Written by Lydia Serrant, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

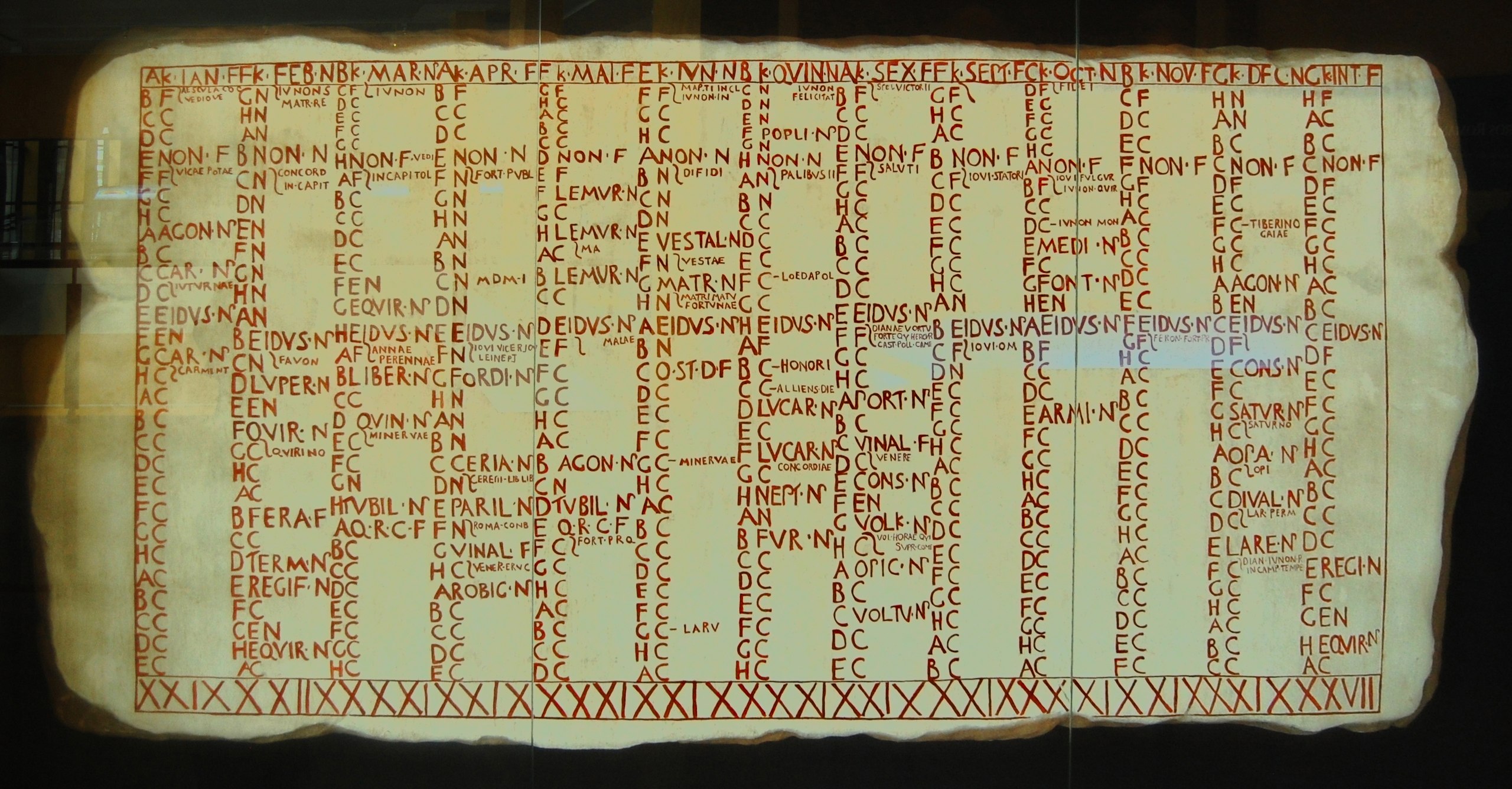

Athens, 424 BCE

It is daybreak on a Tuesday, and already the day is beginning to warm.

As usual, you wake up at sunrise to the sound of ritual singing coming from the courtyard. Your household slave has risen early and sings to the dawn as she prepares you a breakfast of wine, with yesterday’s slightly stale bread, for dipping.

You rise and put on your long plain white tunic before heading out. You decide to take breakfast outside, its barely 7 am and you like to sit with the dog and watch two of your goat’s graze in the courtyard as you dine.

Just like your father before you, you are a pottery craftsman of the middling sort. Your house is set on a busy side-street that runs from the west of Athens toward the inner city. It’s a good spot for passing customers on their way to the Agora.

The spacious mud-brick home is one story high and consists of several adjoining rooms that surround the rectangular courtyard. The bedroom and living quarters are sectioned onto the left-wing, where you can hear the children playing with their toy wooden horses as your slave watches over them.

The decor remains modest. The walls are washed with brilliant white paint and the earthen floors are covered with plain tiles and rushed mats. The few windows you have are covered by wooden shutters that allow in slithers of the morning sun.

The pottery workshop and the slaves’ sleeping quarters are arranged at the front side of the building facing the street. The workshop slaves begin work early. Already, you can hear the bellows as the furnace is stoked and the clatter of preparations for a day’s crafting and selling.

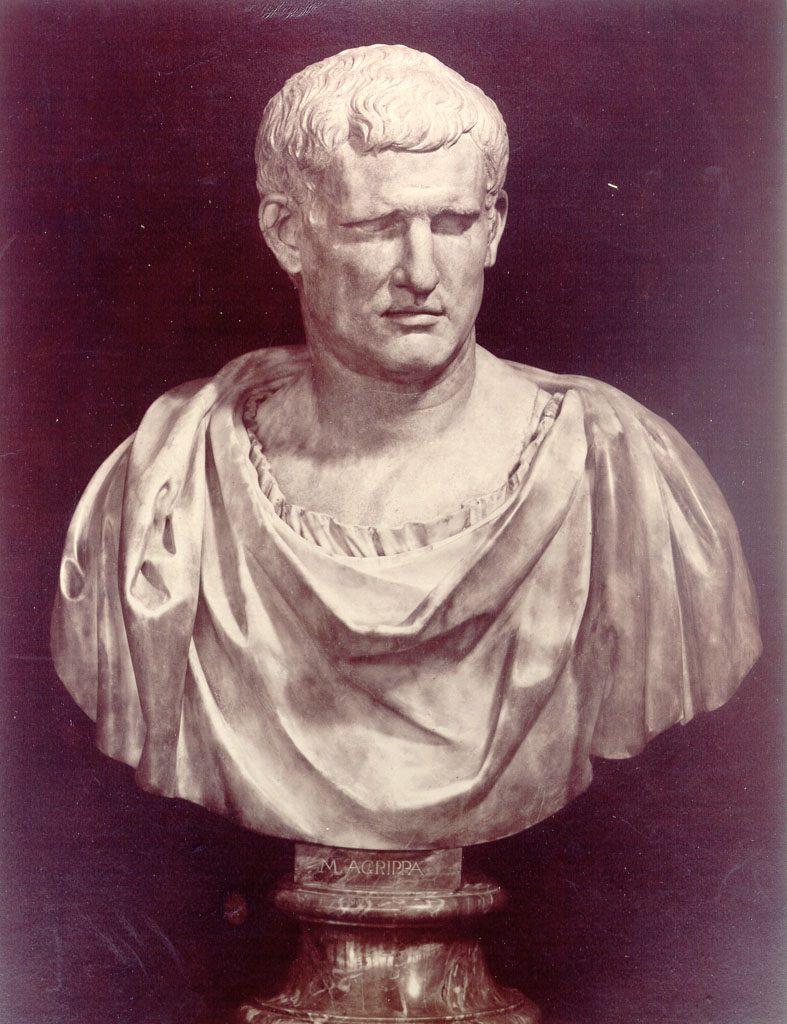

A master (right) and his slave (left) in a phlyax play, Silician red-figured calyx-krater, c. 350 BC–340 BC. Louvre Museum, Paris.

You spend the morning in the workshop overseeing the day’s work. You were fortunate enough to receive a commission from a lower member of the aristocracy for 10 decorative vases to adorn their newly built urban villa. The work is going well, and you leave early to attend an important afternoon engagement.

After an early lunch of bread, olive oil, and fish, you make your way out onto the busy Athenian streets and head

towards the Acropolis for the afternoon’s public Assembly. The street is hot and the trees are in full bloom. The people scurry back and forth, conducting their daily business.

You are running late, so you decide to take a short cut to avoid the busy main street. As you zig-zag your way across the cobbles, you are careful to avoid rivers of sewage and rats that plague the streets of the lower city.

You pass the cramped apartments and crowded housing and cover your face to avoid the stench. The smell is amplified by the midday sun, and the flies congregate in their swarms.

The Acropolis of Athens, seen from the Hill of the Muses

Faces peer out from behind shutters as you pass, and boys play in the streets with hoops and yo-yos. A small group of boys with dirty faces are huddled in the corner, just off the main street. They flick nuts into a make-shift circle made of sticks. As you turn onto the main road, the smallest boy screams with glee as his nut lands with precision.

The main road to the Acropolis is a stunning contrast to the dimly lit side streets. First off, the main roads are exceptionally clean. It is a crime to litter here, as this is the place where the Gods walk among men.

Rays from the afternoon sun reflect the white stone columns of buildings, flanked with beautiful banners of rich purple and blue. The statues of Greek Gods and heroes align the streets, expertly painted with vivid reds, yellows, browns, and whites.

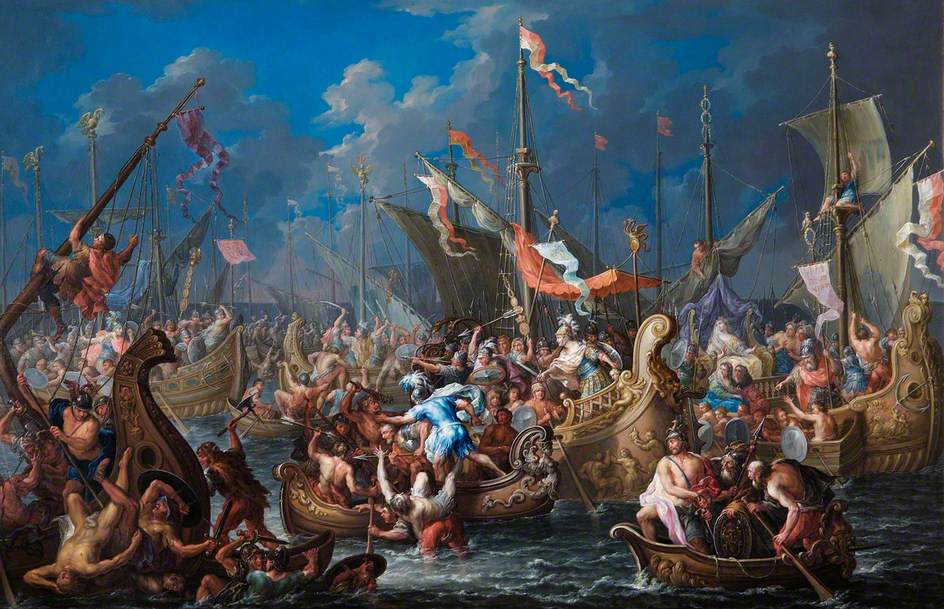

The Parthenon sits above you, dominating the landscape. Perched atop the Acropolis, the huge stone columns of the temple can be seen for miles, glistening in the midday sun. But that is not your destination. Today you head west and join the crowd heading for the Pnyx, the open-air auditorium that will play host to today’s Ecclesia Assembly.

The Pnyx (right), sits across from the Acropolis (left)

The Auditorium is packed with your fellow male Athenians, and you arrive just in time for the boule (leader) to take his place center stage. As one of the most senior members of the Athenian populace, he hushes the crowd and introduces the agenda of the day.

Today is a debate of particular significance.

The Athenian General Thucydides has lost the polis of Amphipolis to the Spartan Commander Brasidas. This is a major setback for Athens, and you have convened with 6,000 other Athenians to decide how to punish Thucydides for allowing this to happen.

The debate rages for hours, with each speaking member taking their turn. Those over 50 are heard first, some advocating death and others, forgiveness. You sit patiently and listen as each speaker sways the crowd from one emotion to the next. Eventually, a middle ground is settled, with a majority vote to exile the general from Athens indefinitely.

Thucydides Mosaic from Jerash, Jordan, Roman, 3rd century CE at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin

Dusk approaches, the sun begins to set and the crowds disperse.

You follow the crowd out and down

towards the inner agora marketplace. Some street performers still play on, and music fills the air. The market vendors have all but packed up most of their goods after a day’s trading, but the sweet smell of wine, meats, and incense linger.

Slaves with torches appear out of darkened doorways and light the lamps outside their master’s villas. The oil lamp light cascades across the cobblestones and dancing shadows accompany you on your way.

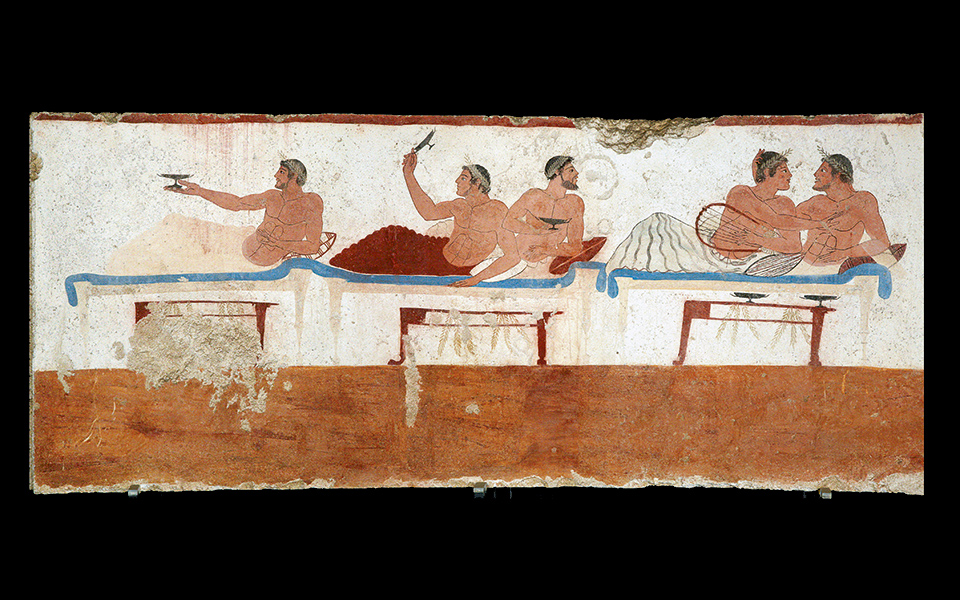

You arrive at the house of a friend, who has gathered 5 others in the Andron (men’s quarters) for an evening meal. You are served a dinner of wine, fish, legumes, quail eggs, olives, cheese, and bread. You raise your glass and give a toast to the Gods before the day’s events are discussed with fervor. The tone of the conversation escalates as more wine and water is passed around the table.

Having had your fill of good food and company you make the final journey of the day. You arrive at your home and find the torches lit and the room silent as you gather yourself and make your way to your sleeping quarters for a good night’s rest. You sink back into your pillow and your eyes flutter closed.

In what feels like no time at all, the dawn brings more song and a new day awaits.

Resources: