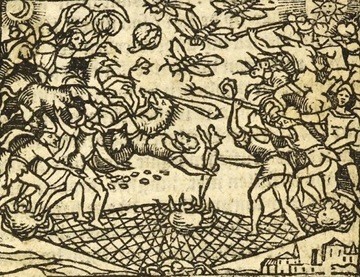

Cloud-centaurs, flying horse/human hybrids from the milky way, arrive from nowhere and attack the disarrayed moon forces. The army or Endymion is defeated and the human explorers are taken as hostages.

Cloud-centaurs, flying horse/human hybrids from the milky way, arrive from nowhere and attack the disarrayed moon forces. The army or Endymion is defeated and the human explorers are taken as hostages.