By Eldar Balta, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Xenophon’s Early life

Not much is known of Xenophon from his early years, except that he was son of Gryllus, a wealthy citizen of Erchia, a suburb of Athens. He was born circa 430 BC, and not much is known of his life up to 401 BC. This is when he was, according to his work Anabasis, invited by his friend Proxenus to join the military expedition…one that marked his life and lifetime work. He became a mercenary for Cyrus the Younger against his elder brother, King Artaxerxes II of Persia.

There was, however, one small problem. He was not aware of that fact.

Xenophon in front of the Austrian Parliament Building in Vienna

Xenophon and his Ten Thousand men

This endeavor was hugely influential for both Xenophon, as well as military leaders throughout history. In the end, it provided important lessons on military logistical operations, flanking maneuvers, feints, attacks in specifics and retreat, in general.

Why retreat, you ask? Well, mostly because that’s exactly what the Greeks did. They were expecting a much easier obstacle, a Persian satrap named Tissaphernes (do not forget this name, we will come back to him later). Instead, they faced a great Persian army. Moreover, soon into the expedition the main financial and logistical provider, Cyrus, was killed in the middle of a battle. The chain of events got even worse when shortly thereafter, Greek leaders, generals, and captains were invited to a peace conference… where they were betrayed and executed.

So, the Greek army was left with a simple plan. One, retreat. Two, have Xenophon lead the way back home.

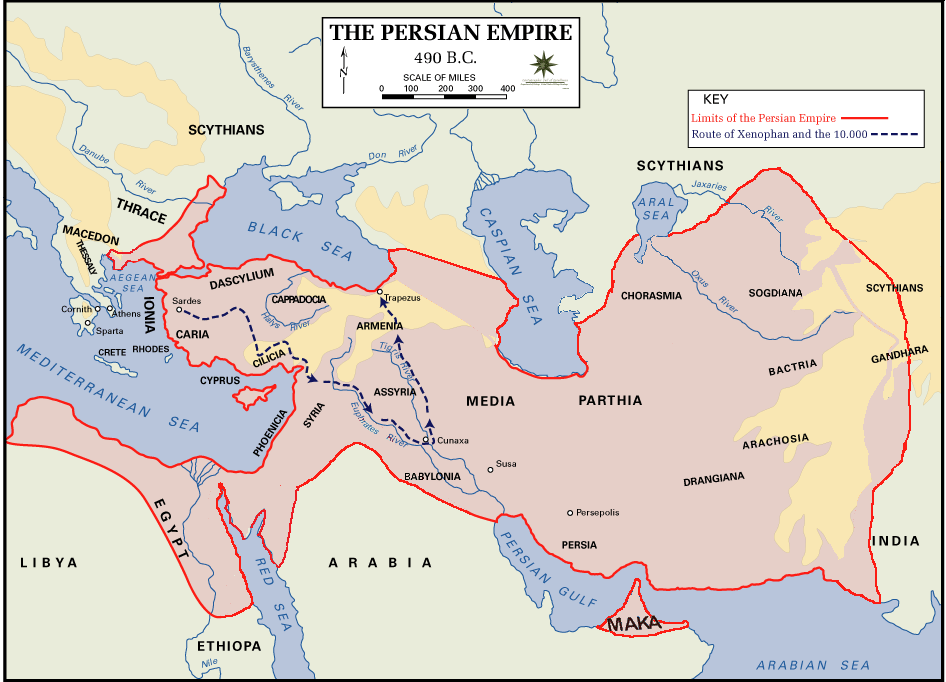

The Route of Xenophon’s Ten Thousand Men

Anabasis, one of Xenophon’s greatest works, is where you can read in detail his struggles and strategies. This epic adventure is the reason why “the centuries since have devised nothing to surpass the genius of this warrior”, as quotes military historian Theodore Ayrault Dodge. We, however, will cut the story short here and say that he got his men safely back home.

Tissaphernes – a name we told you not to forget

Tissaphernes was a Persian satrap and a historical knot that entangles many individual destinies as well as the regions Persia, Athens, and Sparta, among others.

First, he got in between two brothers – Persian King Artaxerxes II and his younger sibling Cyrus the Younger (a price he will pay with his life to their mother Parysatis). After first betraying Cyrus, and later killing him at the Battle of Cunaxa, Tissaphernes pursued Xenophon and his Ten Thousand men in retreat with a vast force. We already said that Xenophon brought his men home, but Tissaphernes became an enemy of both Sparta and Athens because of all the events mentioned above.

Now, it’s important to remember at this moment that Athens and Sparta were not particularly friendly to each other… indeed, they were sworn enemies. Despite this, Xenophon of Athens (as he was called) did not hide his profound admiration for Sparta and Spartan leaders (Agesilaus II and Lysander, in particular).

Coinage of Phokaia, Ionia, circa 478-387 BC. Possible portrait of Satrap Tissaphernes, with satrapal headress.

But Tissaphernes was the main reason why Xenophon came to respect the military wisdom of the Spartans. While he was seeking refuge from Tissaphernes, he noticed the respect Spartan leaders had for one another while successfully fighting the Persian satrap in Asia Minor.

So much, in fact, that he mentioned them extensively in his works Anabasis, Agesilaus, Polity of the Lacedaemonians, and Hellenica.

Excerpt from Agesilaus, Xenophon:

«It would be hard to discover, I imagine, anyone who in the prime of manhood was as formidable to his foes as Agesilaus when he had reached the limit of mortal life. Never, I suppose, was there a foe-man whose removal came with a greater sense of relief to the enemy than that of Agesilaus, though a veteran when he died. Never was there a leader who inspired stouter courage in the hearts of fellow-combatants than this man with one foot planted in the grave. Never was a young man snatched from a circle of loving friends with tenderer regret than this old graybeard.»

Spartan King Agesilaus

Excerpt from Hellenica, Xenophon shows the relationship between the Spartan Rulers, in particular the king Lysander and king Agesilaus:

“But here was Lysander back again. Everyone recognized him and flocked to him with petitions for one favour or another, which he was to obtain for them from Agesilaus. A crowd of suitors danced attendance on his heels and formed so conspicuous a retinue that Agesilaus, anyone would have supposed, was the private person and Lysander the king.«All this was maddening to Agesilaus, as was presently plain. As to the rest of the Thirty, jealousy did not suffer them to keep silence, and they put it plainly to Agesilaus that the super-regal splendor in which Lysander lived was a violation of the constitution.«So when Lysander took upon himself to introduce some of his petitioners to Agesilaus, the latter turned them a deaf ear. There being aided and abetted by Lysander was sufficient; he sent them away discomfited.«At length, as time after time things turned out contrary to his wishes, Lysander himself perceived the position of affairs. He now no longer suffered that crowd to follow him and gave those who asked him help in anything plainly to understand that they would gain nothing, but rather be losers, by his intervention.«But being bitterly annoyed at the degradation put upon him, he came to the king and said to him: “Ah, Agesilaus, how well you know the art of humbling your friends!” “Ay, indeed,” the king replied: “Those of them whose one idea it is to appear greater than myself. If I did not know how also to requite with honour those who work for my good, I should be ashamed.”«And Lysander said: “Maybe there is more reason in your doings than ever guided my conduct” adding, “Grant me for the rest one favour, so shall I cease to blush at the loss of my influence with you, and you will cease to be embarrassed by my presence. Send me off on a mission somewhere; wherever I am I will strive to be of service to you.”

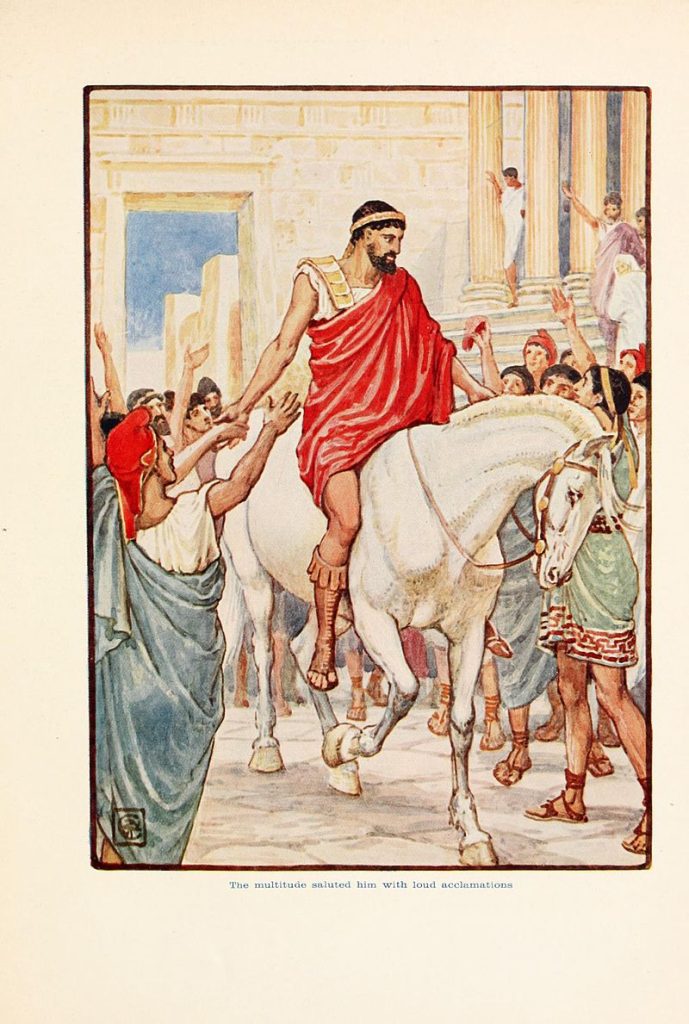

The multitude saluting Lysander with loud acclamations.

Apostle of Socrates

From Xenophon’s excerpts on Sparta, as well as from other historical facts, we must understand two things before we can go to one of the most important roles Xenophon played in the history of humankind.

One, Athens was on its decline and the trial of Socrates only illustrated how Athens represented, or rather failed to represent, a pedestal of democracy. Sparta, on the other side, as Xenophon underlines “even though among the most thinly populated of states, was evidently the most powerful and most celebrated city in Greece. And I fell to wondering how this could have happened. But when I considered the institutions of the Spartans, I wondered no longer.”

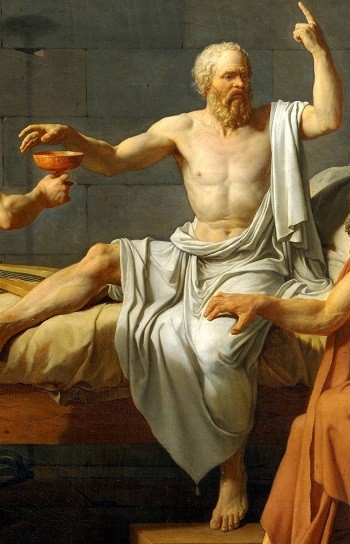

The Death of Socrates

Second, Sparta was admired as a whole, envied because of its unity. Athens, however, produced magnificent individuals, who were free to question, write, and influence one another, even if it meant an inevitable fall in the end, as Socrates clearly demonstrates.

Thus, it is very important to appreciate this polarity both in general and with regards to Xenophon specifically. Xenophon had the opportunity to perceive both sides and thus produce works that reflect a wider, more honest, spectrum of Ancient Greece.

Thalatta! Thalatta! (The Sea! The Sea!) — painting by Bernard Granville Baker, 1901 – A famous scene from Xenophon’s works

Xenophon’s admiration for Sparta was only equalled by his love for his mentor, the first moral philosopher of the Western ethical tradition of thought, Socrates.

Memorabilia, Apology, Oeconomicus, and Symposium were all Xenophon’s gospels to Socrates. He admired his teacher very much (along with fellow protege Plato). So much so that some conjecture that Socrates would not have been sentenced to death if Xenophon had been in Athens instead of on a military expedition in Persia.

Per Diogenes Laërtius, a biographer of the Greek philosophers:

“They say that Socrates met Xenophon in a narrow lane, and put his stick across it and prevented him from passing by, asking him where all kinds of necessary things were sold. And when he had answered him, he asked him again where men were made good and virtuous. And as he did not know, he said, ‘Follow me, then, and learn.’ And from this time forth, Xenophon became a follower of Socrates.”

Drawing of Socrates

Xenophon’s Works

Xenophon was greatly prolific. Of the 14 works we know of, they can be broadly categorized into three categories. His ‘Historical and biographical’ works include: Anabasis, Cyropaedia, Hellenica, Agesilaus, and Constitution of the Lacedaemonians.

Next are his ‘Socratic’ works, which are: Memorabilia, Apology, Oeconomicus, and Symposium. Finally his ‘other’ works are: Hiero, On Horsemanship, Hipparchikos, Hunting with Dogs, and Ways and Means.

Xenophon’s Death

There is no firm record on how Xenophon spent his last days. There is one version of him being exiled (or self-exiled) from Athens to Scillus and later in Corinth. It is estimated that he died circa 354 BC.

It is recorded that he had two sons, Gryllus and Diodorus, who fought at the Battle of Mantinea as members of the Athenian army.

Xenophon, Aphrodisias Museum

Xenophon’s Achievements and Legacy

Aside from what we have previously mentioned, it is important to emphasize that Xenophon was a sort of practical philosopher. This is what made him a successful military strategist, leader, soldier, politician, poet, and historian.

His Anabasis was used as a field guide by none other than Alexander the Great during the early phases of his expedition into Persia. Moreover, Memorabilia had a huge and important impact on the Founding Fathers of the United States, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, in particular. Clearly Xenophon’s influence on mankind can not be overstated.

One comment

Almost afraid to leave a comment, I have just started at the age of 60 studying the ancient classics. I have read and studied much about different individuals, Now I am trying to connect the dots and see the bigger picture. This explains so much, thank you.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.