Written by Cynthia C. Polsley, Ph.D., Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

And I said to him: ‘Who are those two poor sinners

who give off smoke like wet hands in the winter

and lie so close to you upon the right?’

‘I found them here,’ he answered, ‘when I rained

down to this rocky slope; they’ve not stirred since

and will not move, I think, eternally.

One is the lying woman who blamed Joseph;

the other, lying Sinon, Greek from Troy . . .’

Dante’s Inferno, Canto XXX. 91-98

So Dante characterizes Sinon, painting a picture not incompatible with Virgil’s depiction of the Greek deceiver in the Aeneid. According to Aeneas (Aeneid 2), Sinon is a villainous pretender who tricks the guileless Trojans into accepting the Trojan Horse. Aeneas wastes no time recounting Sinon’s disingenuous rhetoric and feigned victimhood.

Yet, Virgil’s Sinon hints at complexity to the character. In a host of voices telling his story, Sinon is more than a simple deceiver. What is he, really? Who is relaying his words, and what does each speaker believe of him? These questions are not just important to Sinon’s legacy but help to define his identity at any given moment.

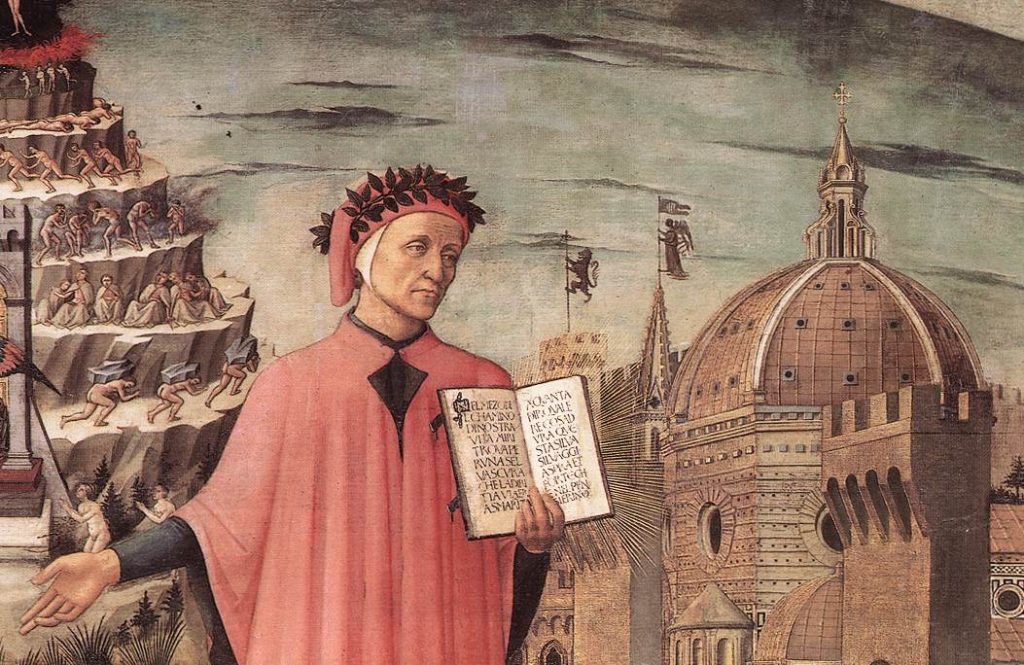

Dante, poised between the mountain of purgatory and the city of Florence, displays the incipit Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita (“Midway upon the journey of our life”) in a detail of Domenico di Michelino’s painting, Florence, 1465.

Virgil’s account suggests such intricacy. Aeneas’s hindsight inevitably affects his representation of Sinon. In 142 lines (Aen. 2. 57-198), mostly Sinon’s own words, Aeneas remembers the Greek man’s duplicity. The details of his recollection are influenced by later knowledge, including a fuller recognition of the Trojans’ credulity.

We simultaneously receive multiple, conflicting claims and viewpoints, including those of 1) the scheming Sinon, a “desperate captive;” 2) the true Sinon, with motivations clarified by Aeneas; 3) Priam and the Trojans, merciful and innocent; and 4) Aeneas himself, agonizingly reflecting on the past. Although it is difficult to untangle truths from embellishments, Sinon’s ethics and methods are undebatable. As far as Aeneas is concerned, the Greeks took Troy by subterfuge.

Before Virgil, There Was . . .

Seeing through Trojan eyes, Aeneas offers an account of Sinon that is no more flattering than Dante’s. But what of the Greeks’ view? Surely their portrait of the man would have been more positive, especially in light of surviving literature. After all, Sinon was an important player in Troy’s defeat.

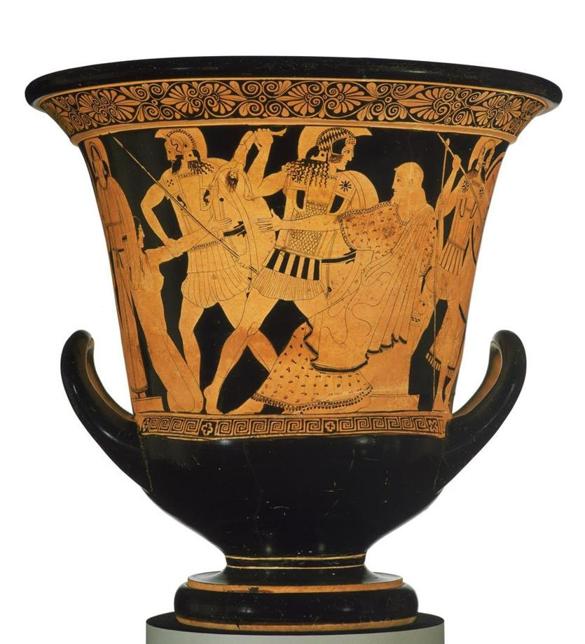

Sinon as a captive in front of the walls of Troy, in the Vergilius Romanus, 5th century AD

Or was he? Sources differ. In Book 4 of Homer’s Odyssey, Menelaus omits Sinon altogether from the Trojan Horse story (Od. 4. 271-274). The Little Iliad, summarized by the obscure author Proclus, similarly neglects Sinon’s role in convincing the Trojans to accept the Horse. While his specific agency is ambiguous, Sinon acts as a spy from within Troy and secretly signals the Greeks (Little Iliad 11).

The Sack of Ilium is likewise short on detail, albeit evincing the bare outline of Virgilian mythology. The Trojans decided to dedicate the Horse to Athena and to feast in celebration. However, after two serpents appear as an ill omen and kill the priest Laocoön and one of his sons, Aeneas and his people anxiously withdraw to Ida. Sinon, who earlier entered the city “by pretense” (προσποιητός, Sack of Ilium 1), lights his beacons to begin the Greek invasion.

Beyond Epic Cycle summaries and fragments, Greek tragedy puts Sinon front and center. Sophocles made Sinon the main character of an entire play called Sinon. Unfortunately, only four disjointed words survive. Since virtually nothing of the play is extant, the Sophoclean Sinon remains mysterious.

Still, certain readers have detected something of the stage in the Virgilian Sinon and his speech — not only in its style, but also its contents, such as the mention of Sinon’s supposed relative Palamedes, treacherously slain by Odysseus, or the sacrifice of Agamemnon’s daughter Iphigenia.

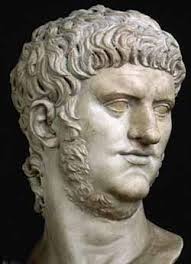

Depiction of Virgil

Fast Forward from Virgil

Long after Virgil, another Greek retelling imagines Sinon as a resolute hero. Quintus of Smyrna, writing his Fall of Troy in the third or fourth century A.D., interprets Sinon as a respectable figure. When Odysseus calls for a brave man to fool the Trojans, Sinon is the only Greek willing to undertake the mission. He proclaims that he will either succeed or die trying (12.250-251).

Praising his newfound courage, the overjoyed Greeks deem him divinely appointed to end the war (12.253-258). Whereas the Aeneid focuses on his shrewd rhetoric, Sinon here is a valiant volunteer, identified by the narrator as the man fated to accomplish the “great deed” (12.244).

Not that words are absent from Quintus’s Sinon. In fact, his speech’s content is not dissimilar from that of the Aeneid. Yet he speaks more briefly, and to listeners who cruelly threaten, mutilate, and beat him. As in the Aeneid, Sinon declares that he has barely eluded Odysseus’s deadly designs — not by physical escape, as in Aeneid 2.132-144, but by clinging to the sacred Horse for safety (12.379-386).

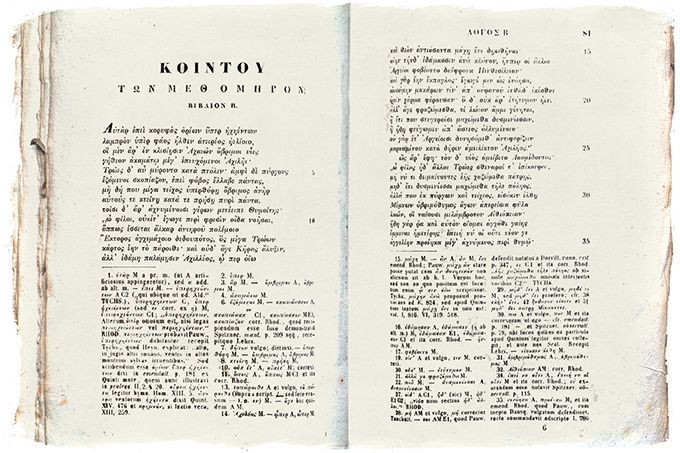

Quintus Smyrnaeus (Kointou Kalabrou paraleipomenōn Omērou) from 1505, printed by Aldus Manutius in Venice with handwritten notes by Conrad Gesner. Source: Luwian Studies.

Hadjittofi remarks that this Sinon’s “fundamental strength is endurance,” and that “the virtue by which Sinon wins the war for the Greeks is essentially, and ironically, Roman (firmitas, or constantia).” Remarkably, “Sinon of the Aeneid becomes here a real hero since he is willing to risk life and limb in the hands of the barbaric Trojans for the glory of Greece. . . . The slander against Greeks, that they are typically deceitful and manipulative, is erased . . . , and the ancestors of the Romans are, instead, depicted as brutal and uncivilized.”

The different treatments by Virgil and Quintus are instructive. Aeneas paints a picture of the Trojans as pious and genteel, suitable Roman ancestors. This image is in opposition to the presentation of the Trojans by Quintus, who is less concerned with honoring Roman heritage.

Sinon’s forceful rhetoric in the Aeneid allows Virgil to demonstrate oratorical prowess and to accentuate Trojan kindness. Conversely, handling the Sinon episode from a more Greek view, Quintus’s shows how heroic Sinon can appear when an author rejects Trojan/Roman interpretation.

Virgil Reading the Aeneid to Augustus, Octavia, and Livia by Jean-Baptiste Wicar, Art Institute of Chicago

A milder, comparatively middle-ground account is found in the Fall of Troy by the native Egyptian Tryphiodorus, Quintus’s contemporary. Also writing in Greek, Tryphiodorus seems to rely more heavily on the Aeneid’s tale. On the one hand, unlike Virgil’s, his Sinon is heroic and brave. Sinon readily undergoes physical beating by the Greeks so that he may appear more credible. When the time comes, the “wily hero” (ἀπατήλιος ἥρως, 220) staggers into view, bloodied and beaten, and kneels before Priam to deliver a stirring supplication (258-282).

On the other hand, like those of Virgil, Tryphiodorus’s Trojans are generous and caring. Priam treats Sinon gently and clothes him (283, 304-305). Overall, this version and its characters exhibit the Aeneid‘s enduring influence. At the same time, they display a blended opinion of Sinon’s behavior and ethics. The Trojan perspective of Sinon is not always as primary as in the Aeneid. And even there, once upon a time, the Trojans viewed Sinon differently than Aeneas does later.

A Slippery Character

What do we make of Sinon, then? Wheedler, warrior; cajoling, courageous? Ultimately, it depends on who is doing the talking — not Sinon himself, speaking without another interpreter, but Sinon as a speaker presented by others, interpreted by those who suffered or succeeded due to his words and actions.

The Fall of Troy, by Johann Georg Trautmann (1713–1769). From the collections of the Grand Dukes of Baden, Karlsruhe.

Furthermore, the perceived distance from Sinon as a historical figure or a story character affects a narrator’s portrayal. For the most part, Virgil’s Sinon leaves the greatest impression on the mythological tradition: for Aeneas, Sinon’s legacy is a significant reminder of how easily reality can be distorted. Throughout the Aeneid, always haunted by dark memories of events at Troy, Aeneas lives under the shadow of Sinon’s treachery.

But Sinon is not always a grim embodiment of past defeat. To some, he is a powerful orator to be admired; to others, a heroic martyr, ready to sacrifice everything for a common cause. The subtle multiplicity of perspectives captured in the Aeneid 2 episode turns out to be a testament to Sinon’s complexity. Whatever the case, it seems that Dante’s “lying Sinon, Greek from Troy,” “not stirred since” discovery and who, it is thought, “will not move . . . eternally,” may not have been so eternally unmoved after all.

References

- Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri: The Inferno. Trans. Allen Mandelbaum. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

- Balsdon, J. P. V. D. Romans and Aliens. London: Duckworth, 1979.

- Campbell, Celia. “Sinon and the Hatred of Odysseus. Vergilius, Vol. 63 (2017): 3-20.

- Hadjittofi, Fotini. “Res Romanae: Cultural Politics in Quintus and Nonnus.” In Quintus Smyrnaeus: Transforming Homer in Second Sophistic epic. Baumbach, Manuel, Silvio Bär, and Nicola Dümmler, eds. New York: Walter De Gruyter, 2007.

- Hardie, Philip R. The Epic Successors of Virgil: A Study in the Dynamics of a Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Horsfall, Nicholas. Virgil, Aeneid 2: A Commentary. Mnemosyne, Supp. 299. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

- Keith, Arthur L. “The Sinon Episode in Vergil.” The Classical Weekly, Vol. 15, No. 18 (Mar. 1922): 140-42.

- Lloyd-Jones, Hugh. Sophocles. Fragments. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996.

- Lynch, John P. “Laocoön and Sinon: Virgil, ‘Aeneid’ 2.40-198.” Greece & Rome, Second Series, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Oct. 1980): 170-79.

- Sutton, Dana F. The Lost Sophocles. Lanham: University Press of America, 1984.

- ter Vrugt-Lentz, J. “Sinon und Zopyros.” Mnemosyne, Fourth Series, Vol. 20, Fasc. 2 (1967): 168-71.

- [viii] Hadjittofi 2007: 368. For an idea of Roman consideration of the Greeks, compare Balsdon 1979: “With the Greeks the Romans had a love-hate relationship. For the broad mass of contemporary Greeks, the majority of Romans at all times in their history felt unbridled contempt. . . Greeks were (crooks and) sycophants who could never be trusted on oath to tell the truth, for they regarded the giving of evidence on oath as ‘a great game'” (ibid.: 30, 31-32).