The AK-47 of the Ancient Near East

By Cam Rea

The Scythian bow was the AK-47 of the Ancient Near East and the weapon of choice to dominate the battlefield. Even though the bow was uniquely designed to deliver the utmost damage, the arrow itself was even nastier! Scythians created their arrowheads for maximum penetration of the opponent’s armor. Beyond that, Scythian arrowheads were extremely poisonous.

But before we pick our poison, we must pick our point.

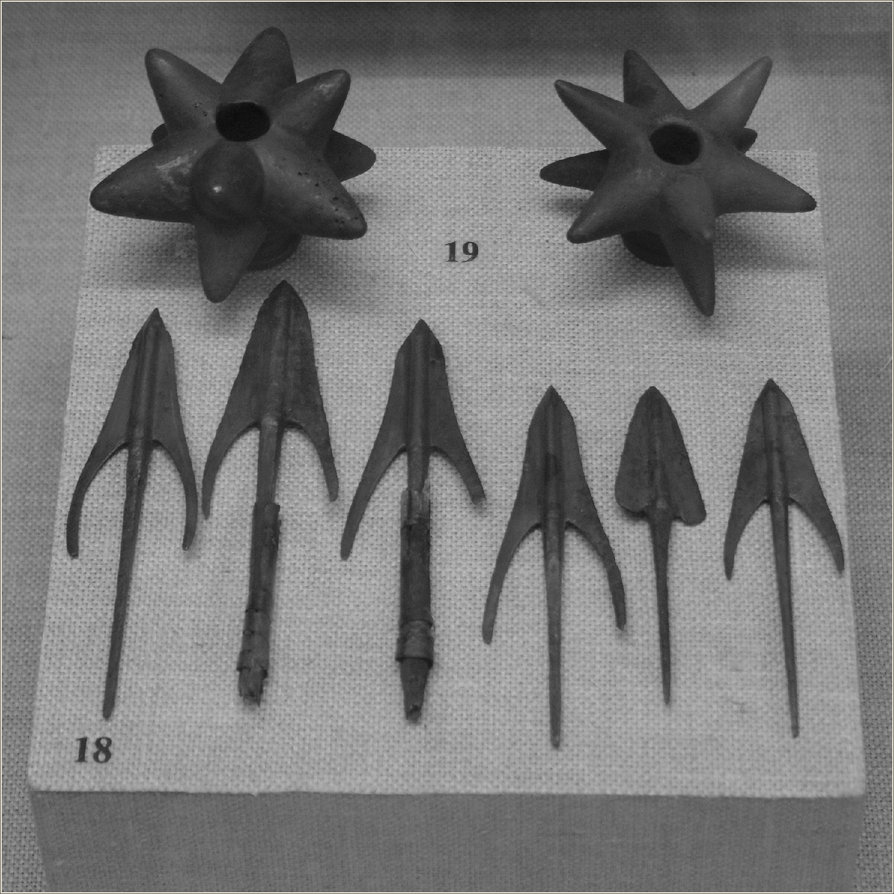

The Scythian arrowhead

The Scythian arrowhead, also known as a “Scythian point,” was a trilobate shape, designed like a rocket or bullet with three blades extending from the body. Some of the arrowheads had protruding barbs, while others lacked this painful extra. The trilobate was usually made of bronze, while the shaft used to deliver the arrowhead was made of reed or wood and was roughly 30 inches long. The design and craftsmanship employed was brilliant, for its aerodynamic body made it extremely practical to use against the finest and toughest of armor.

The Scythian point originated around the 7th century BCE, suggesting that Scythians developed the weapon in order to pierce Assyrian armor, as Scythians and Cimmerians were indeed at war with Assyria on and off during that time period. Now, this was not the only arrowhead style or material used by the Scythians, for some arrowheads were made of bone, stone, iron, or bronze. As for shape, some looked like small spearheads, while others were leaf-shaped, which may have been used for hunting. The discussed trilobite shape, however, was most likely used for combat purposes.

Besides the lethal design of the Scythian trilobite point, another nasty feature was the poison. Not only were these ancient fighters experts at archery, but also in biological warfare. Fortunately, or unfortunately depending on how you see it, the Scythians had a wide variety of deadly poisons to choose from. The not so friendly reptiles inhabiting the area included the steppe viper, Caucasus viper, European adder, and the long-nose/sand viper.

Map of Scythia and the Persian Empire

Truly, the Scythians had a vast arsenal of snake venoms of all degrees at their disposal. The book titled, “On Marvelous Things Heard,” by Pseudo-Aristotle, which was a work written by his followers, if not written in part by Aristotle himself, mentions the Scythian handling of snakes and how to extract their poison:

“They say that the Scythian poison, in which that people dips its arrows, is procured from the viper. The Scythians, it would appear, watch those that are just bringing forth young, and take them, and allow them to putrefy for some days.”

After several days passed, the Scythian shaman would then take the venom and mix it with other ingredients. One of these concoctions required human blood:

“But when the whole mass appears to them to have become sufficiently rotten, they pour human blood into a little pot, and, after covering it with a lid, bury it in a dung-hill. And when this likewise has putrefied, they mix that which settles on the top, which is of a watery nature, with the corrupted blood of the viper, and thus make it a deadly poison.”

The Roman author Aelian also mentions this process, saying, “The Scythians are even said to mix serum from the human body with the poison that they smear upon their arrows.” Both accounts show that the Scythians were able to excite the blood in order to separate it from the yellow watery plasma. Once the mixture of blood and dung had putrefied, the shaman would take the serum and excrement and mix it in with the next ingredient, venom, along with the decomposed viper. Once the process was complete, the Scythians would place their arrowheads into this deadly mixture ready for use.

The historian Strabo mentions a second use of this deadly poison:

“The Soanes use poison of an extraordinary kind for the points of their weapons; even the odour of this poison is a cause of suffering to those who are wounded by arrows thus prepared.”

So the arrowhead was poisonous, but why stop there? Sometimes they ensured that the barbs on the arrowhead were also coated with the deadly concoction. The Roman poet Ovid, who was exiled to the Black Sea, got a good look at these poisonous plus arrows and reported them as “native arrow-points have their steel barbs smeared with poison, carry a double hazard of death.” He also described the poisonous ingredient as “yellow with vipers gall.”

To get a better understanding of this “double death,” Renate Rolle elaborates further on the barbed arrowheads: “These arrowheads, fitted with hooks and soaked in poison, were particularly feared, since they were very difficult to remove from the wound and caused the victim great pain during the process.” A very grim picture, without question. To be struck by an arrowhead with barbs or hooks, poisoned with putrefied remains, would indeed be horrific.

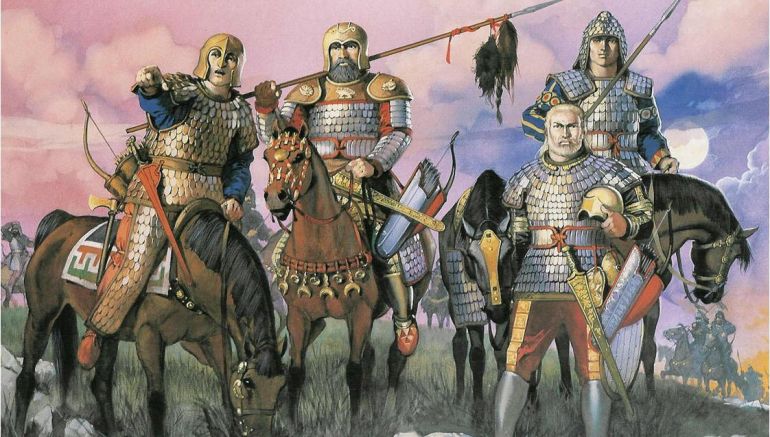

Scythian–ancient nomadic Iranian–warriors on the steppe

With all these different poisons used by the Scythians, they had to know how to tell what was what in their gorytus, or case for holding the bow and quiver of arrows. The length of the gorytas was relatively shorter than the bow itself, leaving the weapon partially exposed. It also had a metal covering for the arrows, most likely to protect the archer from scraping his skin across the poisonous arrowheads.

The Scythians would paint their arrow shafts in the color of red or black, while others had zigzag and diamond patterns decorating them. Not so coincidentally, these various patterns painted upon the arrow shafts were the same patterns found upon the various vipers used by the Scythians as their agents of death. Vipers with a zigzag or diamond pattern upon their backs were the most poisonous of all.

Clearly, the painted design was a way for the archer to tell which poison he was using. Additionally, the decorated arrow shafts, when fired at the enemy, likely had a psychological effect, for they must have looked like snakes flying through the air, while the barbs protruding from the point appeared like fangs to the enemy.

So now that the Scythians had their gorytus, stacked with a fierce weapon and deadly arrows, it was just a matter of choosing which chemical killer to use on the enemy.