By Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Odysseus and the Sirens, an 1891 painting by John William Waterhouse

“For with their high clear song, the Sirens bewitch him, as they sit there in a meadow piled high with the moldering skeletons of men, whose withered skin still hangs upon their bones.” Odyssey. 12: 39-54

The elusive Sirens of the Aegean have been cornerstone characters in Greek mythology since the 7th century BCE. The two Sirens (sometimes three), Scylla and Charybidis reside in the Strait of Messina between Italy and Sicily- a common passage in the ancient World for ships conducting trade, expeditions, and contacts with the Central Mediterranean powers. Having prominent scenes in the Odyssey and the Argonautika, and being heavily featured in vase paintings in the Aegean, Italy, and Sicily, the Sirens are well-known to us today.

Beautiful singing, captivating, fatal women of the sea permeate even children’s material, like The Little Mermaid…but, these half bird, half woman creatures are more complex than we may think at first glance.

The Origin of Sirens

Attic funerary statue of a Siren, playing on a tortoiseshell lyre, c. 370 BC

Like most mythical creatures, the origin of the Sirens is unknown. Their parentage may come out of Gaia, Phorcys, Achelous, Sterope, and/or one of the Muses. Their concept in mythical terms is thought to be of eastern origin, brought over to Greece during the Orientalizing period when artistic motifs, themes, and ideas were adopted from Syria and Assyria.

Some scholars have referred to the Sirens as ‘Soul-Birds” while others have considered them “other world enchantresses.” These soul-birds, an idea put forth by Georg Weicker, were essentially representations of the souls of the dead, who resided in the underworld. The Sirens then, acted as tests to seafarers traveling the dangerous straits, failure of which resulted in death.

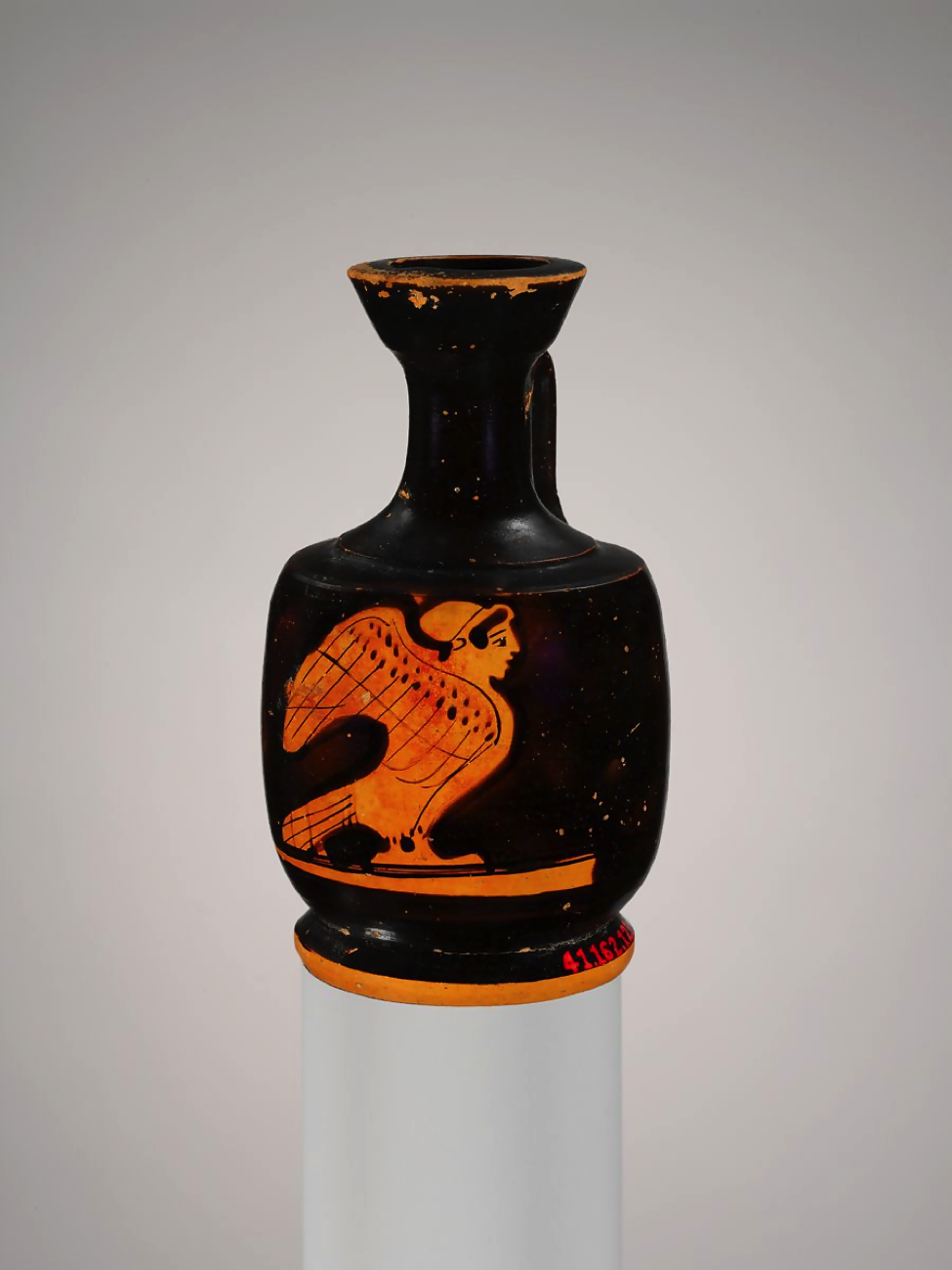

Miniature terracotta squat lekythos (oil flask) with siren. Culture: Greek, Attic

The Form of Sirens

The form of the Sirens, in both literature and art, is relatively consistent: the body of a bird, the head of a woman and sometimes with human arms. Circe, in Odysseus 12 describes the Sirens:

“She has a voice as loud as a new-born puppy’s, but she herself is an evil monster. No one would enjoy the sight of her, not even if a god should encounter her. She has twelve feet, all hanging in the air, and six necks, very long ones, and on each is a terrifying head, with three rows of teeth in it crowded close together, filled with dark teeth.”

The picture painted here is not one of a beautiful, seducing figure, but one of a grotesque, terrifying monster that does everything she can to lure men to their death.

Miniature illustration of a siren enticing sailors who try to resist her, from an English Bestiary, c. 1235

But is the very form and description of the Sirens a personification of the natural environment of the Straits? Some think so. The voice of a “new born puppy’s” could represent a seal, the many feet hanging off her body possibly an octopus, and the triple set of teeth can be a small shark. Charybdis is described as sucking in ships and spitting them out in pieces; a phenomenon that can easily be likened to whirlpools.

So, like many mythical creatures and legends, are the Sirens a way for people to cope with the unexplainable difficulty plaguing this passage of sea? It certainly seems that way.

Odysseus and the Sirens

Odysseus and the Sirens, Roman mosaic, second century AD (Bardo National Museum)

Perhaps one of the most poignant representations we have of the Sirens comes from book 12 of the Odyssey. The episode is split up between Circe’s foretelling of the event and Odysseus and his men’s actual experience. On their wanderings home, Odysseus and his men arrive at the Sirens’ island which is accompanied by an eerie calm. The crew plugs their ears with wax, Odysseus is tied to the mast, and they row closer to the island. When Odysseus asks to be set free, so he can succumb to the Sirens’ song, the crew ties him tighter so he can resist. They are able to pass, enduring the Sirens’ call and continue their journey.

It’s a short episode, but one that offers a great revelation into the Sirens. It shows who the Sirens were, what they did to entice sailors, and how ‘heroes’ can pass such a test.

Representations of Sirens

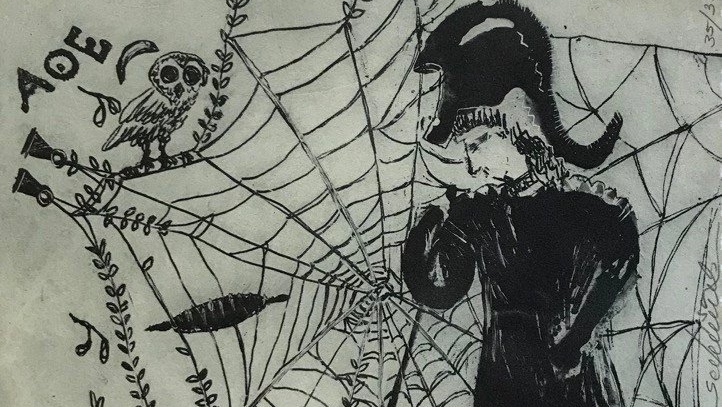

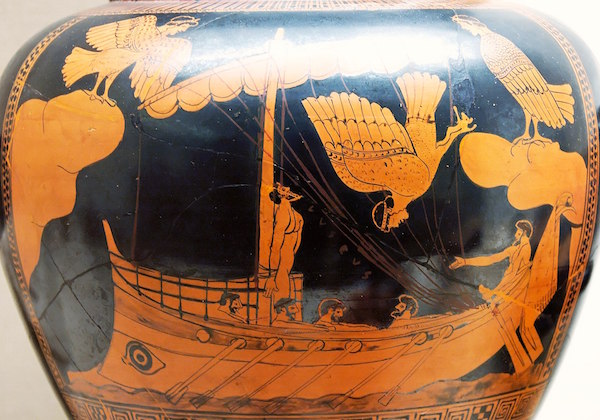

Odysseus and the Sirens, eponymous vase of the Siren Painter, c. 475 BC

The Sirens were a common motif in vase painting, especially in Sicily and Italy. The combination of mythical creatures and Homeric themes was popular and desirable.

One vase, however, stands out amongst the rest. The so-called “Siren Vase” depicts the very scene in the Odyssey where Odysseus is tied to the mast, the men’s ears are filled with wax, and the Sirens are trying to entice them to their demise. It dates to 480-470 BCE and was produced in Attica.

Sirens: From Sea to Prostitute

The representation over time of the Sirens changed dramatically. Indeed, in the very beginning Sirens were shown to be male or female, but the male Siren disappeared from art around fifth century BC. Eventually the grotesque image of the Siren evolved to where their form was as beautiful of their song.

Ulysses and the Sirens, by Herbert James Draper, c. 1909

With this dramatic change, so too did their symbolism transform. No longer a metaphor for the sea, the Siren became the tempting seductress.

The Early Christian euhemerist interpretation found in Isidore’s Etymologiae (circa 600) described them as such:

They [the Greeks] imagine that “there were three Sirens, part virgins, part birds,” with wings and claws. “One of them sang, another played the flute, the third the lyre. They drew sailors, decoyed by song, to shipwreck. According to the truth, however, they were prostitutes who led travelers down to poverty and were said to impose shipwreck on them.” They had wings and claws because Love flies and wounds. They are said to have stayed in the waves because a wave created Venus.

It is this final image of the Siren that has preserved so thoroughly in art and cultural references. Just what our modern reinterpretation of this once terrifying mythological monster says about us, and the modern world we navigate, is for the reader to decide.

By Brittany Garcia, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

While most people know about the ancient Greek monsters like: centaurs, harpies, cyclopes, mermaids, sirens, the chimera, hydra, giants, and et cetera; the goal of this survival guide is to expose the truth behind the uncommon Roman monsters that hide under our very noses!

The following monsters are very dangerous and should NOT be approached under any circumstance. Most of these creatures and monsters eat people, so if you see one please contact your local animal control or ancient history enthusiast.

1. Yale or Eale

Illustration of the Yale or Eale

Meaning of Name: “To move back” – perhaps in reference to its horns.

First Spotting: Ethiopia

Form: Antelope or goat-like creature that is the size of a hippopotamus, with an elephant’s tail, usually black or tawny in color, with the jaws of a boar and movable horns.

Food: People and large animals

How it attacks: Presumably, it must ram its prey with its moveable horns and tusks.

Latest Spotting: A popular emblem in medieval times for royal banners, the yale or eale has found its way to Yale University’s banners and perhaps into the basements of the campus itself.

Weaknesses: Other Eales or Yales, tall mountains, and loud university rallies.

Sources: Pliny the Elder’s Natural History.

2. Manticore

Manticore

Meaning of Name: Man-Eater

First Spotting: Persia

Form: Body of a red lion, a human head, with a trumpet-like voice. Sometimes it is seen with horns or wings.

Food: People and large animals

How it attacks: Its tail has been found in the form of a dragon or scorpion which shoots poisonous spines that paralyze and kill its victims.

Latest Spotting: Commonly, the manticore has been spotted in archaic themed video games such as God of War and Age of Mythology. Recently, one manticore was seen debuting in his first film: Percy Jackson and Sea of Monsters. He sadly did not survive to make a sequel.

Weaknesses: A ranged weapon…maybe or, it is probably just best to stay away.

Sources: Ctesias, Indica, Pausanias, Guide to Greece, Aelian, On Animals, Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana, Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Eusebius, Against Hierocles, Photius, Myriobiblon.

3. Basilisk or Regulus

illustration of Basalisk

Meaning of Name: “Little King”

First Spotting: Cyrene, Libya

Form: A small snake “not longer than twelve fingers” with a crown shaped crest on its head. At times, the basilisk is seen with the head of a cockatrice due to its odd birthing ritual involving a toad and cockatrice.

Food: Anything!

How it attacks: By bite or gaze; its bite or gaze is extremely lethal.

Latest Spotting: A large basilisk was spotted in the early Harry Potter film franchise living in Hogwarts’ pipes. Rowling also mentions its presence in her own monster guide book: read it here. Its eggs are a unique and rare item that players attempt to find in the latest video game: Final Fantasy XIV.

Weaknesses: The scent of a weasel for some reason scares and may even be lethal to Basilisks, so when going out this Hallow’s Eve make sure to have your special weasel “perfume” at the ready! Also, a mirror to reflect its lethal gaze may work as well.

Sources: Pliny the Elder’s Natural History

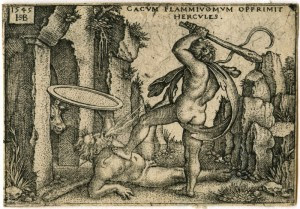

4. Cacus

Illustration of Cacus

Meaning of Name: “The Evil One”

Origins: Rome; Aventine Hill

Form: A giant who breathes fire and smoke. He is the son of Vulcan.

Food: Human flesh, but not their heads. He nails the heads of his victims decoratively outside his cave.

How it attacks: He attacks and kills its enemies and prey by breathing fire and smoke onto them.

Latest Spotting: While Cacus has not been seen since Hercules apparently strangled him to death; The Percy Jackson series makes mention of him; suggesting that he did not die or has a brother.

Weaknesses: Divine strength or a big club. Let’s take a tip from Hercules and use the skills of a demi-god to defeat this monster and any of his siblings.

Sources: Virgil, Aeneid, Ovid, Fasti, Propertius, Elegies.

5. Amphisbaena

Illustration of Amphisbaena

Meaning of Name: “Mother of Ants”

First Spotting: Libyan Desert sprouting from the blood of Medusa’s head, and later by Cato’s army.

Form: A two headed serpent, whose tail has the second head; however this “serpent” is about the size of a long worm. The addition of wings and chicken feet was reported by later sightings.

Food: Anything living or dead

How it attacks: It has a poisonous bite.

Latest Spotting: They appear to have been a popular inspiration within Insular art during the Middle Ages; however they are said now to be “summoned” by a Dungeon Master when playing the game: Dungeons and Dragons.

Weaknesses: Really thick shoes and an aggressive stomp.

Sources: Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, Aelian, On Animals, Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History.

Safety and Caution Procedures

Now, while most of these monsters will leave you alone if you leave them alone; if you happen to run into one of these creatures you must :

I. Run as fast you can and avoid eye contact

II. Summon your inner hero strength and fighting skills

III. Pray to the Roman Gods

IV. Rent a Pegasus and fly away.

DISCLAIMER: The Unofficial Ancient Roman Monster Survival Guide is neither responsible for any harm or deaths that occur as a result of “monster hunters or enthusiasts” attempting to capture or tame these creatures.

By Julia Huse, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom Limited

Of the monsters and mythological creatures Odysseus encounters during his long voyage from Troy to Ithaca, among the fiercest are female. Three of these are Circe, the Sirens and Calypso, who all prove to be difficult and terrifying obstacles to Odysseus’ journey home.

The Witch Circe

The witch Circe poisons Odysseus’ men, Alessandro Allori, 1580

After escaping the island of the cannibalistic Laestrygonians, Odysseus and his crew stumbleupon Aeaea and the home of Circe, who is referred to as both a witch and a nymph. She has a vast knowledge of potions and herbs, which Odysseus and his crew experience first hand. Odysseus and half his crew stay behind with the ships while the others go in search of Aeaea to see what people live there. The search party comes across the home of Circe, which is described as a large house in a clearing in the middle of a thick forest. All around the house are lions and wolves, which at first frighten the crew… until they notice how docile the beasts are. It is later found out that these are the previously drugged victims of Circe and her potions. In her house Circe welcomes Odysseus’ crew as guests, feeding them a meal of cheese and honey which she has drugged, turning the crew into pigs.

All but one crewmember is changed into a pig and he manages to escape to warn Odysseus and the other half of the crew what has happened. Odysseus ventures to Circe’s house to save his men, but is stopped along the way by the god Hermes, who was sent by Athena. Hermes tells Odysseus of an herb called moly that will protect him from the potions of Circe. Immune to her potions, Odysseus acts as if he is going to attack her. Afterwards, she tries to coax Odysseus into bed with her, which he avoids, due to Hermes’ advice. Having done all this, Odysseus convinces Circe to turn his crew back into humans and free them.

The Sirens

Ulysses and the Sirens, Herbert James Draper

Odysseus also encounters the famous sirens during his wanderings. Typically in Greek depictions, the sirens they are half-woman half-bird creatures that perch on the rocks by the sea and sing beautiful songs that lure men who, refusing to leave, die of starvation.

In the Odyssey, Circe warns Odysseus about the sirens and tells him to plug his and his crew’s ears with beeswax in order to block their sweet songs from entering their ears. Being curious about the songs the Sirens sing, Odysseus only plugs his crew’s ears with beeswax and then has his men tie him to the mast of the ship, instructing them not to untie him… no matter how much he begs for it. Odysseus hears the song and begs and pleads that his crew release him, but his faithful crew only tighten the ropes more, binding him to the mast.

It is then revealed that the reason the songs allure and entice men is because they sing of past and future truths. They sing to Odysseus about his past endeavors, such as the glory and suffering he endured on the battlefields of Troy, and his future actions and what he will achieve… and they falsely promise that their hearers will live to tell these truths to others. Odysseus, of course, achieves this and this is how we are able to get this account from him.

The Nymph Calypso

Calypso by Henri Lehmann (1869)

At the end of his wanderings Odysseus washes up alone on the island Ogygia, the omphalos, meaning navel or center, of the sea, and also the home of the nymph Calypso. Homer describes Calypso as the daughter of the Titan Atlas, who holds up the pillars of the sky and the sea. In Homer’s epic, Calypso keeps Odysseus on her island for seven years, accounting for a large part of his journey home. Calypso desires to make Odysseus her immortal husband and enchants him with her singing as she weaves on her loom. Odysseus performs all the duties of a husband for Calypso, including sleeping with her.

Even under Calypso’s spell Odysseus desires a different life. The promise of immortality does not sway him from missing his wife Penelope. Odysseus, a man, does not desire the life of a god; he much prefers the life of a mortal, even with all its hardships that are so clearly lacking on Calypso’s island. Noticing that Odysseus wants to leave the island, Athena asks Zeus to order Odysseus’ release. Zeus sends Hermes to tell Calypso to release Odysseus because it is not his fate that he should remain on the island forever anyways. Calypso eventually, and stubbornly, agrees to free Odysseus and sends him on his way with wine, bread and materials for a raft.

Beguiling Women of Ancient Greece

These women, although not necessarily terrifying in their looks, are certainly terrifying in their abilities to enchant mortal men. With much help Odysseus is able to resist or break free from these enchantments. Even the seemingly least threatening woman of the three, Calypso, manages to keep Odysseus detained for seven years, proving to be one of the greatest obstacles to his journey.

Clearly the women are seen as enchanters and deceivers of men, distracting them from their intended course or purpose… and this reflects a feeling found in Ancient Greece that women were deceitful creatures who could not control their sexual desires and sought to entrap men. This becomes especially clear when compared to male monsters, such as the Cyclops Polyphemus, who does not have the enchanting and deceiving nature of these woman. Odysseus immediately sees through his deceit and is able to win against Polyphemus with his own trickery. Whereas Odysseus can detect this deception on his own, when it comes to women monsters and goddesses, he needs the help of the gods and others to warn him and help him break free.

By Nicole Saldarriaga

What does it take to feel sympathy for a monster? In the case of Medusa, it may not be much. Though she is considered one of the most horrifying creatures of Ancient Greek mythology (coming in at second place on Classical Wisdom Weekly’s “Top Ten Most Terrifying Monsters of Greek Mythology”) her origin story is much more complex than most people realize—in fact, most people have never heard Medusa’s origin story at all.

This may be simply because the sources available to us today differ so widely in the telling of Medusa’s story—in fact, the tale functions as a brilliant example of the way in which myths evolve over time to suit changing societal needs. Though the myth started out simple, it quickly grew and, in some ways, changed drastically—leading to a great deal of confusion when modern readers and researchers attempt to put the pieces together into an accurate representation of ancient thought.

There is, of course, some information about Medusa that never changes no matter what source you choose to look at. These are details that are incredibly well known, and seem to be passed along through a process of natural cultural osmosis. Medusa is a kind of creature called a Gorgon, she has hundreds of wild, venomous snakes for hair, and she can turn any person to stone with a single look. This concept has fascinated people for centuries, and various kinds of paintings, sculptures, cartoons, video games, and even brand labels have explored Medusa as a subject and character.

But these are the details almost everyone knows. Almost everyone knows who Medusa is, or at least what she can do. What is more interesting is how Medusa became the monster she is considered to be, and this is where the myth begins to warp and change as sources begin to disagree.

The concept of a monster such as a gorgon is an incredibly old one in Greek mythological history. We know from the creature’s appearance in the very ancient myths of Perseus and Zeus that the notion of a dreadful, snake-haired, deadly woman was born quite early. As far as the gorgon’s presence in classical literature goes, the earliest known mention of such a creature appears in Homer; and while no one can be sure of Homer’s timeline (or even his exact identity), some scholars believe that he penned his work around 1194-1184 BCE—indicating that the Ancient Greeks were talking about gorgons at a very early stage of their history.

Though Homer’s exact timeline is unknown, his mention of the gorgon places the myth among some of the oldest recorded myths of Greek history.

In the Odyssey, the gorgon is a briefly mentioned inhabitant of the underworld—one whom Persephone could apparently “sic” on anyone who angered her. It isn’t until several years later that another author gives the gorgon more of a backstory. Hesiod, in his Theogony (700 BCE), describes the gorgons as three sister-monsters born of Phorcys and Ceto, two primordial ocean deities. He calls them Stheno (“the mighty”), Euryale (“the wide wandering” or “the far springer”), and finally, Medusa (“the cunning one” or “the queen”). He also describes a key difference between Medusa and her two sisters, one that becomes extremely important later: Medusa, unlike the other two gorgons (and for reasons not explained), is fully mortal.

In these earlier myths then, it’s assumed that Medusa was born a monster—complete with snakes and stony vision. However, there is evidence that the myth changed drastically over time.

Around 8 AD, Ovid—a Roman poet celebrated for his faithful retelling of popular Greek myths—produced his famous Metamorphoses, an expansive book of myths which includes the myth of Perseus and his slaying of Medusa. In this section of the book, Ovid gives a completely different origin story for the terrifying creature.

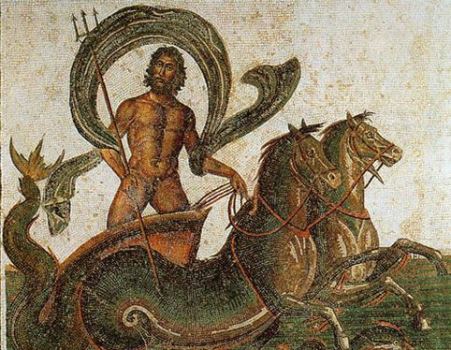

According to Ovid, Medusa was born human and grew into an excruciatingly beautiful woman. Every man who saw her face and her gorgeous, silken hair immediately asked for her hand in marriage—all but one. The sea god, Poseidon, fell for her amazing looks but instead of asking for her hand, took her virginity—raping her inside the sacred sanctuary of Athena.

Athena, as the virgin goddess, was incredibly enraged by this defilement of her temple and chose to punish Medusa for her part in the whole affair—she cursed Medusa’s beauty. According to this version of the myth, it’s at this point that Medusa’s beautiful hair becomes a tangled mass of snakes, and she is cursed with her deadly power—the ability to turn whoever looks upon her to stone.

It’s important to stress here that Medusa has no control over this ability—should anyone at all look upon her face, they’ll be instantly transformed. In essence, Athena dooms Medusa to a life of solitude, a life in which Medusa will never have the comfort of looking at another human face without destroying it—all for the crime of being raped. After years of this torture, Perseus’ sword must have come as a welcome deliverance.

Of course, this is just one version—but it has had a profound impact on the evolution of the myth and especially its propagation in modern times. These days, the most well-known (though that isn’t saying much) origin story for Medusa is closest to Ovid’s version, with only a few added details—that Medusa was a celibate priestess in the temple of Athena when she was raped, and that in addition to cursing her with a head of snakes, Athena transformed Medusa into a hideous old hag with greenish skin and fangs. But this isn’t the only version that is being passed along today.

As part of my research for this article, I read through several fan-based mythology forums, online blogs, and similar websites on which people had posted their own retellings of Medusa’s origin. The changes to the story that have taken place over time are fascinating, and are really testaments to the transformative power of imagination and word-of-mouth.

Many amateur mythology enthusiasts claim, for example, that Medusa was never raped at all. Instead, they say, she was obsessed with her own beauty and tired everyone around her by bragging about it incessantly. One day, she visited the temple of Athena with friends and spent the entire time claiming that she was more beautiful than the goddess herself, for which the goddess cursed her with an appearance so horrifying that it could turn people to stone.

This is a very interesting mixture of Ovid’s version (in which Medusa is punished for defiling Athena’s temple, though in this case the defilement is her insult to the goddess within its sacred walls) and what is possibly a misinterpretation of a line in Apollodorus’ Bibliotheca (another collection of myths dating to somewhere between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD). According to Apollodorus:

“But it is alleged by some that Medusa was beheaded for Athena’s sake; and they say that the Gorgon was fain to match herself with the goddess even in beauty” (2.4.3.).

This tells us nothing about whether Medusa was once a beautiful human woman, and clearly does not claim that Athena transformed her into a Gorgon for her arrogance, but is instead referencing her much later beheading. Still, it’s likely that this idea was passed on, and eventually led to the modern interpretations that claim Medusa’s gorgon status was punishment for her vanity.

Whether Poseidon raped Medusa, or simply took on the role of a gentle lover, it’s clear that Medusa was doomed from the moment they stepped into Athena’s temple.

Still other modern story-tellers claim that Medusa’s life was a tragic love story—that Poseidon loved her, intended to marry her (or in some versions, did marry her) and the couple made the unfortunate (and inexplicable) decision of consummating that love in Athena’s temple. In that case, Athena’s curse (while obviously worse for Medusa) is a way of punishing them both—ensuring that they would never be able to look upon each other again.

It’s more difficult to trace the potential origins of this interpretation, but it’s possible that Hesiod’s description of Medusa’s relationship to Poseidon—in which the god beds her in a romantic field of wildflowers (lines 278-79 of Theogeny) may have had something to do with it—though again, it’s only two lines of text and does not specify whether Medusa was already a “monster” when Poseidon became interested (we all know the gods weren’t exactly picky).

What’s clear from all of this is that Medusa not only lives within the realm of myth, but also within a liminal space. As long as her story is so variable, she is both monstrous and beautiful, both born to kill and cursed to a life of solitude, both arrogant and humble, both loved and horribly raped. Her story is open for us to take from it what we choose—horror and derision for a simple mythological villain, or pity and sympathy for a girl whose life was taken out of her own hands and changed very much for the worse.

I know what I’m choosing.

By Nicole Saldarriaga

If you think the Sirens are the only mythological beings capable of making music deadly, think again. Mythology gives us another, much older trio of ladies whose song was meant to torture and kill their victims. They go by many names, but at least one is eminently recognizable: they are often called the Furies.

According to most mythological accounts, the three Furies—named Alecto (the unceasing), Megaera (the jealous), and Tisiphone (the avenger)—were literally born of blood. They sprang into being after the Titan, Kronos, castrated his father, Uranus. The blood from Uranus’ wound fell to the earth (Gaia) and produced the Giants, the Furies (or Erinyes), and the Meliae (a kind of nymph).

This bloody backstory is particularly important to the Furies for two reasons.

First, it establishes their age and lineage—they are older even than the Olympians, and are the direct result of a co-mingling of two primeval forces (Uranus, the heavens, and Gaia, the earth). Second, they are also the result of a crime committed by a son against his father. Fittingly, then, for many years the Furies were considered avengers of violations to the natural order—if a man killed his parents, for example, he could expect to answer to the Furies.

By all accounts, the Furies were visually terrifying. They had the bodies and faces of twisted old women, with writhing snakes for hair, runny eyes, and tattered black clothing. They punished their victims with a wild paralytic song that aroused intense feelings of guilt and remorse—essentially, the Furies drove criminals mad by exposing them to their own guilt and fear.

The Furies were, for all intents and purposes, monsters. They may have been monsters seeking justice, but they were terrifying monsters nonetheless.

The Furies

The FuriesAnd yet, believe it or not, they were worshipped in Athens. They had their own sanctuary and sacred grotto, and were called the “Eumenides,” meaning “the kindly ones.”

Okay—what gives?

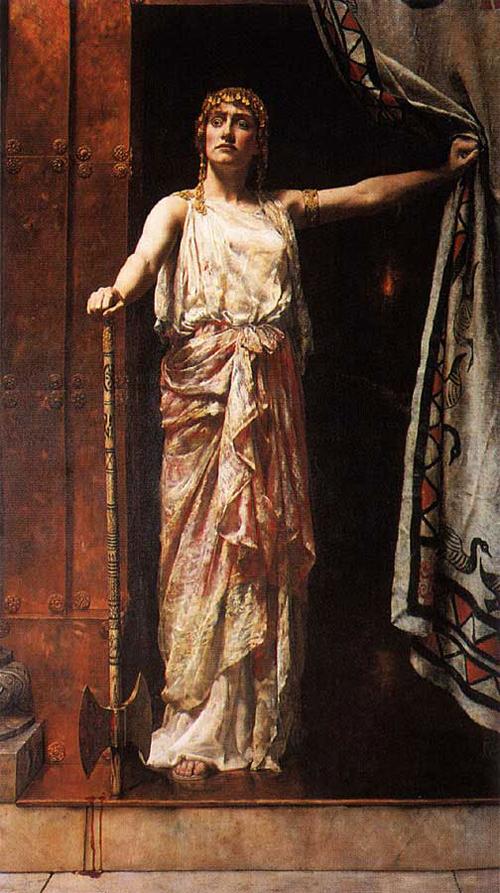

One of the best sources to look to when trying to understand Athens’ worship of the Eumenides is actually a trilogy of plays called The Oresteia, by an Ancient Greek tragedian named Aeschylus (c. 525-456 BCE). In these plays he not only tells the tragic story of Agamemnon, Clytemnestra, and Orestes, but also essentially gives us an origin story for Athens’ famous trial-by-jury system of justice.

It’s in the last play of this trilogy, called The Eumenides, that we can see a distinct shift in the function and identity of the Furies. But before we can understand how they went from being the Erinyes (“the angry ones”) to being the Eumenides (“the kindly ones”), we have to understand why they make an appearance in the trilogy in the first place.

According to legend, Agamemnon, the commander of the Greek army in the Trojan War, was brother to Menelaus, whose wife, Helen, was taken by Paris (a crime against hospitality that started the war to begin with). Before the Greek army can set sail for Troy, Agamemnon and Menelaus are told that they must sacrifice Agamemnon’s daughter, Iphigenia, to appease the goddess Artemis—otherwise they will be unable to sail.

Clytemnestra after the murder, by John Collier

Clytemnestra after the murder, by John CollierTo make a long story very, very short, Agamemnon ritually kills Iphigenia, devastating his wife, Clytemnestra, who, upon Agamemnon’s return from the long war, murders him in his bath. Orestes, their son, who was away from home at the time of his father’s murder, eventually returns home and avenges his father’s death by murdering Clytemnestra and her lover.

This, clearly, is where the Furies come in. Their purpose is to punish violations of the natural order, such as Orestes’ killing of his own mother, and they get to work almost immediately. Circumstances matter very little to them—it doesn’t matter that Clytemnestra killed her husband first, Orestes must still be punished for killing his mother (a much stronger blood tie than husband and wife). By the end of the play in which Clytemnestra’s murder takes place, The Libation Bearers, Orestes is tormented by “ghastly women, like Gorgons,/ with dark raiment and thick-clustered snakes/ for tresses” (1048-49). He runs offstage, screaming about their terrifying appearances.

Apollo (who encouraged Orestes to commit the murder in the first place, but the Furies care little about this detail) tells Orestes to travel to the sanctuary of Athena, where he must embrace her idol and beg for assistance.

Once Athena responds to Orestes’ plea and enters the action, she pulls together Athens’ first jury trial in order to decide once and for all whether Orestes deserves punishment for his actions, or whether he acted in the right.

This is a fascinating section of the play which normally deserves a great deal of attention, but for now we are focusing on the Furies. So, to make a long story short (again), the jury of Athenian men finds Orestes “innocent” in the sense that his actions were justified. The Furies are, of course, extremely unhappy with this answer, and Athena has to do some damage control. She asks the Furies to stay in Athens—and she asks them no fewer than four times (sweetening the deal each time) before the terrifying trio decides to stay.

If the Furies represent such a pernicious form of torment, why is Athena so desperate to have them stay in Athens? On the one hand, she must protect her city from the threat of the Furies, who specifically proclaim that if Orestes is freed, they will spread venom throughout the land: “a canker, blasting leaves and children…speeding over the ground/ shall cast upon the land infections that destroy its people” (785-787).

Although it seems that banishing the Furies before they have a chance to curse the land is the obvious solution, the text actually implies that the Furies’ curse would come about as a result of their permanently leaving the land.

The Erinyes, after all, are in many ways a personification of righteous guilt. If guilt were to leave Athens forever, the city would be destroyed. This is why the Furies mention children in their threat—human beings who feel no guilt or shame could do any number of horrible things to each other without having to fear the internal torment of remorse. In a world like that, it would be difficult to trust anyone, and without absolute trust there can be no love or marriage, without which there would be no children. The Furies, by abandoning Athens, would devastate the family, and without family there can be no Polis. Athena cannot let this happen to her city.

After all, she recognizes that guilt and fear are absolutely essential to the health of civilization. Even if a lack of guilt didn’t pose a serious threat to families, it could still destroy civilized society from the inside out, resulting in absolute anarchy. How could Athena’s newly implemented trial-by-jury legal system be sustained in such a place? “And what city,” say the Furies, “or what man/ that in the light of the heart/ fostered no dread could have the same/ reverence for Justice?” (522-525). Fear and guilt are absolutely essential to the formation of the Athenian legal system, and this is why Athena tells her people that “they shall not cast out altogether from the city what is to be feared/ For who among mortals that fears nothing is just?” (698-699).

But of course, the Furies are not exactly happy with Athena—convincing them to stay is not going to be easy—and in order to make them forget their anger, Athena must “sweeten the pot” pretty heavily; but to do this, interestingly enough, she has to fundamentally change the Furies’ role in society.

Orestes pursued by the Furies, by Louis Lafitte

Orestes pursued by the Furies, by Louis LafitteTo please the Furies, Athena offers them a legally recognized home in Athens, tells them that they will be worshipped after every marriage and childbirth, and that they will also have the power to bring fortune to Athens by controlling the earth, sea, and sky (essentially they will have power over the weather).

These tasks are clearly not what the Furies are used to—and, after all, they are very passionate about bringing evildoers to Justice—why should they accept a new set of duties? Because, in essence, their new roles would still make them fundamentally important to the carrying out of Justice.

As representations of unrelenting guilt, the Furies could never have taken part in Athens’ legal system. The constant presence of unrelenting, overwhelming guilt would paralyze a jury, making it impossible for them to make a decision (for fear of making the wrong one). When Athena gives the Furies power over the weather and over childbirth—things that are fundamentally natural—she instead makes them representations of everything that humans and politics cannot control. By constantly pointing to the forces of nature, the Furies would remind humans that they are limited and imperfect.

This is absolutely crucial to an effective legal system. As a reminder of human limitation and imperfection, the Furies can act as a release from the paralyzing guilt that might make a jury incapable of functioning. A juror who recognizes that he is only human and that he might make a mistake is not overwhelmed by that possibility and is thus able to make a decision. It is a principle that emphasizes the necessity of a decision—of a legal system—over the repercussions of occasionally “getting it wrong.” The Furies are thus transformed into the Eumenides–from fury to “good anger,” from forces of vengeance to forces absolutely necessary to the carrying out of justice.

According to Aeschylus, it’s for this reason that the Furies received their new name and were subsequently worshipped in Athens with an extreme amount of reverence (and more than a little righteous fear). Thanks to Athena’s clever thinking, a trio of horrifying monsters whose only purpose was to torture their victims became a trio of worshipped goddesses who worked together with the Polis to ensure the health of a groundbreaking legal system—a legal system that still lives on in many forms today.

Clearly, the Eumenides have been doing a good job.