Witches of the Ancient World

by Ed Whelan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

When we think of witches, we think of Hallowe’en and scary movies. What many people don’t realize is that witches have been around for a lot longer than any of those things, stretching all the way back to ancient Greece and Rome…

In fact, many ancient cultures have female figures that can be accurately characterized as witches. The witch is a cultural construction: someone (almost always a woman) who uses sorcery to accomplish some goal or to afflict evil. In the ancient world (as indeed, the modern world), they were often the embodiment of male fear about female sexuality and power. Greek society was patriarchal : women had to be subordinate to males. If they were not controlled, it was believed (by the men) that they were capable of all sorts of evil. The Greeks believed that a witch could commit any evil, such as Medea, who killed her own children to avenge herself on their father, Jason

Furthermore, like many other pre-industrial societies, the Graeco-Roman World was one where the belief in magic was universal: it was simply part of the everyday life of many people. Individuals often ascribed disasters to witches who were capable of what would today be termed black magic.

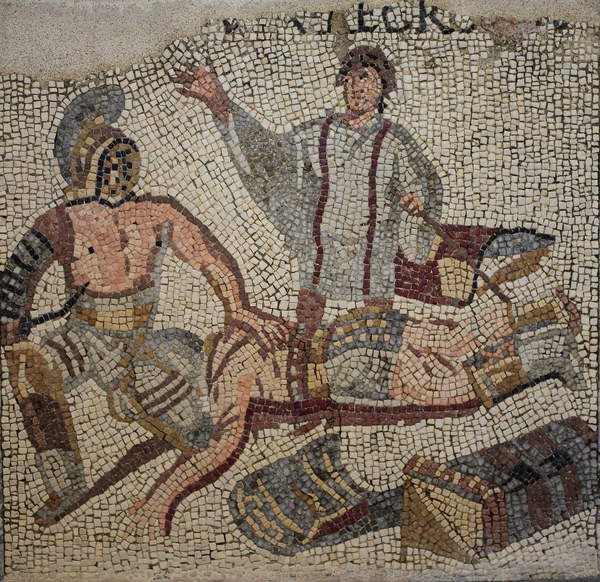

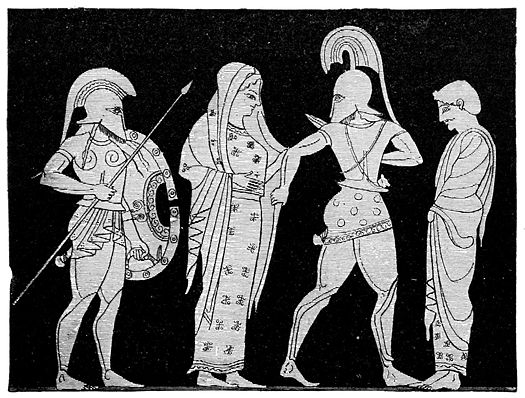

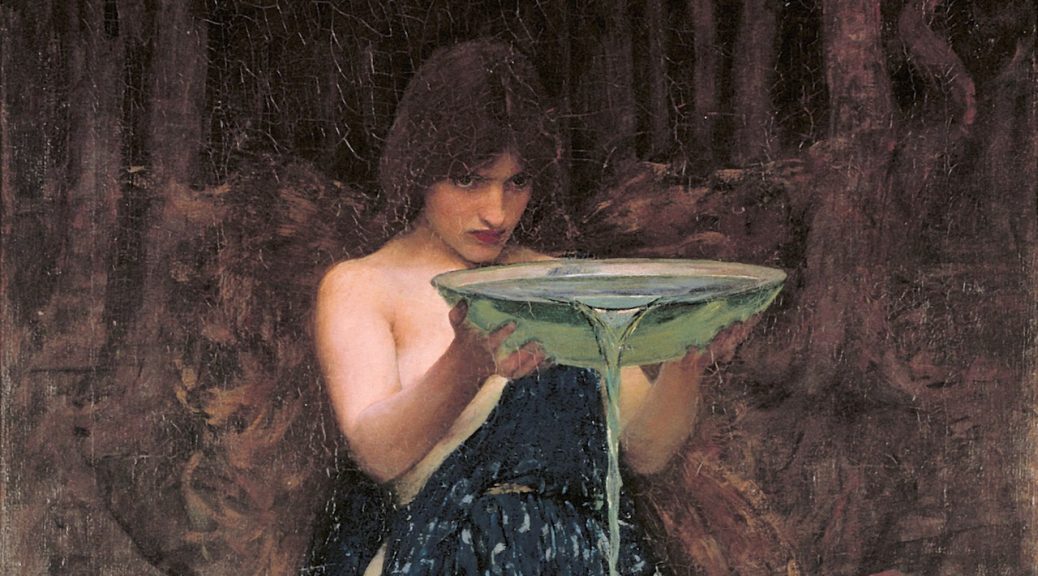

So, there are, indeed, many representations of women engaging in sorcery in Greek literature: as far back as Homer there are ancient Greek references to female figures who cast spells. Hecate was revered as the goddess of magic and witchcraft, for instance. One of the distinguishing characteristics of Greek witches was that they were sexually unrestrained and predatory. A good example of a Greek witch is Circe, who in her pursuit of Odysseus, turned his men into swine, and kept the hero a virtual prisoner on her island. Circe. Like other witches, she engaged in pharmakon: the concoction of brews and potions. Another example of a witch from Greek mythology is Lamia, who after her children were killed by Hera, became a child-eating monster. In this tale we see the origin of many of the tales of sorceresses who eat children.

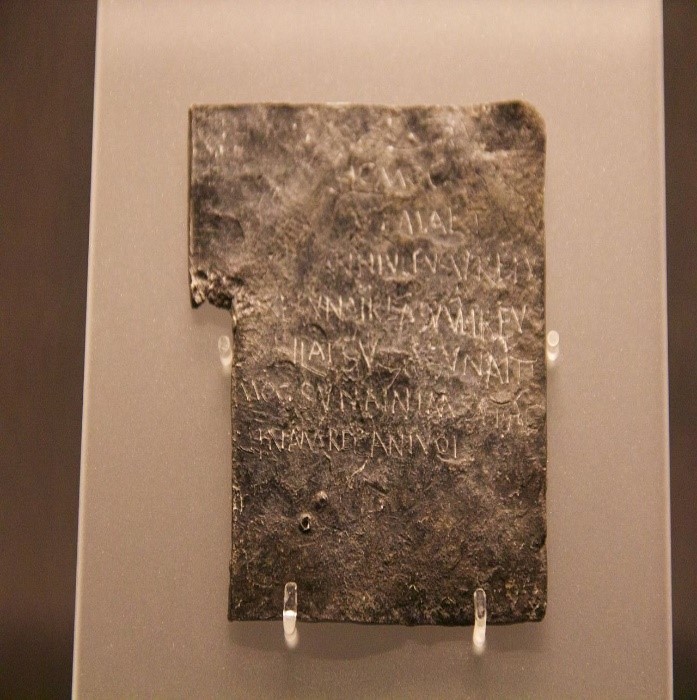

The Romans appear to have been even more concerned about witchcraft than the Greeks. In the law of the Twelve Tables, the casting of spells which harmed crops, cattle and persons were prohibited. Witchcraft was a capital crime in the Roman world, and witches could be burned or buried alive. Curse-tablets were very common. These were artifacts that were believed to curse or harm victims, and were often purchased from women who could be interpreted as witches. Many witches, especially in the Roman world, were associated with poisons. Females who made potions and perfumes could be condemned as witches. Some Latin sources refer to women who engaged in necromancy, and even some who were believed to be shapeshifters. There were both male and female witches or magicians in Rome, and they were often persecuted for casting spells on the emperor. As Pliny the Younger wrote: everyone was afraid of witches and their spells. Romans began the first known witch hunts in the Imperial period, long before the Christians began burning witches.

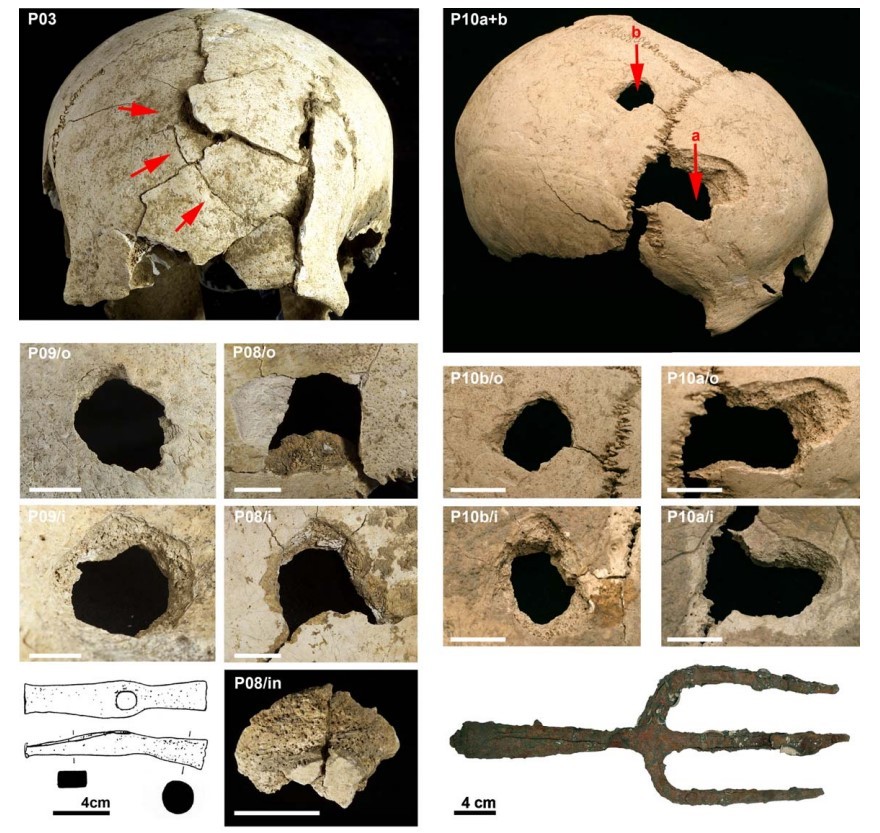

In contrast to the Greek depictions of witches, the Roman witch was motivated by pure spite and malice. One of the earliest depictions that we have of Roman witches is from the poems of Horace. He depicts two sorceresses with pale skin, long nails and wild hair, which are very similar to modern depictions. They are showing burying a wolf’s head under a full moon to conjure up the dead and make them do their bidding. One of the most famous witches in Latin literature was Erichtho in the Pharsalia by Lucan. In this Epic, she desecrates the corpses of the dead and murders people. She is shown as even terrorising the spirits of the realm of the dead, by screaming down the throats of their corpses on earth. It was widely believed that witches murdered children and used portions of their body for spells. One of the most distinctive of all Roman witches were the so-called Strix or owl-witches. They were women who embodied the screams of birds of ill-omen, who would devour the flesh of children. They often abducted infants and substituted them with straw dolls.

While witches are often portrayed by male classical authors as evil, many people may not have regarded them as so. Many women with knowledge of herbs and potions sold love potions and engaged in what we might term ‘white magic’. These ‘witches’ were often seen as healers and respected members of their community. The Classical depiction of witches is much influenced by male misogyny: those whom many elite males referred to as witches were often ‘wise women’ whose help was often sought by the poor and other women. It is likely that many of the representations of the witch was motivated by male fears of female sexuality and were used to justify the existing patriarchy.

So, maybe witches aren’t monsters after all, and are just misunderstood. Or maybe I’m under a spell!

References

Luck, G. ed., 2006. Arcana mundi: magic and the occult in the Greek and Roman worlds: a collection of ancient texts. JHU Press.