The Journey To Stoicism:

What is it, then, that arouses your discontent? Human wickedness? Call to mind the doctrine that rational creatures have come into the world for the sake of one another, and that tolerance is a part of justice… (Meditations, 4.2)

If I remember, then, that I am a part of such a whole, I shall be well contented with all that comes to pass; and in so far as I am bound by a tie of kinship to other parts of the same nature as myself I shall never act against the common interest, but rather, I shall take proper account of my fellows, and direct every impulse to the common benefit and turn it away from anything that runs counter to that benefit. And when this is duly accomplished, my life must necessarily follow a happy course, just as you would observe that any citizen’s life proceeds happily on its course when he makes his way through it performing actions which benefit his fellow citizens and he welcomes whatever his city assigns to him. (Meditations, 10.6)

Written by Aaron Smith, Instructor and Fellow, Ayn Rand Institute

[The Ayn Rand Institute has granted permission to Classical Wisdom Weekly to republish this article in its entirety, originally published in New Ideal, but does not necessarily endorse the images accompanying it or other content on this site.]

Over the past decade, the ancient Greek philosophy of Stoicism has seen renewed public attention. Recent popular books are selling Stoicism as a guide to self-mastery, psychological resilience, inner tranquility and happiness. There is William Irvine’s A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy (2009); Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle Is the Way: The Timeless Art of Turning Trials into Triumph (2014) and The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living (2016); and Massimo Pigliucci’s How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life (2017), to name a few. The philosophy has garnered the interest of CEOs, entrepreneurs, Silicon Valley tech workers and professional athletes.

There are good reasons, however, to steer clear of Stoicism as a philosophy of life. For although the Stoics raised important questions and issues, which these recent books are surfacing, the answers the Stoics offered to these questions are, in the end, deeply problematic.

Popular treatments of Stoicism universally stress the Stoics’ point that some things are “up to us” and other things are not up to us, and that it’s crucially important to distinguish correctly between these. Many of today’s advocates of Stoicism cite the famous Serenity Prayer to capture what they take to be the essence of this point: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

In his book The Daily Stoic, entrepreneur and media strategist Ryan Holiday pitches this point as follows:

The single most important practice in Stoic philosophy is differentiating between what we can change and what we can’t. What we have influence over and what we do not. A flight is delayed because of weather — no amount of yelling at an airline representative will end a storm. No amount of wishing will make you taller or shorter or born in a different country. No matter how hard you try you can’t make someone like you. And on top of that, time spent hurling yourself at these immovable objects is time not spent on the things we can change.1

There is something right in this advice, as far as it goes. The problem, however, is that Stoicism endorses determinism — the view that our actions and choices are necessitated by factors beyond our control. So, strictly speaking, nothing is up to us. And if nothing is up to us, what use is Holiday’s advice or the Serenity Prayer or anyone’s advice for that matter? There is no philosophically consistent answer to that question, except: “None whatsoever.”2

The chief theoretician of Stoicism, Chrysippus (ca. 280 – 206 B.C.), held that an action is “up to us” (or in our power), if it results, at least in part, from a cause that’s within us. But he also held that these internal causes (our judgments, values, motives and choices) are the inexorable result of a whole chain of prior (and equally inexorable) causes, which he called Fate. Whatever you do or decide to do — whether to get married, to leave your job or to order another round of sake — you had to do it; your decisions and actions were necessitated by factors preceding your birth. Despite his language of some things being “up to us,” Chrysippus is neither endorsing free will nor rejecting determinism.

The Stoics will often say that although events are not up to us, our judgments about events are. The implication, however, is that our judgments have nothing to do with what does or doesn’t happen to us. Every event is determined to occur precisely as it does, but we can choose to accommodate ourselves to events (rather than bemoan them) by viewing them as outside our control and, at least for the Stoics, as divinely ordered for the best. As one ancient writer, commenting on Stoicism, put the point:

They too [Zeno (334 – 262 B.C.) and Chrysippus] affirmed that everything is fated, with the following model. When a dog is tied to a cart, if it wants to follow it is pulled and follows, making its spontaneous act coincide with necessity, but if it does not want to follow, it will be compelled in any case. So it is with men too: even if they do not want to, they will be compelled in any case to follow what is destined.3

Stoic philosophy leaves us with no causal power to impact events, only at best the ability (so far unexplained) to voluntarily accept our leash and accommodate ourselves to the inevitable. This may provide a false sense of solace to some, but it isn’t exactly an empowering perspective on life.

For a philosophy to be useful as a guide, it must at least acknowledge that we have some genuine, volitional control over our actions and choices — actions and choices that make a difference to where we end up in life.

In his book How to Be a Stoic, philosopher of science Massimo Pigliucci seems to acknowledge this problem. But his way of handling this problem, and others, is to “update” Stoicism into something it never was.

Many of the particular notions developed by the ancient Stoics have ceded place to new ones introduced by modern science and philosophy and need therefore to be updated. For instance . . . the clear dichotomy the Stoics drew between what is and is not under our control is too strict: beyond our own thoughts and attitudes, there are some things that we can and, depending on circumstances, must influence — up to the point where we recognize that nothing more is in our power to be done.4

In addition to abandoning Stoic determinism, Pigliucci drops the central Stoic doctrine that a living, rational God pervades everything in the universe and providentially orders everything for the best — replacing it with atheism, Darwinian natural selection and a modern scientific notion of causation. Whatever the merits of these changes, what survives in How to Be a Stoic is not Stoicism.5

The pervasive determinism of Stoicism is likely what leads many of today’s popularizers to focus heavily on Epictetus (ca. A.D. 55 – 105), a Stoic of the later Roman Imperial period, who taught that the human faculty of judgment is completely free and unconstrained — unconstrained, says Epictetus, even by God. Whether Epictetus is introducing into Stoicism a notion of free will, however, is unclear.6

Relying on the Stoic doctrine that our souls are fragments of God, Epictetus asserted that just as God is completely free, so is our faculty of judgment. The question of how an unconstrained faculty of judgment could be consistent with the Stoic deterministic worldview does not seem to have been of particular concern to him.

The most likely interpretation is that Epictetus held that our judgment affects only our mental life, whereas events themselves happen as God (or Fate) would have them. In such a case, freedom, for Epictetus, is not a matter of possessing the ability to control or impact the events of our lives — it is about being free from the frustration and pain that comes from wanting events to occur other than they do.

As Anthony Long, one of the leading scholars on Epictetus, writes:

Our responsibility as individual persons is solely over the area in which we are capable of being autonomous — the ‘proper use of mental impressions’ (I. 12.34). Everything else is God’s business; it concerns us only to the extent that we adapt ourselves to it by understanding its rationale within the world’s inevitable and providential system.7

So, although the Stoics raise the important question of what is in our control and what is not, they are unable to offer anything close to a satisfactory viewpoint on this issue.

Advice about distinguishing between what is up to us and what is not (and acting accordingly) rests on, and only makes sense in the context of, the fact that human beings have free will. Embracing this fact requires rejecting Stoicism’s basic view of reality: its deterministic framework, including its exhortations to willingly accommodate ourselves to events.

Consider another aspect of Stoicism that recent popular books are emphasizing. The Stoics insist, rightly, that your psychological well-being is deeply affected by what you value, and so you need to think carefully about what is truly valuable in life and what is not.

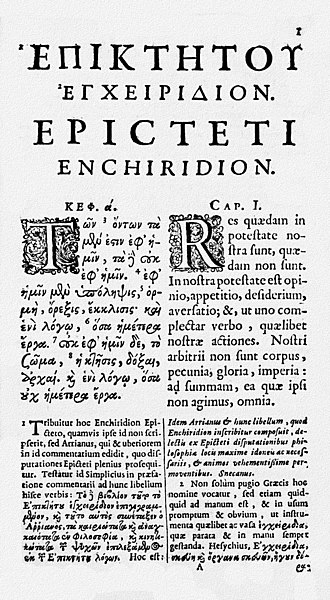

Chapter 1, page 1, of the Enchiridion of Epictetus, from the 1683 edition in Greek and Latin by Abrahamus Berkelius (Abraham van Berkel).

In his book A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy, professor of philosophy William Irvine expresses the point, from a Stoic perspective, as follows:

As Epictetus puts it, “What upsets people is not things themselves but their judgments about these things.” To better understand this claim, suppose someone deprives me of my property. He has done me harm only if it is my opinion that my property had real value. Suppose, by way of illustration, that someone steals a concrete birdbath from my backyard. If I treasured this birdbath, I will be quite upset by the theft. . . . If I’m indifferent to the birdbath, however, I will not be upset by its loss. . . . My tranquility will not be disrupted. . . . Do the things that happen to me help or harm me? It all depends, say the Stoics, on my values. They would go on to remind me that my values are things over which I have complete control. Therefore, if something external harms me, it is my own fault: I should have adopted different values.8

Of course, if you accept determinism, then you have no control over what you value, and this advice is useless. Even if you grant the baseless idea that events are not up to you, but your value judgments about them are up to you, the Stoic view of what you should and should not value is as crippling to your life as its deterministic worldview.

As Irvine notes above, the Stoics hold that you should only value things over which you have control — and, for the relevant Stoics, this means primarily your judgments and, derivatively, your resulting emotions and moral character. If you value anything that is not under your control, you’ll cherish things fate may take from you at any moment, and that sets you up for a life of pain and frustration. As a result, they hold that the whole range of life-sustaining and life-enhancing values — wealth, art, technology, career success, family, etc. — must not be thought of as having any genuine value — and you mustn’t become attached to them or care for them as if they are truly important.9 To maintain this perspective, the Stoics advocate training yourself regularly to see such values as unimportant.

Marcus Aurelius (A.D. 121 – 180) gives us a striking (and disturbing) example of such practice from his own life:

How useful, when roasted meats and other foods are before you to see them in your mind as here the dead body of a fish, there the dead body of a bird or a pig. Or again, to think of Falernian wine as the juice of a cluster of grapes, of a purple robe as sheep’s wool died with the blood of a shellfish, and of sexual intercourse as internal rubbing accompanied by the spasmodic ejection of mucus. What useful perceptual images these are! They go to the heart of things and pierce right through them, so that you see things for what they are.10

As Epictetus famously puts it:

Whenever you are devoted to something, don’t regard it as irremovable but as belonging to the class of things like a jar or a drinking glass so that when it is broken you remember what it was and are not disturbed. So in the case of love, if you kiss your child or your brother or your friend, never let your thoughts about them go all the way, and don’t allow yourself to be as elated as your feeling wants, but check it and restrain it . . . . Furthermore, at the very moment you are taking joy in something, present yourself with the opposite impressions. What harm is it, just when you are kissing your little child, to say: Tomorrow you will die, or to your friend similarly: Tomorrow one of us will go away and we shall not see one another anymore?11

From a psychological perspective, this approach to values is fundamentally an attempt to avoid pain, frustration and loss in a world in which everything you might want or love or care about is short-lived, easily lost and precariously kept. To the extent that you invest yourself in things over which you have no control, they hold, you will be perpetually unhappy.

Now, it is true that intensely valuing life and the things you love involves the possibility of pain, loss and disappointment, sometimes acute. Stoicism’s advice is to steel yourself against that possibility by killing your capacity to value. This is not a recipe for inner peace; it is a recipe for destroying any possibility for happiness.

Realizing and accepting that your lifespan is limited is all the more reason to value your life intensely and to wring from it every moment of joy you can. This requires effort, emotional investment and the risk of pain. Yes, someday your child will die, but that does not mean that while she’s alive you should withdraw or even temper your attachment to her. On the contrary, to keep yourself from loving “too much” is to keep yourself from loving. To temper emotions such as love or elation or joy or passion is to kill one’s capacity to live. The Stoic viewpoint on values is, in the end, anti-value.12

In this regard, Marcus Aurelius’ private journal — referred to today as his Meditations — provides moving (if indirect) witness. On the one hand, he devoutly affirms the Stoic doctrine that everything that happens is divinely ordered for the best. But, given his Stoic approach to valuing, he finds that in this best of all possible worlds there is little to love. He frequently comments on the vanity of existence, the insignificance of life, the sheer pointlessness of so much of what makes up human existence. “Altogether, human affairs must be regarded as ephemeral, and of little worth: yesterday sperm, tomorrow a mummy or ashes.”13

In the introduction to his translation of the Meditations, associate professor of classics Gregory Hays rightly notes that “Marcus does not offer us a means of achieving happiness, but only a means of resisting pain.” Hays continues:

The Stoicism of the Meditations is fundamentally a defensive philosophy; it is noteworthy how many military images recur, from references to the soul as being “posted” or “stationed” to the famous image of the mind as an invulnerable fortress (8.48). Such images are not unique to Marcus, but one can imagine that they might have had special meaning for an emperor whose last years were spent in “warfare and a journey far from home” (2.17). For Marcus, life was a battle, and often it must have seemed — what in some sense it must always be — a losing battle.”14

Marcus Aurelius adopted a philosophy that promised resilience and inner peace in what he regarded as a hostile world. But it was a false promise. From the perspective of philosophical essentials, the Stoic approach to life and valuing that he adopted was antithetical to happiness and set against everything that makes life worth living. Judging from the Meditations, it deadened him (and would deaden anyone) toward life.

One might ask: If Stoic philosophy, taken seriously, is that bad, can’t we adopt a kind of “cafeteria Stoic” approach picking up the few bits we find useful, modifying others, discarding the rest?

The answer is: Yes, of course we can. But it’s important to know, explicitly, that this is what we’re doing. Because to the extent that we’re taking this approach, we’re not practicing Stoicism. We are abandoning it and relying implicitly on different (and often unidentified) philosophic ideas. To really get the value out of philosophic guidance, we would need to identify our implicit ideas and integrate them to see if what we have at the end is a functional framework for living, or merely an inconsistent grab bag of useful tips, unsupported principles and falsehoods, which cannot move us consistently toward happiness.

To take seriously and to benefit from advice about what is up to us and what is not, we would need to reject any form of determinism (Stoic or modern) and embrace the fact that we have free will — and that requires thinking carefully about what precisely is within our power to change and what isn’t so that we can formulate our goals and orient our efforts rationally.

Likewise, to benefit from advice about pursuing genuine values, we would need a rational conception of what to value — not one that is wedded to a deterministic worldview in which, allegedly, the best we can do is accept our fate and unplug from our values to minimize pain. In fact, we would need to pursue precisely the kinds of life-sustaining, life-enriching values that Stoicism urges us to be indifferent to.

My point, in the end, is that contrary to the Stoic worldview, we live in a universe in which the achievement of genuine happiness is possible, provided we understand what is required to achieve it and we put forth the thought and effort it requires. And thus life can be, and properly ought to be, an ambitious and unrelenting quest for personal happiness and joy because the pursuit and achievement of these values is what makes life meaningful and worth living.

Footnotes