By Nicole Saldarriaga

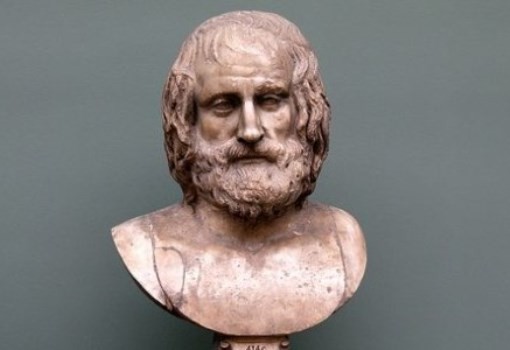

There’s a reason Euripides is often called the “people’s poet.” Though his plays were not the most popular in their own time, after his death they were soon recognized for their incredible attention to character.

Euripides, the People’s Poet

Euripides was able to take people on the outskirts of society—slaves, women, illegitimate children—and give them complicated psychologies and desires in a way that no tragedian was ever able to do before. One of his most famous plays, the Hippolytus, is a great example of this—by telling a story that seems fairly uncomplicated on the surface, Euripides is able to give us a glimpse into the complicated psyche of an illegitimate man who desperately craves legitimacy, and ultimately show us the intricate relationship between love and law.

Hippolytus begins with the appearance of the goddess Aphrodite on the stage. She introduces the audience to the major conflict of the play: Hippolytus, the illegitimate son of Athens’ King Theseus, has severely insulted Aphrodite by rejecting her and erotic love altogether in favor of a chaste life as a devotee of Artemis. As punishment, Aphrodite causes Theseus’ wife, Phaedra, to be overcome by a desire for her stepson—so that, once Phaedra’s unlawful attraction is revealed, Theseus will kill Hippolytus.

Aphrodite’s plan succeeds spectacularly: when Phaedra’s nurse, in an effort to save her mistress (who, rather than admit her shameful love, is attempting to kill herself by starvation) reveals Phaedra’s secret to Hippolytus, and the horrified Hippolytus angrily rejects it, Phaedra’s intense shame leads her to hang herself—but not before leaving a note for Theseus in which she claims to have been raped by Hippolytus.

The outraged Theseus uses one of three wishes given to him by Poseidon to curse his son, and as Hippolytus flees into exile, Poseidon sends an enormous bull thundering out of the sea, which startles Hippolytus’ horses; the man is thrown from his chariot, though he remains tangled in the reigns, and the horses drag him to his death against the rocks.

More Than Meets the Eye…

This brief summary only hints at the complexities hidden beneath the surface-story. To plumb these depths and reveal the underlying tension between eros (erotic love) and nomos (law or custom), we must take a closer look at Hippolytus and Phaedra.

When Hippolytus first appears, he is just returning from a hunt, and his first order of business is to give reverence to Artemis. “For you, dear Lady, I bring this garland, this lovely chain of flowers,” he proclaims as he stands before her statue and altar, “from a virgin meadow…virgin it is, and in summer the bees frequent it, while Purity waters it like a garden.”

Euripides wastes no time in showing the audience that Hippolytus not only esteems the goddess, but also the very concept of virginity—above all else. What seems like every time he is on stage, Hippolytus references his virginity and his commitment to chastity in some way—it is clear that he holds tightly to the ideal and to the holiness he hopes to gain from his chastity.

Why is Hippolytus so determined to reject eros—an erotic longing which, according to Phaedra’s nurse, is willed by the gods and cannot be withstood without a certain amount of arrogant presumption?

“Euripides wastes no time in showing the audience that Hippolytus not only esteems the goddess, but also the very concept of virginity—above all else.”

Even his own attendants attempt to warn Hippolytus that his rejection of Aphrodite is disrespectful and dangerous, but Hippolytus is resolute, responding simply with a sardonic “I don’t like deities who are marvelous after dark.” The blatant cynicism of that statement is our first clue in understanding Hippolytus’ character: his rejection of eros is largely related to the deep seated feelings of hate and anger which he holds in his heart.

Hatred of Women?

It would be all too easy to simplify Hippolytus’ hatred by calling it a hatred of women—his most famous speech, after all, delivered after the nurse informs him of Phaedra’s amorous desires, begins “Zeus! Why did you let women settle in this world of light, a curse and a snare to men?” and ends with “Let people say I am always harping on the same theme. Still I shall never tire of hating women.” His hatred of women is very real—however, to claim that it is the only reason for his rejection of eros is to over-simplify a much more complex decision which very likely can be traced back to Hippolytus’ identity as Theseus’ son.

Desperate for Legitimacy

Hippolytus’ history is not complicated to understand (in fact, stories like his seem all too common in Ancient Greek history and mythology), although it’s likely to have had some complicated consequences on Hippolytus’ character.

Hippolytus’ mother, named Hippolyta, represents a dark side to Theseus’ history as a legendary hero and upright citizen: she is one of many women whom he kidnapped and later deserted. While Hippolyta’s ultimate fate is unclear, we do know that she bore Theseus a son, and that Hippolytus grew up defined by his status as a bastard child of the king. His behavior, particularly his vow of chastity and hatred of women, openly points toward his resentment of his illegitimacy.

Hippolytus is dragged to his death

In striving always to be pious—a shining example of devotion to the gods—Hippolytus is showing an obsession with the law, with nomos. In rejecting eros—the erotic, the feminine, the familial—he is attempting to achieve a perfect lawfulness, uncomplicated by the powerful, natural force that often causes people (like Phaedra, like Hippolytus’ own father) to break the law and destabilize the city by undermining laws of inheritance and succession. He is, in essence, avoiding the force that leads to the birth of illegitimate children (who, it is important to note, are basically forced to live outside the law. Ancient Greece stripped illegitimate children of many if not most rights of citizenship).

Hippolytus’ desire to avoid that natural force of eros is perhaps most visible in his famous speech about women. He says to Zeus:

|

If you wished to propagate the human race you should have arranged it without women. Men might have deposited in your temples gold or iron or a weight of copper to purchase offspring, each to the value of the price he paid, and so lived in free houses, relieved of womankind.. |

|

|

Hippolytus dreams of a city in which love, marriage, and sex are unnecessary. Familial ties are based solely on an exchange of goods.

“Hippolytus is, in essence, avoiding the force that leads to the birth of illegitimate children.”

As classicist and philosopher Seth Benardete put it in his The Argument of the Action, “Hippolytus…judges nature in light of the law rather than law in light of nature. His scheme depends on keeping the law of private property: the abolition of nature is better than any cancellation of the law.” Hippolytus wants a world of perfect law without nature—nomos without eros. What he does not see, of course, is that this is an utterly impossible dream.

Nature, represented in the family, also represents a kind of paradox: it is both a threat to the city, and an absolute necessity to the city. Though loyalty to your family can certainly undermine your adherence to the law (love and loyalty to one’s mother, for example, could lead one to break the law if it meant defending or avenging her), the city is also built upon its families, because families provide the city with citizens. It’s for this reason, more than anything else, that marriage laws were formed in Ancient Greece—adultery was considered unlawful, of course, and in a certain way, marriage was expected of every law-abiding citizen, so that the population wouldn’t die out and the city would be kept going. Eros may be a threat to nomos in some ways, but they are also inextricably linked.

The goddesses in the play themselves function as examples of that link. While it may seem that they are at odds with each other and not on the friendliest of terms (in fact, at the end of the play Artemis promises to punish one of Aphrodite’s followers as revenge for the death of Hippolytus), they are also connected.

“Eros may be a threat to nomos in some ways, but they are also inextricably linked.”

Artemis is the goddess of virginity (and she becomes, for Hippolytus, a kind of representation of self-control and lawfulness), but she is also the goddess of the hunt, and the hunt is a perfect symbol for erotic desire—it is the chase, the constant longing to obtain the object of obsession (this is particularly interesting in regards to Hippolytus, who is an avid hunter. One has to wonder whether his love of the hunt is a kind of displacement of his repressed erotic feelings).

Aphrodite is the goddess of love, and is associated with a certain amount of eroticism, but she is also (some would say first and foremost) considered the goddess of lawful marriage, and in this way she is important to the health of the city. Thus, the goddess of nomos (for the purposes of this play) also holds within her character an aspect of eros, and the goddess of eros holds an aspect of nomos. Aphrodite and Artemis are, in some ways, indecipherable from each other.

With Aphrodite’s relationship to the law in mind, we can see the punishment of Hippolytus in an entirely new light. Hippolytus, by refusing eros, is refusing to get married, and is thus disrespecting not only nature, but also the laws of the city (in essence it is a vicious circle: the man who grew up outside the law, in a desperate attempt to live within that law, continues to alienate himself from it).

In this case, though it may seem over-harsh to modern readers, Hippolytus deserves his punishment—his punishment is in keeping with the law.

Phaedra, Hippolytus’ step-mother, also seems to be caught in the same vicious circle of lawfulness which ensnares Hippolytus. When we first see Phaedra, we see her in a state of near-madness and physical sickness. She is wasting away, weak, her body twisted; and we soon learn (after much prying on the part of the Nurse and Chorus) that her sickness is lovesickness—though it is not eros that has made her ill, but her resistance of eros. Phaedra tells us:

|

Once I saw how my trouble was developing, I knew there was no medicine with which I could combat it; there was no changing my mind. Now I will tell you the way I reasoned it out. When love had wounded me I looked about how I might best put up with it. I began with the resolve to keep quiet and hide my disease…next, I intended to overcome my folly by my self-control, and so endure it. And thirdly, when I could not master Cypris by these means I thought it the best plan…to die. As I would not wish my good deeds to pass unnoticed, so I did not want a crowd of witnesses to my sin…There you have my reason for killing myself: the desire to spare my husband and children that shame. |

|

|

Phaedra becomes an interesting sort of parallel character to Hippolytus. She has also committed herself to a kind of chastity—though she feels eros in a way that Hippolytus might not, she refuses to act upon it for the sake of her reputation and good name. Rather than bring shame to herself and her family, she tries to kill herself by refusing to eat. This self-inflicted punishment is particularly interesting in that it implies a desire for control.

If death was Phaedra’s only goal she could have achieved it differently, with a faster method (as we will see her do later in the play), rather than draw out her suffering; but her refusal to eat demonstrates a determination to have absolute control over her body and her natural instincts, which include her amorous desires. Phaedra is, in her own way, obsessed with the law and its clear-cut demands. Adultery is not only unlawful, but also incredibly shameful, and so her eros must be rejected in favor of nomos, even if it means Phaedra’s death. In fact, Phaedra is so supportive of the law that her support turns into a hatred of women similar to that of her stepson. She says:

|

I realized full well that I was that object of universal detestation, a Woman. A foul curse on the woman who first committed adultery with strange men!…Those women who talk chastity, but secretly have their disreputable affairs, I hate. Sea-Goddess Cypris! How in the world can they look their husbands in the face, without quaking for fear lest the darkness, the partner in their crimes, some day take voice; or the walls of their chamber? |

|

|

A World Without Eros

Phaedra, like Hippolytus, wants to live in a world in which eros does not interfere with the carrying out of nomos—and nomos, for her, is very linked with the idea of reputation and societal custom. Shame is Phaedra’s worst enemy—she cannot bear the thought of what people will say. Interestingly enough, one has to wonder whether Phaedra’s acute sense of shame and hatred of adultery is a result of her own family history.

Hippolytus rejecting Phaedra, by Jozef Geinaert

Her mother, Queen Pasiphae, had an adulterous affair with a bull and gave birth to the legendary Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull monster. Perhaps the labyrinth that was this monster’s home was not built solely for the purpose of sacrificing Athenian youth, but also as a way for King Minos to inter the family shame.

It is partly for this reason, really—the obsession with nomos that both Phaedra and Hippolytus share—that Aphrodite’s plan works so brilliantly (or perhaps it would be more appropriate to say tragically). Phaedra’s fear of shame is what leads her to fabricate the lie that Hippolytus raped her, in order to hide the true reasons for her suicide and save face, and Hippolytus’ refusal to break an oath sworn before Zeus, even when his life is in danger, both ultimately lead to the success of the divine plan.

Whatever Happened to Theseus?

This brings us to a new question: what is Theseus’ role in this divine plan? He is central to the decisions of the other characters, and yet he is absent for the better part of the play. Theseus is a particularly interesting character in that for all intents and purposes, he seems to be a great bastion of nomos.

Despite being king of Athens, he does not consider himself exempt from the law. In fact, the only reason he and Phaedra are in Troezen (the setting of Hippolytus and Hippolytus’ home) is Theseus’ obsession with following the law, even when technically unnecessary. Theseus, in an effort to defend his throne, killed several of the Pallantides (Pallas’ sons)—this would have been considered a perfectly justified killing (especially as the Pallantides were attempting to attack Theseus first), but Theseus imposed upon himself a needless year-long exile in Troezen, simply for the sake of ritual tradition (and despite the danger involved in leaving his throne unattended—he did not kill all the Pallantides, after all).

By this example alone, Theseus seems as obsessed with the law as are his wife and stepson; and yet, there is a side to him that is not quite that committed. After all, Hippolytus himself is proof that Theseus has committed adultery and has had children out of wedlock (we must remember, too, that Hippolyta is not the only woman Theseus kidnapped—he has committed this crime more than once). Moreover, there is an implication in the play that Theseus is not adhering to the laws of legitimacy and succession. Phaedra’s nurse, while attempting to discover the source of Phaedra’s illness, says:

|

if you die you will betray your children and deprive them of their father’s house, as sure as the horse-loving Amazon queen bore a master for your own children, a bastard, but with no bastard heart. |

|

|

According to Benardete, the Nurse’s argument does not make sense unless we assume that Theseus is considering Hippolytus as an heir. “Why should the illegitimate Hippolytus be favored over Phaedra’s legitimate children?” he says, “Her death cannot be the cause; rather, Theseus must already have decided to make Hippolytus his heir, and only if Phaedra stays alive could he possibly be dissuaded”.

If this is truly the case, it means that Theseus is openly defying the laws of marriage and legitimacy, and it would not be bold to assume that Aphrodite’s plan is meant to punish Theseus as much as it is meant to punish his son. There is actually a small hint of this idea in Aphrodite’s opening speech. “Yes, she must die;” Aphrodite says of Phaedra, “I shall not let the thought of her suffering stop me from punishing my enemies to my heart’s content” (76 – emphasis mine). In many ways, Theseus has insulted the ideals of lawful marriage and family just as much as Hippolytus—Aphrodite could easily consider him an enemy.

One has to wonder whether Theseus’ disregard for these laws is actually due to a deep-seated mistrust of his own legitimacy. According to the legend of his birth, Theseus’ mother, Aethra, slept with both the king of Athens, Aegeus, and Poseidon in one night. Theseus is thus considered to have a dual-paternity (this is part of what gives him his heroic strength and bravery). However, if viewed from a different standpoint, Aethra’s night with two men would not lead to dual-insemination, but instead to an uncertainty about the true paternity of the child. There is no way of knowing for certain, then, whether Theseus has a right to the Athenian throne (This is also throws into question Theseus’s killing of the Pallantides. If he is not truly the heir of Aegeus, the deaths would not have been considered justified. Perhaps this explains his seemingly overzealous need to purify). This is further complicated by the fact that Aegeus and Aethra were not in a lawful marriage at the time of Theseus’ conception—so, even if Aegeus is truly Theseus’ father, the law should have prevented Theseus from ascending the throne. How much of himself does Theseus see in his son?

It is clear, then, that the Hippolytus is about much more than a woman who falls in love with her stepson and a father who makes a horrible mistake. That tragic surface-story hides a complex struggle between eros and nomos—two fundamentals that are often mistakenly believed to exist separately from each other. In fact, eros and nomos are inextricably linked—we see this in the similarities between the goddesses (a fact that Hippolytus tragically fails to recognize) and in the failure of each character’s attempt to reject the one in favor of the other.

The presumptuous rejection of eros leads to nothing but pain, and it seems like no coincidence that the play opens with an image of Phaedra’s wasted, writhing body and closes with an image of Hippolytus’s body reduced to bloody tatters. Their rejection of nature—their desperation to live in a state of perfect and impossible lawfulness—destroyed them both; and Theseus, who had no small role to play in the matter, is left to pick up the pieces.