The scene was cliche. It was a sunny fall afternoon in New York City and the construction workers were taking their break. Then a stunning woman came down the street…. Not just pretty, but Big Apple gorgeous and dressed… flatteringly.

As she passed the construction workers, I waited for what I thought was the inevitable. But to my surprise there were no catcalls, no whistles or provocative comments. Wow, I remember thinking, perhaps the whole #metoo thing really affected things… maybe this younger generation is much more respectful… maybe culture has changed!

And then I realised it was because the entire row of workers were glued to their phones. They didn’t even notice the beautiful woman.

She also did not notice not being noticed… because she too was staring at her phone. So perhaps culture has changed… just not in the way I had originally thought.

War and Greek Tragedy (Part Three: Euripides)

by Andrew Aulner, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

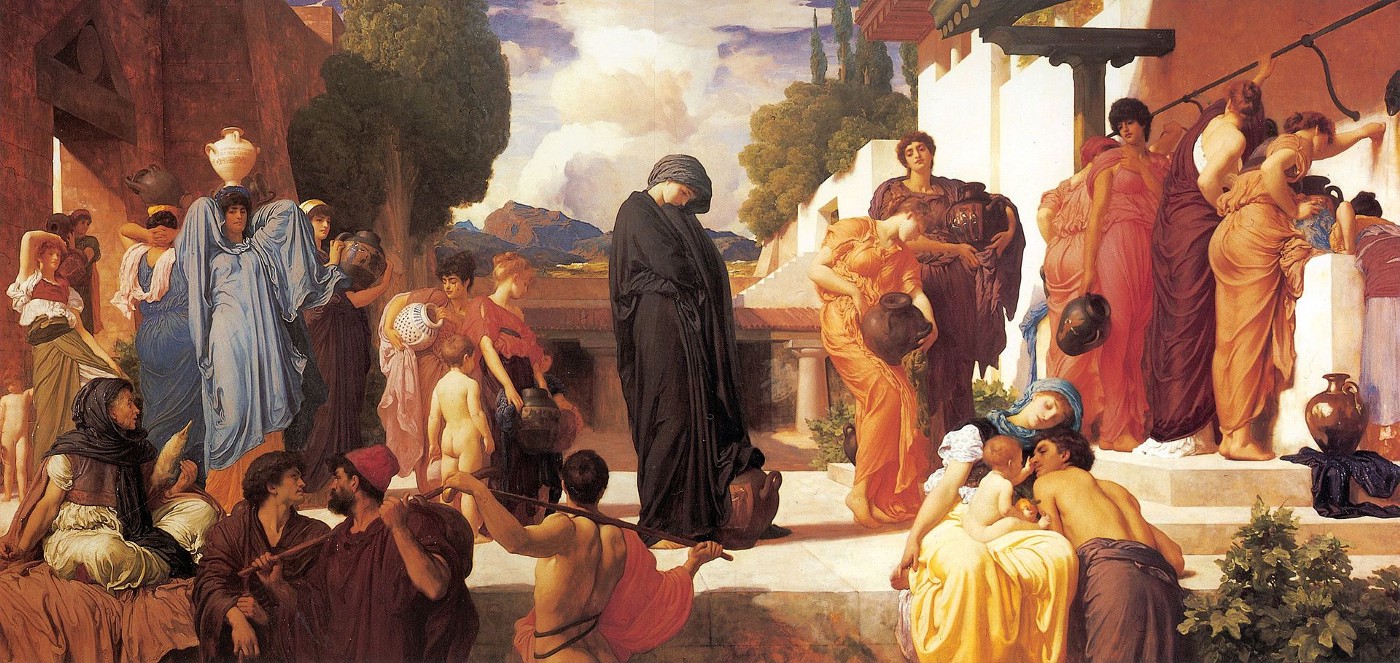

Euripides is unique among the three tragedians in that, unlike Aeschylus and Sophocles, there is no historical record that he ever served in the Greek military. Admittedly, Euripides was able to describe actual battle techniques in Phoenician Women and Children of Heracles, despite the lack of a record of him fighting in any battles. Hanson argues that it is probable that Euripides would have seen military service like his contemporary Sophocles; while there may be no hard evidence that Euripides ever served in combat, he did live through all but the final two years of the Peloponnesian War. In any case, this conflict led him to question his society’s martial values, while also showing him the toll of war upon civilians and returning soldiers.

Euripides lived under the dark specter of constant warfare, and his plays are correspondingly dark in their realism. Apart from being critical of established values, Euripides also subverts those values in reaction to contemporary events. Tritle writes that “…the outbreak of extreme violence [i.e. the Peloponnesian War] in 431 [BC] may have energized Euripides”, who is believed to have written the violent Medea in that same year. As city-states that had formerly been allies against mutual enemies like the Persians turned against each other, and Greek soldiers went off to war against those who had once been their countrymen—all of which suggests a confusing loss of values and morality—it seems fitting that Euripides would write a play in which a character feels justified in murdering her own beloved children in order to hurt her unfaithful husband. Each main party in the conflict, Athens and Sparta, could be viewed as harming their own blood relatives—their fellow Greeks—in order to inflict petty harm against the other. Euripides’ most popular play may never have come to be if not for the war that served as a historical backdrop to it.

This was not the only instance of military events influencing the playwright. The defeat of Athens at the Battle of Delium, as Hanson says, “helped shape Euripides’ developing disgust over the war—and his growing propensity to use his drama to critique contemporary culture even in Athens’s darkest hours”. By the time of the writing of Orestes, Euripides, who had witnessed over two decades of Greeks killing Greeks, goes so far as to condemn war as “‘a friend to lies’”. Even as he questioned Athenian values, Euripides used his stagecraft to declare his own firmly held anti-war beliefs while the world around him continued to crumble.

Aristotle: Happiness is an Activity

Written by Van Bryan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

“For contemplation is both the highest form of activity (since the intellect is the highest thing in us, and the objects that it apprehends are the highest things that can be known), and also it is the most continuous because we are more capable of continuous contemplation than we are of any practical activity.” ~ Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

Our five-week-long inquiry into ancient moral philosophy naturally culminates with Aristotle and his philosophical text known as the Nicomachean Ethics. As we will see, Aristotle asserts ideas that are reminiscent of the Stoics, putting emphasis on attainment of virtue within our lives. However, unlike the Stoics, Aristotle does not rely on a divine cosmology to make his case. Instead, he leans heavily on formalized logic (something he is credited with discovering) and what might be considered a rudimentary form of the scientific method.

At the opening of Book X of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle asks us “…what kind of thing is pleasure?” A notion that we might take for granted, it is very essential to Aristotle’s moral philosophy that we adequately answer this question.

War and Greek Tragedy (Part Two: Sophocles)

by Andrew Aulner, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

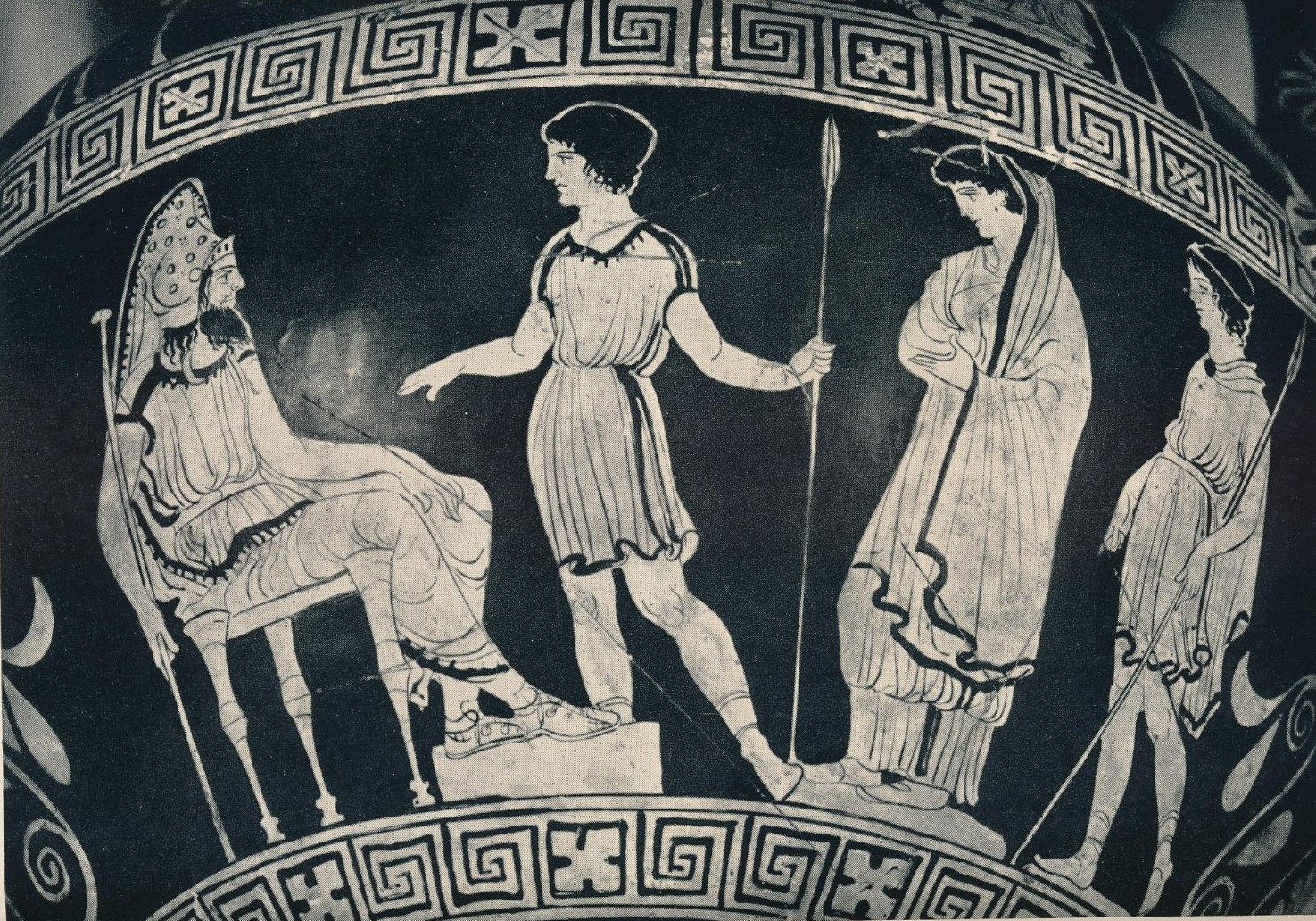

The next of the three great tragedians to be born was Sophocles, who, like Aeschylus before him, served in the Greek military. Sophocles was a general during the war against the island of Samos and later lived through the Peloponnesian War. Both of these events exposed Sophocles to the realities of human suffering, as well as to both the successes and the shortcomings of even the greatest of leaders.

Sophocles served as a general alongside Pericles in 441/0 BC during the Samian revolt, likely serving aboard a small squadron of ships sent to collect reinforcements off of the islands of Chios and Lesbos during naval operations against Samos. According to Woodbury, despite the fact that “Sophocles had no especial political or military claims beyond those of any other member of his class”, the playwright nevertheless “was certainly prominent in the earlier campaign” against Samos. Unlike Aeschylus, Sophocles was more valued as a playwright than as a soldier, though he was still respected for his public service.

There is no question that Sophocles was influenced by his roles as both a participant in and a viewer of the effects of war. Martial violence and leadership are both expressed in the playwright’s examinations of survival and human nature in the face of death and suffering. As Tritle explains, “From Sophocles we hear the bitter and plaintive cries of Philoctetes, the wounded survivor of violence, while from Oedipus come cries of another kind as well as lessons on leadership and knowledge”. Sophocles’ protagonists are written with a keen awareness of deep suffering and pain.

Not Just Another Column

What’s in a column? To the Ancient Greeks, the standing pillar was more than just a way to hold up the roof. Every section, from capital to base, was integral to the entire structure. It was a piece of art that followed very detailed specifications, an architectural order. In fact, you only need a fragment of molding to recreate a whole building.

The ancients weren’t just constructing a safe place in the rain, they were attempting to achieve perfection in architecture.

This meant nothing was left up to chance. It was never, Kyriakos – the average workman and heavy, choosing to put the pediment a “little the right”. The buildings were carefully designed using principles in harmony and symmetry and all overseen by a respected architect. The man in charge presided over every detail, from materials selected to choosing expert sculptors.

The order of the universe, believed so fervently by the Ancient Greeks, was reflected in the buildings themselves.

War and Greek Tragedy (Part One: Aeschylus)

by Andrew Aulner, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

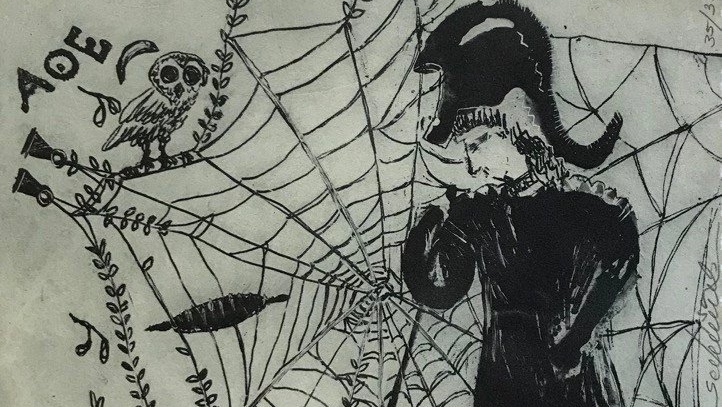

Warfare had a profound impact on life in the ancient world. Greek theater reflected this reality, as well as the experiences of its writers; all three of the surviving Greek tragedians (Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides) were influenced in some way by war. We’ll be taking a look at each of the three in turn, beginning with Aeschylus, and seeing how warfare shaped the beginnings of theater.

Aeschylus, chronologically the first of the three great ancient Greek tragedians, fought against the invading Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC; it’s also possible he fought at the Battle of Salamis ten years later. These wartime experiences gave him an insight into the true nature of power and informed his exploration of the tension between realism and idealism in drama. There is no question that Aeschylus placed a high value upon his service in the Greek army at Marathon. His epitaph, believed to be self-composed, makes no mention of his theatrical career, yet it describes his service in the history-making battle quite prominently: “The dead Aeschylus, son of Euphorion, the Athenian / this tomb covers in wheat-bearing Gela; / the grove of Marathon can attest his famed valor, / and the long-haired Mede who knew it well”. Evidently, Aeschylus viewed himself as a veteran first and as a playwright second.

The playwright’s military service did more than give him memorable material for an epitaph, however. Power is at the center of many of Aeschylus’ plays. The Persians, a historical play that centers upon the Persian loss at the Battle of Salamis, is unique in that the playwright himself may have participated in the story’s historical events; Strauss cites Ion of Chios, a contemporary of Aeschylus’ who claims that the playwright was indeed present at Salamis.