By Benjamin Welton

“Etruria is the originator and mother of all superstition.”

This was stated by Arnobius the Elder, a Christian apologist living during the reign of the Roman emperor Diocletian, who was a great persecutor of Christianity.

By “superstition” he meant the Etruscan religion, which, along with Greek, was the primary influence on Roman worship. Etruscan religious texts even outlived the general use of the Etruscan language. It was this regionally unique belief system that is whispered to have subtly influenced the early Christians of Italy.

Even today, while the rest of Italy is known for the widespread practice of folkloric rituals, the former lands of the Etruscans eclipse all in terms of superstitions and tales of witchcraft.

During the reign of the unknown “Monster of Florence” (1968 -1985), many Florentines, who inhabit the Etruscan heartland of Tuscany, took seriously the rumors that the serial killer was part of a wider network of Satanic witches and warlocks. Even the highly-publicized trial of Amanda Knox and Raffaele Sollecito in the ancient Umbrian city of Perugia (which the Etruscans called Perusna) included official accusations of sexualized Satanic rites.

Despite the vast distance of time, Etruria, it seems, still remains the mother of superstition – both in the habits of the people… and their mysterious origins.

Nowadays, Etruria corresponds with the Italian states of Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio. Its name comes from the Greek and Latin word for its inhabitants – the Etrusci, though they are known today as the Etruscans.

For hundreds of years they were the predominate power in Italy and bequeathed to the later Roman Republic not only its founding myth (the Greco-Etruscan house of Tarquin and the legendary kings of Rome), but also much in the way of religion and scholarship. The Etruscans left an indelible mark on Roman history, and therefore a mark on the entirety of Western civilization.

Yet, despite this legacy, their language and origins are still up for debate.

Many people maintain that the Etruscans were most likely an Eastern people transplanted to northern Italy due to a famine. The Greek historian Herodotus, who often interspersed mythology inside of nominal histories, wrote that the Etruscans originally came from Lydia, in Anatolia. Ancient Lydia was part of the Ionian Greek orbit, and the Indo-European Lydians, who are most commonly known to mythology enthusiasts by the Lydian king Croesus, were participants in the semi-historical Trojan War.

According to Herodotus (and later echoed by Virgil in the Aeneid), the forefathers of the Etruscans were led out of Lydia by the brothers Tyrrhenus and Tarchon. After arduous sailing, the siblings and their people eventually settled in northwestern Italy near the sea that still bears their name – the Tyrrhenian Sea.

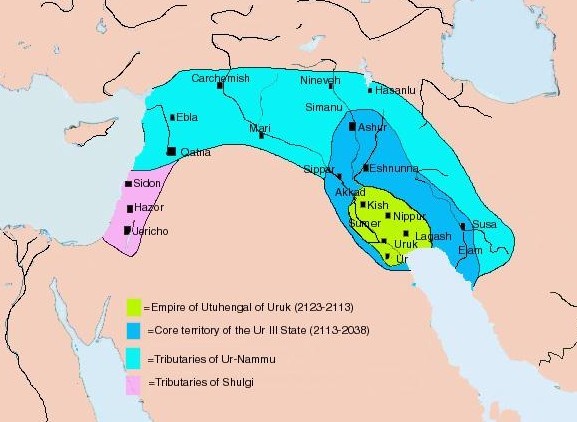

During the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, the Etruscans established a league of twelve cities, which became the vehicle for greater Etruscan expansion in the Mediterranean. They were able to increase their power north, past the Po River, and south to Campania. Along the way, the Etruscans not only fought the Alpine Gauls, but also laid the groundwork for the eventual city of Rome.

In this Anatolian theory, Etruscan civilization can best be compared to Norman England. After William, Duke of Normandy’s conquest of England in the 11th century, a process of “Normanization” occurred throughout Great Britain. Consequently, the French language began to take root in the native English one. Still, throughout the many years of Anglo-French rule in Great Britain, the local, non-royal population remained overwhelmingly either Anglo-Saxon or Celtic in origin.

Using this analogy, a small minority of Anatolian Lydians would have been at the top of Etruscan life in terms of politics, the arts, and religion, while leaving the rest of the populace indigenous.

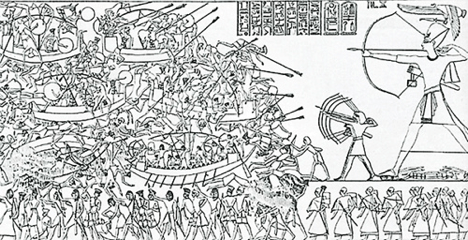

(IMAGE: A recreation of the Egyptian relief showing Ramesses III battling the Sea Peoples in the Nile Delta)

This population model is just theory… and with regards to the Etruscans, it’s far from the only one.

Some Ancient Greek authors believed that the roots of the Etruscans lay with the Pelasgians, the “Sea People” of the island of Lemnos. During the late 19th and early 20th dynasties of Egypt, the “Sea Peoples” were a loose confederation of Indo-European pirates from all across the Mediterranean responsible for attacking the Egyptian Empire in the Levant, as well as the Hittite Kingdom in Anatolia.

This chaotic period is the source of much speculation about the ancient world, from the possible Greek origins of the Philistines, to the founding of potentially Indo-European kingdoms and colonies all throughout the Near East. The “Sea Peoples” came out of nowhere, and just like that, they were gone. Few historical accounts record much about them after the naval Battle of the Delta, when Ramesses III soundly defeated them, sometime in 12th century BCE.

Some have speculated that the Ancient Greek classics of the Iliad and the Odyssey hold clues to the prolonged settlement of the Mycenaean Greeks in the Near East. Meanwhile, others have maintained that this so-called “Bronze Age Collapse” not only resulted in the Indo-European colonization of certain parts of the Near East, but also in a reverse colonization, whereby Anatolian and even Semitic peoples left their war-torn homes in order to settle in Europe.

Supposedly, the Etruscans were part of this East-to-West migration.

Supporters of this theory tend to point out the clear Eastern influences in Etruscan art. The Regoloni-Galassi tomb in the ancient city of Caere (today’s Cerveteri) is an Etruscan family tomb that is most commonly dated to the 640s BCE.

(IMAGE: Golden griffins taken from the Regoloni-Galassi tomb)

The art contained within the tomb shows motifs and images that are more commonly associated with the “Orient,” from Assyrian lions to Egyptian Sphinxes and scarabs.

For many, this showcases the fact that the Etruscans were culturally Eastern. For most scholars, however, this is an indication of Etruscan “Orientalizing,” or the intentional fusion of Greek and Eastern Mediterranean culture with the local Etruscan one. There is a historical precedent for this as well; the Archaic Age in Greece, for instance, saw a widespread injection of Egyptian, Persian, and Phoenician art and culture.

The “Orientalizing” theory rejects the idea that the Etruscans were Anatolian or Aegean colonists. Instead, it promotes the idea that Etruscan civilization was autochthonous, or indigenous to northwestern and central Italy. This theory is more than likely the correct one, and most scholars agree that the Etruscans were Italian through and through.

Still, the major roadblock towards complete assurance is the mystery of the Etruscan language, which is a language isolate with only a paltry few documents left.

Etruscan clearly influenced Latin (the name Rome comes from the Etruscan “Ruma”) and its alphabet may have even been the foundation of the Runic alphabet of the pre-Christian Germanic peoples. The Roman subjection of the Italian peninsula, however, caused the sharp decline of not only the Etruscan language, but also its Raetic cousin.

By the first millennium AD, the Latin Romans had gutted the Etruscan language. With the coming of Christianity, Etruscan civilization was effectively destroyed and the rolling hills of Tuscany went back to holding their vestigial secrets.

Modern Etruscology is a fascinating sub-discipline of history. Much like Egyptology, which has often been the fodder for Hollywood glamorization, Etruscology has an air of mystery that is hard to ignore. The many legends swirling around the Etruscans make them one of history’s more suggestive groups, while their clear importance, but lack of concrete evidence, makes them and their civilization all the more open for inference.

It’s easy to write magic into places where the facts haven’t yet permeated the popular imagination. As the eminent Italian archeologist, Massimo Pallatino, once wrote in the introduction to D.H. Lawrence’s Etruscan Places:

“I don’t think there is any other field of human knowledge in which there is such a daft cleavage between what has been scientifically ascertained and the unshakeable beliefs of the public…”

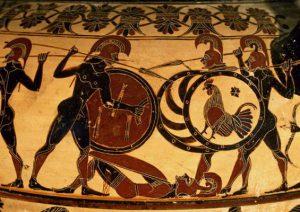

The Spartans, for whatever reason, wrote next to nothing of their culture, or if they did it has been lost. Almost all of what we know of the Spartan society comes from outside observers. And while many ancient authors make mention of the militaristic Lacedaemonians, it is Xenophon, a pupil of the philosopher Socrates, who associated most with the Spartans and, as a consequence, wrote extensively of the Spartan culture in his essay “The Polity of the Lacedaemonians”.

The Spartans, for whatever reason, wrote next to nothing of their culture, or if they did it has been lost. Almost all of what we know of the Spartan society comes from outside observers. And while many ancient authors make mention of the militaristic Lacedaemonians, it is Xenophon, a pupil of the philosopher Socrates, who associated most with the Spartans and, as a consequence, wrote extensively of the Spartan culture in his essay “The Polity of the Lacedaemonians”.

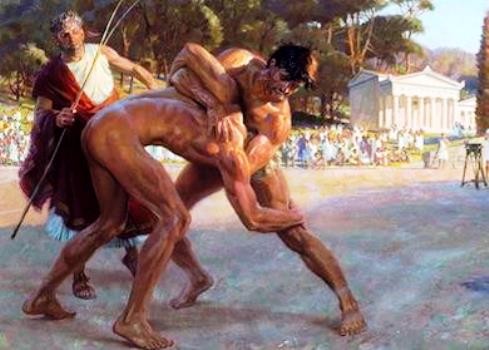

The actual training of the Spartan youth was brutal, focusing on cultivating skills such as fighting, stealth, pain tolerance, as well as dancing, singing, and developing loyalty to the Spartan state. With the exception of the first born sons of the ruling houses, the young boys of Sparta entered into this training curriculum, known as Agoge, starting at the age of seven. They would train in the art of fighting for decades, eventually becoming reserve infantry at the age of eighteen, regular foot soldiers at the age of twenty, and eventually full Spartan citizens, with the rights to vote and hold office, at the age of thirty.

The actual training of the Spartan youth was brutal, focusing on cultivating skills such as fighting, stealth, pain tolerance, as well as dancing, singing, and developing loyalty to the Spartan state. With the exception of the first born sons of the ruling houses, the young boys of Sparta entered into this training curriculum, known as Agoge, starting at the age of seven. They would train in the art of fighting for decades, eventually becoming reserve infantry at the age of eighteen, regular foot soldiers at the age of twenty, and eventually full Spartan citizens, with the rights to vote and hold office, at the age of thirty. Additionally, the boys were given only one garment of clothing. They were regularly subjected to extreme cold, all while only wearing a single cloak. In this way the young soldiers would gain a tolerance to the elements.

Additionally, the boys were given only one garment of clothing. They were regularly subjected to extreme cold, all while only wearing a single cloak. In this way the young soldiers would gain a tolerance to the elements.