Written by Katherine Smyth, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

If there is one literary work that has inspired a legacy of artists, poets, and creators, it’s Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Comprising 250 myths and over nearly 1200 lines of poetry, it makes up an impressive 15 books of life-defining narration.

Ovid’s work doesn’t just offer a creation myth, it defines an entire belief system, and although his popularity has faded since the Renaissance, there is still much we can learn from and admire about his literary creation. But, how did Ovid produce this famous work, and what influenced him?

Ancient Beginnings

You might be surprised to know that Ovid’s defining work was actually influenced by Alexandrian poetry, which was written in Ancient Greek with the earliest texts dating to the Archaic period. The most notable contributions to Alexandrian poetry were, of course, the two epic poems, The Iliad and The Odyssey.

Yet, where that tradition focused on myths as a means for moral reflection and insight, Ovid chose a more playful adaption to these tales. This style of the collection, or metamorphosis poetry, can be found in the Hellenistic tradition, with Boios’ Ornithogonia portraying the metamorphosis of birdlife stemming from human origins.

Statue (1887) by Ettore Ferrari commemorating Ovid’s exile in Tomis (present-day Constanța, Romania).

Ovid’s Metamorphoses has been considered an epic, as it is of a significant length, is told in dactylic hexameter, and has over 250 narratives chronicled across 15 books. Whilst the text is unbroken in its chronology, Brooks Otis identified four naturally occurring divisions and stories within the publication, which he refers to as:

- Book I–Book II (end, line 875): The Divine Comedy

- Book III–Book VI, 400: The Avenging Gods

- Book VI, 401–Book XI (end, line 795): The Pathos of Love

- Book XII–Book XV (end, line 879): Rome and the Deified Ruler

However, where epics or epic-like offshoots focus on restraining themselves to one style or genre, Metamorphoses breaks with this tradition by utilizing the themes and tones of many literary styles. These range from the obvious epic to tragedy, and from elegy to pastoral; as such it has defied categorization into any one genre.

So, what did Ovid write about, and what can we learn from its human and immortal metamorphosis?

Metamorphoses is considered to be a comprehensive chronology that recounts the world’s creation through to the death of Julius Caesar – a pivotal event which occurred

only 1 year before Ovid’s birth in 43 BC. As such,

Metamorphoses is also thought to be an example of universal history, as this fulfilled a societal need from the 1st century BC.

Portrait of Ovid, bust in profile to the right, wearing laurel crown; in medallion; illustration to Jephson’s ‘Roman Portraits’. 1794. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Ovid begins his work with the ritual of invoking the Muse, where he makes use of epithetical and circumlocutory traditions. However, it deviates here from the expected extolment of a mortal hero, and instead leaps from story to story with no apparent connection or reason. Ovid’s narration style has been considered arbitrary, and these tales sometimes overlap in their content, when they relate to events that were considered to be central to the world of Greek mythology.

One recurring theme of Metamorphoses is that of Love. That includes personal love or as the personified deity, Amor/Cupid. In Ovid’s work, the gods were continually humiliated and confused by Love, who was usually considered to be a relatively insignificant minor god.

“Thus she disclos’d the woman’s secret heart,

Young, innocent, and new to Cupid’s dart.

Her thoughts, her words, her actions wildly rove,

With love she burns, yet knows not that ’tis love.”

~ Book X

One example is a tale of Apollo, who was so confounded by love that he was unable to think rationally or to even use reason. This portrayal of all-powerful gods made them much more relatable with human passions and experiences and elevated humans to being almost god-like as they battled for superior intelligence and control.

“But the lewd monarch [Phoebus/Apollo], tho’ withdrawn apart,

Still feels love’s poison rankling in his heart:

Her face divine is stamp’d within his breast,

Fancy imagines, and improves the rest:

And thus, kept waking by intense desire,

He nourishes his own prevailing fire.”

~ Book VI

Apollo Pursuing Daphne, by Francesco Albani

However, throughout the narrative, the most apparent and unifying theme is (perhaps not unsurprisingly, based on the title!) metamorphosis or transformation. This significance is announced at the very beginning with the opening line “In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas /corpora” or “I intend to speak of forms changed into new entities”.

Often accompanying this transformation is the theme of violence, usually performed upon a victim whose tale becomes embedded into the natural landscape. This literary theme is the amalgamation of a pursuer seeking their reward, and the thematic tension portrayed between nature and art.

Some of the transformations described include those of humans becoming constellations, animals or fungus. Other transformations are of gender or appearance, yet the metamorphoses are usually hidden within the metatextual poem through the language used to deceive the reader, causing them to question their thoughts or beliefs.

The Influence of the Metamorphoses

When we think about Ovid’s work, it’s easy to relegate it to before the first millennia, that its tongue-in-cheek humor is no longer appreciated or has any influence. But, is that really the case? Not really, as it was only a few hundred years ago we can see Metamorphoses having a huge influence on what we now consider to be classic literature, and as providing significant contributions to historic and cultural identity.

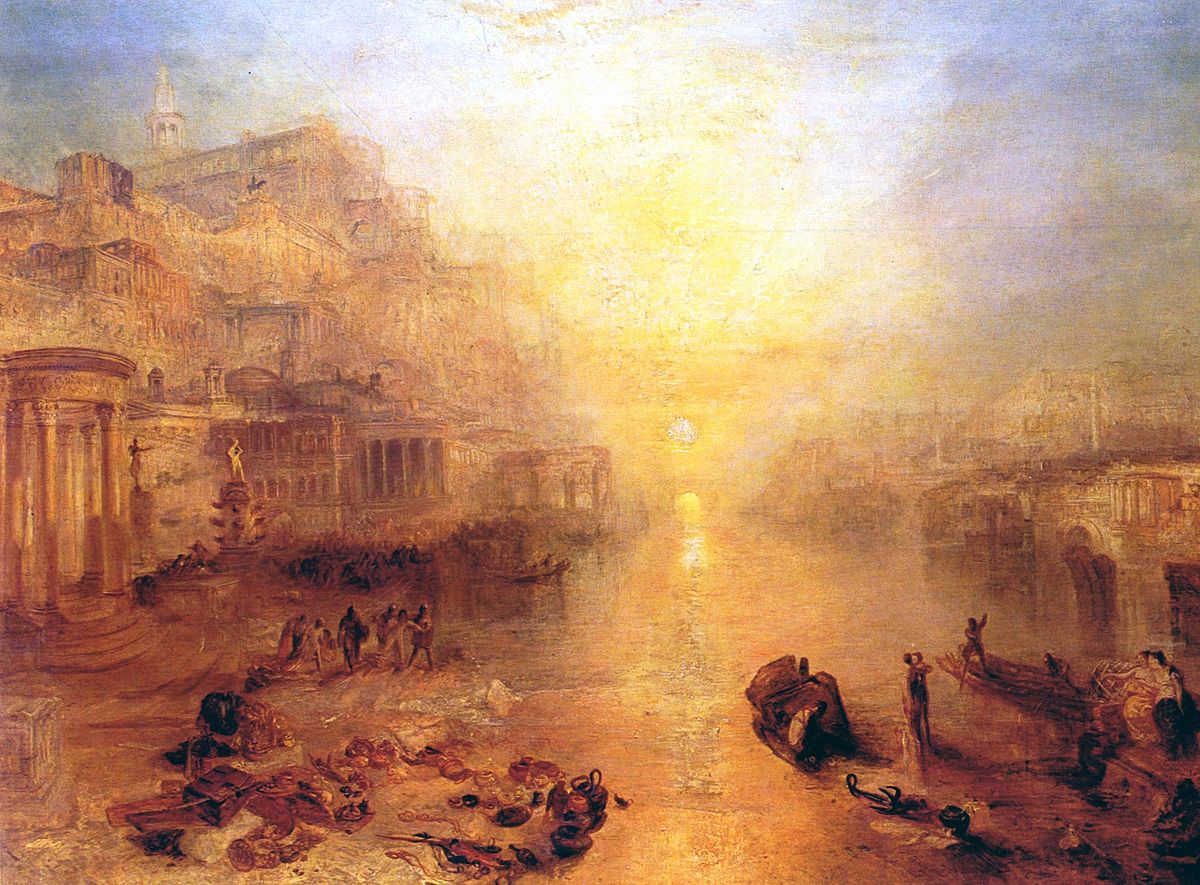

Ovid Banished from Rome (1838) by J.M.W. Turner.

In Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, we have several adaptations that can be identified with a Metamorphoses-base: The Wife of Bath is based on Midas’ story, as is The Book of the Duchess, which is based on Ceyx and Alcyone. We can also see Ovid’s influence in several of Shakespeare’s works, including Romeo and Juliet which is influenced by Pyramus and Thisbe, and even Prospero’s speech in The Tempest, which is almost taken word-for-word from Medea’s speech in Metamorphoses.

Other writers who’ve benefited from Ovid’s influence include John Milton in Paradise Lost, and works by Giovanni Boccaccio, and Dante. During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, both artists and writers benefitted hugely from the renewed interest in Ovid’s work, so much so that it spawned the term “Ovidian”. Although this trend did peter out over the 18th century, towards the 20th century there was another resurgence and appreciation of his work.

Although the first publication of Metamorphoses was available from 8 AD, around Ovid’s exile, no original manuscript survives from the period. There are, however, examples from the 9th and 10th centuries in fragmented form, as well as some complete manuscripts from the 11th century. Fortunately, there are also translations of these manuscripts, with the earliest English version being produced by William Caxton in 1480.

Other English translations date from 1567, by Arthur Golding, and George Sandys in 1621-26. Then in 1717, Samuel Garth produced a translation that was heralded as being produced “by the most eminent hands”, which included contributions from John Dryden, Joseph Addison, Alexander Pope, Tate Gay, William Congreve, and Nicholas Rowe. This translation was printed for many years, well into the 1800s, and was considered to be without any real rival until the 20th century when new translations began to appear, and this trend has continued into the 21st century and the digital age.

Portrait of Ovid by James Godby, after Giovanni Battista Cipriani, 1815. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Transformational Lessons

If we are to learn anything from Ovid’s work, it’s probably these fundamental points: with its power to confuse and overwhelm, Love will humanize even the most god-like beings, and that everything and everyone, even the gods, are subject to the transformative powers of love.

So, don’t try and run from love. If the gods can’t escape it, neither can you!

“The fire of love the more it is supprest,

The more it glows, and rages in the breast.”

~ Book IV

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.