By Van Bryan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

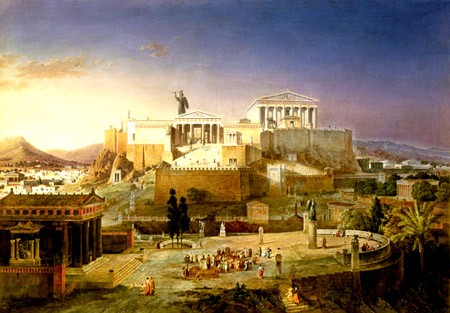

Athens in its Golden Age

Recently, your editor asked a question…

Is nationalism “good”?

How interesting, we thought to ourselves. Immediately, hand went to chin. We furrowed our eyebrows in earnest ponderance.

Some questions stay with you, dear reader. Like a sore on the roof of your mouth that would go away if only you could stop tonguing it, but you can’t.

Today, we pursue the topic…

Classical Nationalism

The ancients had plenty to say on the topic of nationalism. After the Greco-Persian wars of the early fifth century, the unlikely expulsion of the Achaemenid Persian empire must have seemed like a miracle. Here, a plucky band of Hellenic tribes had expelled what was the reigning superpower of the ancient world.

“Leonidas at Thermopylae” by Jacques Louis David. All 300 Spartans along with the Helot slave warriors fought to their deaths. Persia won the battle, but lost the war.

A little chest-pumping was in order. And the idea of Greek superiority was established in the mind of the allies. After all, what could account for such a startling upset? Dumb luck? Superior planning? Arrogance and stupidity on the part of the Persians?

Negative…

As Aeschylus shows in his The Persians, the Greeks believed it was their piety that won the day. Their superior faith in the gods smote the Persians and drove them back across the Aegean.

Greek and Persian warriors depicted fighting on an ancient kylix. 5th century BC. (Public Domain)

There misery waits to crush them with the load

Of heaviest ills, in vengeance for their proud

And impious daring; for where’er they held

Through Greece their march, they fear’d not to profane

The statues of the gods; their hallow’d shrines

Emblazed, o’erturn’d their altars, and in ruins,

Rent from their firm foundations, to the ground

Levell’d their temples; such their frantic deeds,

Nor less their suff’rings; greater still await them;

Need more evidence?

The term “barbarian” comes from the Greek word “barbaroi.” It literally meant a non-Greek.

Edith Hall writes in Inventing The Barbarian:

Greek writing about barbarians is usually an exercise in self-definition, for the barbarian is often portrayed as the opposite of the ideal Greek. It suggests that the polarization of Hellene and barbarian was invented during the early years of the fifth century BC, partly as a result of the combined Greek military efforts against the Persians.

In other words, the classical Greeks didn’t just believe themselves great. They believed themselves SUPERIOR to the “barbarian” tribes.

Depiction of Persian warriors, most likely the Immortals.

Ah, but now the stage is set. Let’s return to your editor’s question. Is nationalism GOOD?

Athens First

Flash forward a few decades. It’s the late fifth century and the Athenians are engaged in bloody struggle, The Peloponnesian War. The opponent this time is the ignoble Spartans. After years of fighting, the Athenians are weary. Heavy losses have mounted.

Writes Themistocles, quoting Pericles:

For we have compelled every land and every sea to open a path for our valor and have everywhere planted eternal memorials of our friendship and of our enmity. Such is the city for whose sake these men nobly fought and died; they could not bear the thought that she might be taken from them; and every one of us who survive should gladly toil on her behalf.

Translation: sorry about your sons and husbands. But it was all for a good reason. Look at all our stuff! Now get back out there, champ.

Pericles’ Funeral Oration was a famous part in “The History of the Peloponnesian War”.

Pericles’ Funeral Oration by Philipp Foltz (1852)

What patriotic hearts must Pericles have stirred to action? How many sons and husbands would take up the just and noble cause of polis. We don’t know precisely. But certainly the goddess Athena smiles up on the city that bears her name. She would see patriotic Athenians to victory. Right?

Not so much…

The Athenians would fall to the Spartans in 404 BC. Their walls would be torn asunder. Democracy, which the Athenians are credited as being the first to give it a go—would be suspended. The Spartans, had they wished, could have razed the city, killed the men, enslaved the women, and nicked all the imperial booty for themselves.

Fortunately, that did not come to pass. Athens would suffer under the tyrannical rule of the “Thirty Tyrants” for a time. But democracy was eventually restored. Life went on.

Vase depicting tyrannicide

But had the city been burned, the Athenians would have had only their vain nationalistic pride to blame…

Lies and Myths

To your editor’s question. Nationalism. Good? Bad?

Neither.

The nationalism of the ancient world was a convenient myth. Like the Olympians themselves, it could be neither proven nor disproven. The inherent greatness of Athens was neither true nor untrue. But it was useful. It was useful to Athenian generals and politicians who had a vested interest in expanding their fledgling empire into the Aegean immediately following the conclusion of the Greco-Persian war.

The imperial swag flooded the city from conquered nations. The status of well-placed Athenian elite was elevated with each conquest. And why not? The gods are with us!

Poseidon and Athena battle for control of Athens – Benvenuto Tisi da Garofalo (1512). ( Public Domain )

It’s not a new idea to say that a society tells itself myths. Plato was well aware of it.

Writes Plato in The Republic:

Thus it is that the stories we tell our children must be morally uplifting, and some of the myths are not. Therefore we must winnow the myths, editing them, and, in some cases, censoring aspects of them.

This idea is not even an ancient one.

Large numbers of strangers can cooperate successfully by believing in common myths. Any large-scale human cooperation – whether a modern state, a medieval church, an ancient city or an archaic tribe – is rooted in common myths that exist only in people’s collective imagination.

The inherent greatness of the classical Greeks was a myth. It was an apparition that existed collectively in the minds of a people. Once you understand cultural mythmaking, you can’t not see it.

“Making the world safe for democracy” was a myth. So is “Workers of the world, unite!” So is MAGA.

The nationalistic myths of the Greeks allowed them to rally behind a cause and expel a foreign empire. But it also drug the Athenians and Spartans into an intractable war. A society’s ability for nationalistic mythmaking inspired the erection of the Parthenon. It also gave rise to Auschwitz.

Let us then return to your editor’s question.

Is nationalism “good”? No.

But it’s not “bad” either. It’s useful.

To whom? That’s for you to answer…

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.