Written by Robert Gate, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

For millennia, dogs and people have shared a close partnership. No one is still ready to claim when and where the first dog was domesticated, but it is generally accepted that it was for hunting.

Thousands of years ago, men did not have big guns to aid them in hunting or protect from wild animals – this is why they needed dogs.

Canine friends delivered and were highly appreciated. Archaeologists discovered numerous stone columns and other objects that stand as evidence of the deep tie dogs and humans share.

Stay tuned to find out all there is to know about hunting dogs in the ancient world!

Hunting Dogs in Ancient Greece

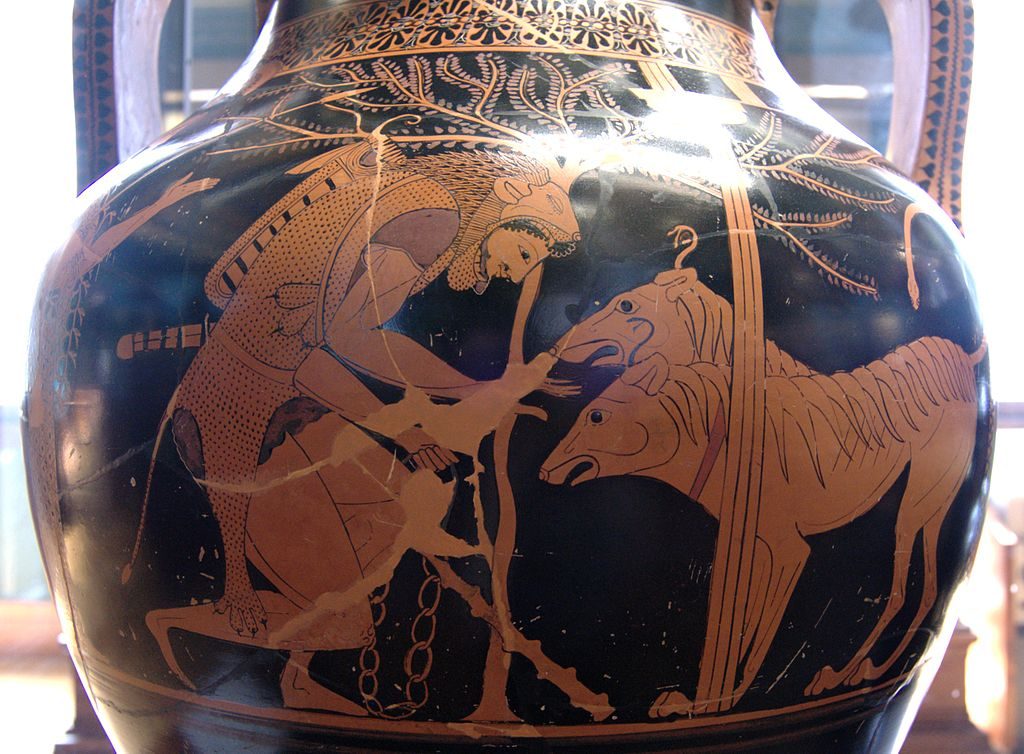

Heracles, chain in left hand, his club laid aside, calms a two-headed Cerberus, which has a snake protruding from each of his heads, a mane down his necks and back, and a snake tail. Amphora (c. 525–510 BC) from Vulci (Louvre F204). Source: Wikiwand.

Dogs were an important part of ancient Greece. They were protectors and hunters but companions as well. The Greeks were the first to invent spiked collars to protect their canine friends from wolves.

Greek goddesses Artemis and Hecate had dogs too. Artemis, being the goddess of the hunt, used them for hunting.

As far as the literature is concerned, the most famous Greek dog was the three-headed dog Cerberus, a guardian to the gates of Hades.

King Odysseus of Ithaka (from Homer’s Odyssey) had a loyal four-legged friend too – a dog named Argos.

He was the only one to recognize his master after twenty years of absence and was over the moon to see him again. When the king ignored his joy, the dog laid down and died of sadness.

What Breeds Of Dogs Were There In Ancient Greece?

This group of dog breeds is associated with the Molossi tribe that lived in Epirus in the northwest region of Ancient Greece.

They were mostly used as guardians and herding dogs but often helped hunters take down the big game. Mastiffs are considered to be their descendants.

This dog breed used to be bred as a scent hound. The shorthaired black and tan dogs were mostly used to track and chase hares in the southern parts of Ancient Greece.

These small white dogs are believed to be the ancestors of most terriers and other small dog breeds we can find in modern Western Europe.

- Laconian hound (Ichnilatis Lakonias)

The Laconian hounds were used for hunting deer and hares. They were a bit slow, though, and greatly relied on their sense of smell while hunting.

These small Greek domestic dogs are a bit larger than the Alopekis and have dropped ears. They can be both long and short-haired.

The ones with long hair are more often depicted on ancient artifacts. This breed of the Hellenic dog hunts birds and small game but can be a good companion too.

- The Cretan Hound (Kritikos Ichnilatis)

Present to this day, this breed from the island of Crete is considered to be one of the oldest breeds of hunting dogs in the world.

Cretan Hounds are multi-talented dogs – quick and agile, and with exceptional scent. They are the extraordinary hare and wild rabbit hunters but have guarding instincts too.

- Greek Shepherd (Hellenikos Poimenikos)

Greek Shep is a relatively large dog, with a solid body and massive head. It can take down almost any enemy and protect the flock but can sometimes be too stubborn to train.

Hunting Dogs in Ancient Rome

‘Cave canem’ (beware of the dog) mosaic. From Pompeii, Casa di Orfeo.

The Romans had various pets, but dogs were their favorite animal companions. Just like in Greece, dogs were depicted in works of art and literature.

Famous Latin poet Virgil praised them as guardians, while the writer Varro advised that every family should have both a watchdog and a hunting dog.

The Romans even believed that dogs could protect them from the unnatural forces. Their barking could warn people of any disembodied spirit preying on them.

What Breeds Of Dogs Were There In Ancient Rome?

Cane Corso is a quite impressive dog breed that is believed to originate in what is now known as south of Italy but used to be a part of an enormous Roman Empire. They belong to the Molosser family.

These dogs have a muscular body with a prominent guarding instinct. Being fit and powerful, they could take down big animals, so they were used for big game hunting such as deer or wild boars.

They could even hamper bears. The Roman army used them in battles too, and thus they are also often referred to as the Roman dogs of war.

This energetic breed of hunting dogs is believed to have been “imported” to the Roman Empire from the area of today’s Britain.

Agassians were small in size but armed with powerful claws and even more powerful noses.

They were excellent trackers and could mark almost any airborne scent. As such, they made indispensable hunting companions.

Imported from Greece, these large dogs with a small head and a long neck were mostly used for hunting. They made quite a great noise barking and chased the game vigorously.

Hunting Dogs in Ancient Egypt

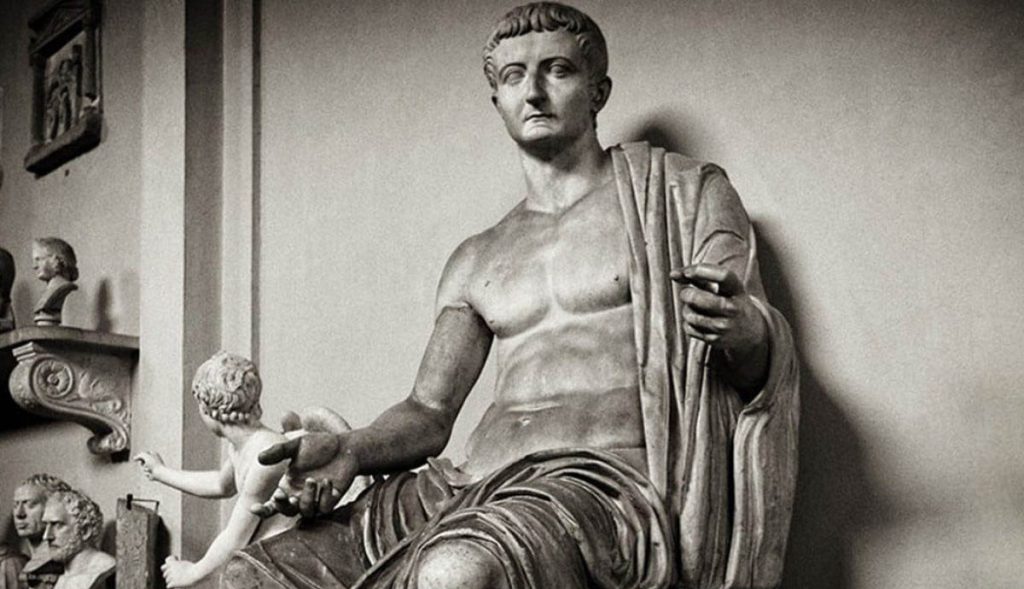

The Anubis Shrine; 1336–1327 BC; from the Valley of the Kings; Egyptian Museum (Cairo).

Even though Ancient Egypt is often associated with cats rather than dogs, Egyptians were “dog people” as well. Egyptologists found that dogs had been domesticated in the Pre-Dynastic era of Egypt.

Egyptians used dogs as Greeks and Romans did. They were companions, but also guardians, hunters, and weapons of war.

Canines were highly regarded, and as evidence of that, there are many hounds mentioned in mortuary texts and depicted in Egyptian art.

What Breeds Of Dogs Were There In Ancient Egypt?

This breed originated in Nubia. The name of the breed translates as “dog of the villagers.” The Basenji dogs were often family pets that doubled as hunting dogs for small game or guard dogs.

Even though the Greyhound origin is not entirely sure, there is evidence that this breed lived in both Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Greyhounds were mostly used for open-area hunting of big game.

The Ibizan, regardless of its current name, is a breed of Egyptian origin. It is considered to be a ‘typical’ Egyptian dog most often represented in Egyptian art.

This leggy visitor from the dawn of civilization was used for hunting small animals such as rabbits.

Pharaoh Hound is a dog you will most probably see depicted in hunting scenes of Egyptian art. It was a breed used as a sacrifice to Egyptian deity Anubis too.

This breed originated in Mesopotamia but was quite popular in Egypt later on. Salukis were used as both hunting dogs and companions.

Referred to as the dogs of the Egyptian kings, whippets were actually small and agile hunting dogs used for hunting in open terrain.

Other Hunting Dogs in the Ancient World

The best hunting dog was not easy to find in the ancient world, nor is it an easy task today.

Here are the breeds that were highly appreciated then and have survived to this very day:

Originated in Northern China (150 – 200 B.C.)

Originated in China (206 B.C.)

Originated in Siberia (1000 B.C.)

Originated in Alaska’s Norton Sound Region (around 1000 B.C)

Originated in Afghanistan (around 6,000 B.C.)

Originated in Central Africa (around 6000 B.C.)

Originated in Japan (around 8,000 B.C.)