Livia and her son Tiberius, AD 14–19, from Paestum, National Archaeological Museum of Spain, Madrid.

Head of Augustus as Pontifex Maximus, Roman artwork of the late Augustan period, last decade of the 1st century BC

Livia and her son Tiberius, AD 14–19, from Paestum, National Archaeological Museum of Spain, Madrid.

Head of Augustus as Pontifex Maximus, Roman artwork of the late Augustan period, last decade of the 1st century BC

Aeschylus

Draco

Empedocles

Chrysippus

Pythagoras

Antiphanes

Crassus

Human, All Too Human

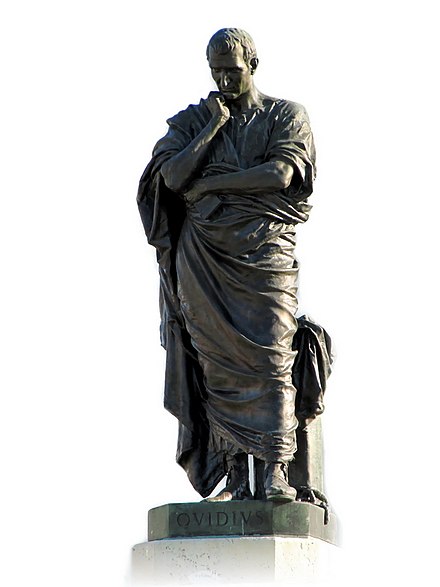

Statue (1887) by Ettore Ferrari commemorating Ovid’s exile in Tomis (present-day Constanța, Romania)

An illumination of the story of Pyramus and Thisbe from a manuscript of William Caxton’s translation of the Metamorphoses (1480)—the first in the English language

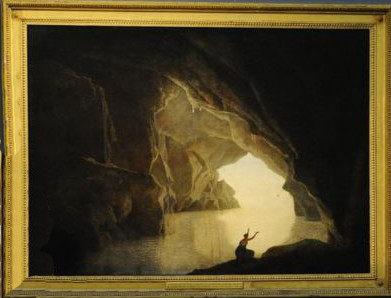

Julia the Younger was imagined in Grotto in the Gulf of Salerno by Joseph Wright of Derby in 1774.

‘Ovid among the Scythians’ (1862) by Eugène Delacroix.

Scythians at the Tomb of Ovid, by Johann Heinrich Schönfeld

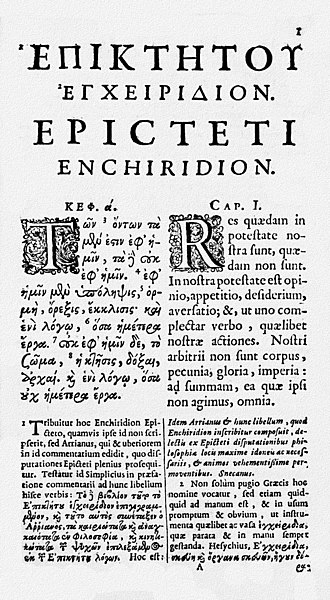

“Some things are in our control and others not. Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.” ~ Epictetus, Enchiridion

“You may be unconquerable, if you enter into no combat in which it is not in your own control to conquer.”

Chapter 1, page 1, of the Enchiridion of Epictetus, from the 1683 edition in Greek and Latin by Abrahamus Berkelius (Abraham van Berkel).

“But, for your part, don’t wish to be a general, or a senator, or a consul, but to be free; and the only way to this is a contempt of things not in our own control.”

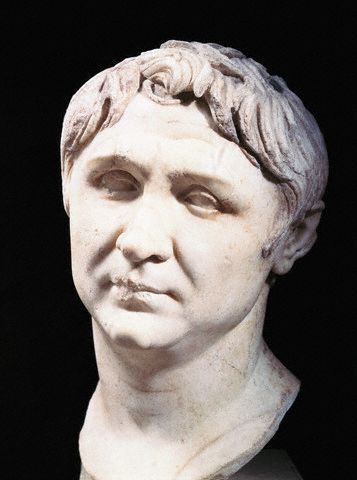

ca. 1st century B.C. — Bust of Pompey

After Cato’s suicide, his ideas lived on and he continued to inspire Republicans, despite Caesar’s victory. In particular, he was a great influence on the assassins of Julius Caesar in 44 BC. Indeed, Cato the Younger had been the guardian of Marcus Brutus, perhaps the best known of the assassins.

Cato was in many ways an unattractive figure; he was stubborn, intolerant and grim. However, he was also an honest man who was dedicated to the ideals of Republican Rome. His commitment to Stoicism was exemplary and he did much to popularize this philosophy in the Roman Empire. To many, he became a model of virtue and represented all that was best in Classical Civilization. Later writers, such as Cicero and Lucian, praised him in their work, while Dante celebrated his memory in the Divine Comedy.

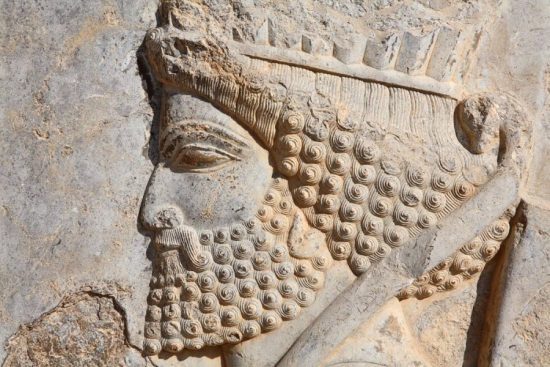

In an age of heroes and gods, when priests in lofty temples decided people’s fates, there ruled a king who challenged the might of both the Egyptian and Greek empires. The grandson of Cyrus the Great, Xerxes became King, son of Queen Atossa and King Darius I, but his rule was not always so noble or successful.

Coming to Power

It is the year 486BC and King Darius I, the great Persian King of Kings, is preparing for another war with Greece. Unfortunately, at the grand age of 64, his health was declining and so from his royal palace in Persepolis, King Darius named Xerxes his heir. King Darius died shortly thereafter, throwing his heir Xerxes and Artobazan, his older brother, into uncertainty.

Artobazan, the first-born son, claimed the crown as his birth right. However, Artobazan was born to Darius by a commoner. The exiled Spartan king Demaratus advised Xerxes that Artobazan’s claim had no foundation; as it was Xerxes who was born to the King and Atossa, the Queen and the daughter of King Cyrus the Great.

This argument proved solid, Xerxes was hence recognised as the only legal heir to the throne of Persia, succeeding his father and being crowned sometime between October and December of 486 BC.

Thrust into War

With the crown placed on his head, Xerxes was immediately besieged with thoughts of war; of his father’s war with Greece, and with an uprising and revolts in Egypt and Babylon as a result of his father’s building efforts of the royal palaces in Susa and Persepolis.

The revolts were quashed swiftly by the might of the Persian forces, and this led Xerxes to appoint his brother, Achaemenes, as satrap over Egypt. But no sooner had the dust settled than Xerxes was thrust back into turmoil when he outraged his Babylonian subjects.

As King, he was required to grasp the outstretched hands of the golden statue of Marduk on New Year’s Day. Xerxes, however, had violently confiscated and melted this idol, which incited the Babylonians to revolt not once, but twice, in 484 BC and again in 482 BC.

With Egypt and Babylon back under control, Xerxes then returned his attention to his father’s invasion and punishment of the Greek mainland. This punishment was the result of interference during the Ionian Revolt of 499 BC to 493 BC.

Persian soldier (left) and Greek hoplite (right) depicted fighting, on an ancient kylix, 5th century BC

In 483 BC Xerxes began preparing for his campaign. The Xerxes Canal was constructed, allowing them to store provisions through Thrace as it cut through the isthmus of Mount Athos. With two pontoon bridges across the Hellespont (today known as Dardanelles),

Xerxes was ready for war with his pan-Mediterranean army, with soldiers from Phoenicia, Assyria, Egypt, Thrace, Macedon, and many other Grecian states. Xerxes army was a force to be reckoned with; he was poised for victory.

A Twist of Fate

Yet, Xerxes’ mighty victory never came. Instead, according to Herodotus, his initial attempt was thwarted, not by an army, but by nature. A terrible storm swept through the isthmus and tore apart the pontoon bridges, demolishing the papyrus and flax cables that held the bridges together.

Xerxes, enraged, then ordered the Hellespont to be whipped 300 hundred times and commanded that fetters be thrown into the water. How this was going to punish the unruly weather is anyone’s guess, but it apparently worked, as his second attempt to cross was successful.

This assault would come to be known as the Carthaginian invasion of Sicily, and its effect was to prevent any support from Agrigentum and Syracuse and forced Thessaly, Thebes and Argos to join the Persian side. It was a resounding success.

From here, in Sardis in 480 BC, that Xerxes would set out with the greatest the world had ever seen. Herodotus estimated the army to about one million in number, with the elite force known as the Immortals, so named, as their number was not permitted to drop below 10,000 men. The size of the Persian army has been given a serious review in modern times, with the estimated size being suggested at closer to 60,000 fighters.

The Zenith of Xerxes

The battle at Thermopylae is well known by all historians and movie fans alike; the heroic tale of King Leonidas leading his 300 Spartan warriors. There in stony crags, they held back the onslaught of the Persian army but were ultimately defeated due to betrayal by a fellow Greek by the name of Ephialtes.

Xerxes assault on Thermopylae is the stuff of legends, so too was its lesson: when you hit a wall, if you can’t go through it look for a way around, under, or over it. Which is what he did by taking the secret pass through the mountains. Once through the mountains, the Persian army continued their attack and were aided by a storm that wrecked the Greek ships at Artemisium. Faced with this defeat, the Greek armies retreated.

Xerxes refused to slow his progress. His eyes were set on fulfilling his father’s punishment of the Athenians. The city, having been abandoned by its inhabitants for the island of Salamis, gave little defence.

With Athens in his grasp, he ordered its destruction; in 480 BC the city was burnt. The fires raged to such a degree that it left an indelible mark; a mark know by us today through an archaeological attested destruction layer, known as Perserschutt. Xerxes now controlled all of mainland Greece north of the Isthmus of Corinth.

The Turning Tides

Whether his pride took over, or he became so arrogant he would not listen to his advisors, Xerxes fell for a trap. The Greeks, under the Athenian general Themistocles, tempted the invaders into a naval skirmish in the Saronic Gulf by subterfuge. The plan was to block the narrow Straits of Salamis and cut off the Greek navy.

Here, Xerxes’s navy was unprepared for the unfavourable weather conditions, and within hours the alliance of Greek city-states was able to outmaneuver and defeat the invading army. Despite being heavily outnumbered, the Greeks managed to overcome the Persians, as their ships were smaller and more agile in the tempestuous waters.

With his navy relegated to the bottom of the seafloor, Xerxes retreated to Asia with a large contingent of his army. He left Mardonis, a leading commander in his army, to complete the assault.

However, this would not be so. The following year the remnants of the Persian army launched an attack at Plataea while the Persian navy attacked Mycale. Both of these battles were disastrous, with the Greeks scoring decisive victories.

Rebuilding His Image

After the resounding defeat in Greece, Xerxes returned to Persia and focused instead upon completing the royal palaces at Susa and Persepolis, along with many smaller but highly detailed building projects within these complexes.

These achievements include the Gate of All Nations, the Hall of a Hundred Columns at Persepolis, the Apadana, the Tachara, the Treasury, along with maintaining the Royal Road and completing the Susa Gate.

While his military achievements were a mixed bag, his architectural endeavours were all successes, with some still in existence to this day.

The Gate of All Nations (Old Persian : duvarthim visadahyum) also known as the Gate of Xerxes, located in the ruins of the ancient city of Persepolis, Iran.

Betrayal and Murder

The summer of 465 BC saw the king cut down, assassinated by the royal bodyguard Artabanus and a eunuch Aspamitres. The political figure, Artabanus, was the protector of the king but had been scheming for some time to dethrone the Achaemenids. He had placed his sons in positions of power and waited for the time to strike.

Xerxes murder was only part of the plan. Artabanus’ plot also involved murdering the heir, Crown Prince Darius. There are some contradicting accounts of exactly who was killed first, but the plot was successful. Both king and heir were dead.

Artabanus’ plan backfired though, and when prince Artaxerxes uncovered the plot, no doubt with the help of Megabyzuz who had switched sides, retribution was sought. Artaxerxes came after Artabanus and all of his sons. This decisive action, along with the defection of Megabyzus, is attributed with having saved the line of the Achaemenids.

Xerxes’ Impact

Xerxes and his achievements have been depicted for thousands of years. As early as Aeschylus and his play ‘The Persians’, Xerxes was being immortalised. George Frideric Handel’s protagonist Serse is based on the Persian king, and the Italian Poet Metastasio romanticised the story of the murder of Xerxes, Crown Prince Darius, and the ascension of Artaxerxes in the libretto of his Artaserse.

Xerxes even appears in the Bible, where he was identified as King Ahasuerus in the Book of Esther, inspiring the painting Esther Denouncing Haman to King Ahaseurus by Ernest Normand. He has also been portrayed in films (perhaps unflatteringly) such as The 300 Spartans (1962) and 300 (2006).

Whilst his departure from the world was as abrupt as his ascension, Xerxes’ impact is undeniable. Without him, we would not have the incredible story of the courage of the Spartans under Leonidas, nor the Perschutt of Athens. We would be without the Gate of All Nations, or the Royal Road that would prove its value for generations to come. Xerxes’ life and reign was short by today’s standards, but his legacy has lasted, and will last, for millennia.