By Ben Potter and Van Bryan

“Money…there’s nothing in the world so demoralizing as money.”

So says the 5th-century Greek playwright, Sophocles.

Now, dear reader, we’re a student of the classics. We believe that an understanding and appreciation for the literature and history of antiquity can lend us perspective. The classics teach us to think critically, ponder more thoughtfully the questions of our humanity.

That being said, we always wished that the ancient Athenian had elaborated on his claim of monetary demoralization.

What about money is demoralizing?

Is it a deficiency of money that demoralizes man?

Or perhaps an excess? Is money the root of all evil? Or is evil the root of all money?

We don’t know. We’re being Socratic and merely asking questions. We’ve only ever claimed to know nothing, and not once have we failed to live up to that standard.

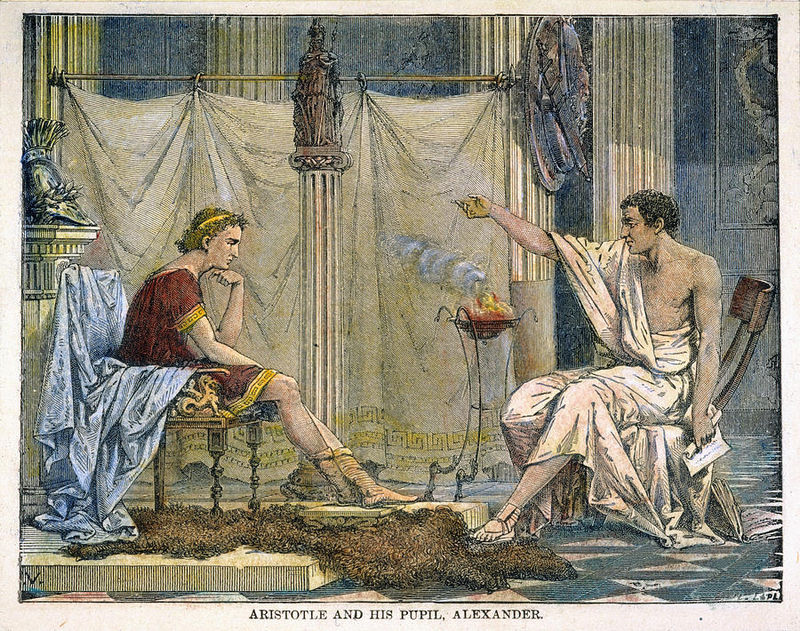

Lucky for us, greater minds than ours have pondered questions of coinage. The ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle, of the 4th century BC, had one such mind.

Perhaps our ancient forefather can lend perspective on this subject, and answer for us an age-old question: what exactly is money?

What is money?

Ancient Greece was a time of firsts for the Western World.

First democratic government? Yep.

First masterpieces in literature? Check.

First academic university? Double check. Plato AND Aristotle founded schools in the classical age.

It’s unsurprising then that the ancient Greeks were also responsible for minting some of the first coins in the Western world.

Perhaps even more unsurprising is that this was almost immediately followed by the first embezzlement scandal and an ancient version of the military-industrial complex.

See…we really are influenced by the Greeks.

Ancient Greek Tetradrachm

Note: New subscribers to our monthly subscription can recieve their own classical gold tetradrachm for free.

Learn more here.

The ancient Greek drachma enjoyed popular usage starting in the Archaic Age of Greece (around 600 BC) right up until the Roman Empire. Ancient coins were originally minted from electrum, a naturally occurring alloy, but over time gold and silver became the preferred metals.

The rising economic influence of the Greeks during the 5th century meant that the ancient drachma was widely accepted across the known world. Ancient coins have been found in Egypt, Rome, and Syria. They even reached as far as the western dwelling Celts.

But all of this so far is just nickel and dime stuff. Practice your best chin stroking, now we get philosophical.

Aristotle, a man who is often regarded as one of the most prolific and influential philosophers of the Western world, had a few ideas on money.

Unlike his predecessor and teacher, Plato, Aristotle felt no need to justify the existence of money. Being the practical guy that he was, Aristotle considered the necessity of money to be self-evident.

|

When the inhabitants of one country became more dependent on those of another, and they imported what they needed, and exported what they had too much of, money necessarily came into use. |

|

|

And not to mention, Aristotle says somewhat patronizingly, …

|

The various necessaries of life are not easily carried about! |

|

|

Importantly, Aristotle did not claim that money was wealth. Rather, money represented wealth.

|

How can that be wealth of which a man may have a great abundance and yet perish with hunger, like Midas in the fable, whose insatiable prayer turned everything that was set before him into gold? |

|

|

Money, to Aristotle, represents olives in the orchard, vases from the potter, wine from the vineyard. Money wasn’t wealth, but it could measure wealth.

Fair enough, we’ve talked about what money is not. What, then, is money?

Well, Aristotle says that money should ideally be five things…

-

- Durable – it must survive the trials and tribulations of daily life, i.e. of being carried around in people’s pockets, purses, or even in the mouths of the newly deceased.

-

- Portable – a small item should be of a high value.

-

- Divisible – breaking a coin, either figuratively or literally, should not affect its relative value.

-

- Fungible – mutually exchangeable i.e. it doesn’t matter which particular coin you have as long as you have one.

- Intrinsically valuable – the coin’s material should be a worthwhile commodity (mint coins from gold not concrete).

Ignoring this 5th principle, history tells us, is what can be particularly disastrous.

The Crisis of the 3rd Century

At the outset of the Roman Empire, starting in 27 BC, the preferred Roman currency was the silver denarius. Rome’s first Emperor, Augustus, minted coins that were 95% silver.

Ah, but what good idea couldn’t be improved with a little monetary manipulation?

Ancient Roman Denarius depicting Titus

The coinage was debased over the centuries; so much so that by 268 AD, there was just under .5% silver in the denarius.When questioned about the devaluation of the currency, Emperor Caracalla (who ruled from 198 to 217 AD) held up his sword and declared…

|

Not to worry. So long as we have these (gesturing to the sword), we shall not run short of money. |

|

|

How do you like that for a monetary policy?!

Even non-economists can probably guess what happened next. Hyperinflation ran rampant in the Empire. Prices during this period rose as much as 1000%. This is often referred to as “the crisis of the 3rd century”.

Over the next fifty years, 26 different men would claim the seat of power, often through military force. As for Emperor Carcalla-in 217 AD his own soldiers stabbed him to death when the Emperor stopped to take a leak.

History really is fascinating…

Perhaps the madness is best summed up by the 18th century historian Edward Gibbon, when he commented that the great wonder of the Roman Empire was not that it fell, but rather that it lasted as long as it did!

Nothing More Demoralizing?

Aristotle’s ideas have been used throughout the ages in order to justify or denigrate various economic policies and innovations; from fiat printing to the most recent phenomenon of crypto-currencies.

By now we’re feeling Socratic again. Are Aristotle’s ideas on money outdated or, perhaps worse, standing in the way of progress? Or are we, like the Romans, teeing off for our own crisis of the third century?

Over the centuries the great teacher has been proven wrong (he contended that flies had four legs and that women had fewer teeth than men). So, at times, society was only able to progress once it had rejected Aristotle’s assertions. Do his ideas on sound money fall into this category of outdated philosophical fodder?

Again, we have no answers… Perhaps that’s the most demoralizing thought of all.