By Katherine Smyth, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

If you think you know the story of Circe, the witch of Aeaea and the seducer of the hero Odysseus, think again. There’s more to her story than is widely publicized or acknowledged, but to understand how Circe became one of ancient Greek mythology’s most notorious women you have to go back to the beginning of time.

Time before men

Back before men were even a twinkle in Prometheus’ eye, Circe was born to Helios, a son of the Titans Hyperion and Theia, and brother to the goddesses Selene and Eos. She is also cousin to Zeus, the King of the Olympians. So you could say that Circe was born into quite a noble family. A granddaughter of at least two Titans and related to the sun, moon, and dawn, big things should have been laid out for her from birth.

Except, that’s where her ancestry gets indistinguishable and a little problematic. One possibility is that she was a daughter of Hecate, an ancient deity that pre-dates the Olympians and whom Zeus honored above all, at least according to Hesiod.

Circe’s other matrilineal probability is Perse, an Oceanid nymph and one of several thousand daughters by the Titans Oceanus and Tethys. Perse is also the mother of Aeetes, keeper of the Golden Fleece; Perses who was killed by his niece Medea; and Pasiphae the Queen of Crete. What makes her lineage a bit tangled is that Perse can also be closely identified with Hecate, a virgin goddess who had no regular consort. Hecate is also listed in some traditions as the mother of Scylla, who you’ll be introduced to shortly.

Les Oceanides Les Naiades de la mer. Gustave Doré, 1860s

Here enters Circe, the granddaughter of four Titans, niece to the moon and sunrise, blessed by the golden rays of her father, but lacking all the enticements and goddess-given beauties of her nymph mother. Yes, according to myth, when Circe was born she was not what was expected. Instead of being attractive with willowy limbs and a melodic voice, like the other nymphs, Circe lacked all the usual charms of a seductress. Instead, she was short, dark, and sounded like a squawking bird. This is where her name stems from, specifically the Latinized form of Greek Κιρκη (Kirke), which possibly meant “bird”.

The making of a witch

Growing up, Circe was all too aware of her shortcomings. Unlike her sister Pasiphae, she would not be married off to a mortal to rule over humans and bear mythological beasties (see my previous article on the Minotaur). Also, unlike her brothers Aeëtes and Perses, she was denied a kingdom of her own. So, she stayed with the throng of Titans and Olympians and kept to herself.

John William Waterhouse’s Sketch of Circe (c. 1911–1914)

It was during this isolation that her gifts were developed and honed. Whether it was due in part to her maternal parentage, or whether it was her fate, Circe’s magical abilities manifested into both potion making and spell casting. Circe quickly gained a reputation for trickery, being ill tempered, and adept at casting spells on those who ridiculed and mocked her. Would-be lovers who spurned her, or essentially anyone who showed her any disrespect would find themselves transformed into an animal without the slightest effort on her behalf.

According to some versions of her story, it is this crafting of the supernatural that ultimately led to her exile on the remote, and fictitious, island of Aeaea – thought to be located off the southern coastline of Italy, about 100 kilometers from Rome. She was sentenced to an eternity on the island as punishment for practicing witchcraft on her fellow nymph, Scylla. Circe had fallen in love with Glaucus, a sea-god, who as the Fates would have it became besotted with Scylla. When Circe’s advances and attempts at seduction failed miserably, she became incensed and in a jealous rage, Circe poisoned the water where Scylla bathed. As a result, the hideous monster was born and Circe’s fate was sealed: life-long banishment from her immortal home and family.

Circe and Scylla in John William Waterhouse’s Circe Invidiosa (1892)

However, it’s here on the island of Aeaea that Circe’s greatest claim to fame is formed. Odysseus, King of Ithaca, war hero of the Iliad and doomed sea captain was guided to Circe’s island as part of his journey back home. Fortunately for him, Hermes told him what to expect, and how to elude her spells and potions. So, when Odysseus landed on the shores of Aeaea, and half of his men met with the enchantress’ wrath, her immense powers were futile against him thanks to an herb called moly.

A different fate perhaps?

Angelica Kauffman’s painting of Circe enticing Odysseus (1786)

Instead of harming her for attacking his men, Circe and Odysseus’ relationship took a different turn. Once Circe realized that she was unable to defend herself against Odysseus’ advances, she instead became his lover for the rest of his time on Aeaea. Now, some would say that bedding Odysseus was the act of a woman whose plans been defeated, that when she knew she could not turn him into an animal – as she had done to so many other mortals and fools alike – she instead used sex to her advantage. But is this truly the case, or did she admire and deeply care for him as a result of his intellect and wit?

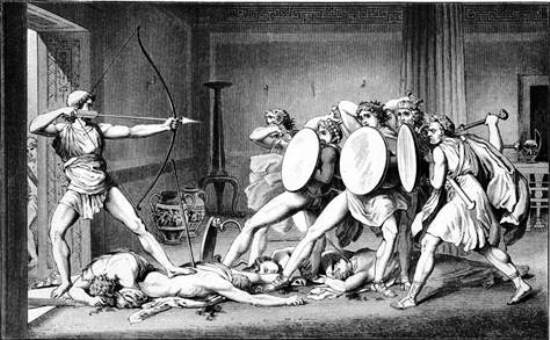

This same story that paints her as being malicious glosses over the fact that she opened her home to a host of rude and selfish men. That for a year Circe fed, housed, and clothed them. Circe offered hospitality to those who had sought to violate, harm and destroy her, and the parallel between her generosity and that of Penelope’s should be remembered. What was Odysseus’ response to his wife’s hospitality towards ‘the Suitors’? He massacred them, as a victorious and righteous hero and husband. Yet Circe is condemned for protecting herself.

Odysseus’ killing of the suitors

During their union, Circe and Odysseus brought about the creation of three sons; Agrius, Latinus, and Telegonus, all of whom would become famous like their father. However, it is Telegonus, the youngest, who would become the ill-fated offspring that kills his father. Ironic as it fulfilled Odysseus’ fate, a foreshadowed story that he’d been warned of years before. Divine punishment perhaps, for the wrongs the hero committed?

As Odysseus’ time on Aeaea came to an end, it was Circe who gave him valuable insight on how to sail safely home from Aeaea, and how to avoid the island of the Sirens, along with steering clear of both Scylla and Charybdis. Circe also gave Odysseus information on how to avoid punishment should they land on Thrinakia, the home of her grandfather, Hyperion’s cattle. Unfortunately for Odysseus, his crew ignored Circe’s advice and their destruction was assured as retribution, all saving the captain.

Although Odysseus survived the punishment that killed his men, the story of Circe and Odysseus does come to a sticky end. Upon discovering who his father was, Circe sent her youngest son to find his father before returning to her. Unfortunately, that’s where the Fates stepped in, and through a terrible accident, Odysseus was slain. As foretold, Odysseus was killed by his son, just not the one he expected. Where he feared it would be his beloved son Telemachus, it was instead Telegonus, the boy he never met who sought only his father’s love and acceptance. The next time Circe would see her son was when he returned to Aeaea with Telemachus, Penelope, and Odysseus’ body.

Odysseus and Penelope. Painting by Francesco Primaticcio (1504-1570). Photo: Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio.

Hesiod’s Theogony indicates how Circe’s fate may have played out from this point. Upon the return of Telegonus, they bury Odysseus’ body and then Circe makes the other three into immortals. Madeleine Miller, the author of Circe, expands on this with another possibility that Penelope and Telegonus become lovers and remain on Aeaea as immortals. After a lifetime or so together Circe and Telemachus give up their immortality to die, whereupon the story is completed and fades into time immemorial.

Circe in History

Since the days of ancient Greece, Circe’s name has been synonymous with witchcraft, seduction, and deception. She’s been depicted in paintings tempting Odysseus, casting spells over his men, and practicing her dark arts to lure wayward men and punish them.

Artists like Frederick S. Church have portrayed her in gentler tones, whilst John William Waterhouse’s Sketch of Circe displays her intelligence, wit, and her animalistic companions. Are these the only artists to have presented her in art? No, Circe’s been popping up in paintings, drawings, and illuminations for hundreds, if not thousands of years. She’s been both muse and subject for many, but sadly she’s almost always seen as a villain.

Frederick S. Church’s painting of Circe

Was Circe really to blame?

This is popular opinion and aids the narrative that permeates much of classical mythology and history, and fulfills exactly what Steven Sora (The Triumph of the Sea Gods) and Sigmund Freud (the Madonna-whore complex) refer to in their works. It is the old trope of women interfering or causing good men to go bad, and Circe’s story is merely one such example.

But Circe is, at least, in fine company. She sits quite comfortably alongside the likes of Helen of Troy, Pasiphae, Clytemnestra, Hera, Hecate, and a host of other ladies who’ve all been labelled as troublesome. Perhaps it’s finally time to view Circe in another light, that of being considerate and generous, intelligent, clever, headstrong and independent.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.