The story sounds like a Dan Brown thriller:

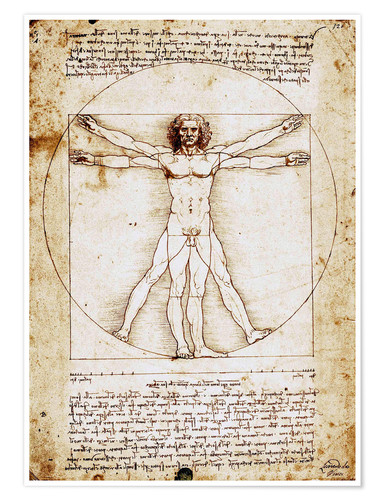

Leonardo Da Vinci’s notebooks contain a skillfully executed, albeit curious image. A man with two sets of arms and legs poses in the center of a circle and square. With one set of arms forming a V and one set of legs out-splayed, the figure’s soles and fingertips define the circumference of the circle. With the other set of arms outstretched and legs straight, the figure defines the perimeter of the square.

Known in Italian as L’Uomo Vitruviano—the Vitruvian man—the c. 1490 image is perhaps the most recognizable of all Leonardo’s sketches. A simple internet search reveals literally hundreds of reproductions, adaptations, and parodies. It may come as a surprise that this sketch, unlike others, did not spring from Leonardo’s fertile imagination, but was designed to illustrate someone else’s ideas:

[I]f a man be placed flat on his back, with his hands and feet extended, and a pair of compasses centred at his navel, the fingers and toes of his two hands and feet will touch the circumference of a circle described therefrom. And just as the human body yields a circular outline, so too a square figure may be found from it.

Vitruvian Man, Leonardo da Vinci. Year c. 1490

This passage appears in Book III, chapter 1 of De Architectura, the only comprehensive work on architecture to survive from Classical Antiquity, authored by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio. It’s an interesting concept, to be sure, but what about it would inspire Leonardo to produce one of his most evocative drawings?

There is indeed much more to this story: behind the Vitruvian man stands an enigmatic builder, a learned manuscript, a legendary name, and cultural prestige.

Vitruvius qui de architectonica

So, who was the original Vitruvian man? Who was Marcus Vitruvius Pollio? The facts of his existence are few and the questions are many. To begin, even his name is a conjecture. His praenomen was most likely Marcus, but we’re not certain. The cognomen Pollio is also only probable. Faventinus, an architect writing in the 3rd century CE, is believed to be the first writer to use Vitruvius’ full name. However, an alternate theory suggests that he may have been referring to two separate individuals: a Vitruvius and a Pollio.

Presumed portrait of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80/70 B.C. circa-25 B.C.)

As with his name, almost everything else we think we know about Vitruvius is a matter of more-or-less certain extrapolation from brief autobiographical scraps in his De Architectura.

Of his background and upbringing, Vitruvius says only that his family was able to give him a good education. Similarly, when he makes observations about the preferred education for architects, he is clearly referring to his own. After all, in the first chapter of Book I, Vitruvius says an architect needs a wide-ranging education, which is precisely the sort of education he claims for himself in the preface to Book VI.

We would expect an architect to have working knowledge of mathematics, materials, and physics. But what about pre-Socratic philosophy? Indeed,

Empedocles’ elemental philosophy is essential to the city planner. Like many Classical thinkers, Vitruvius derived from Empedocles the belief that differences between human groups reflected different elemental mixtures. The blend of elements in the Gauls, for instance, was vastly different from the corresponding blend in the Egyptians. Therefore a building site that would be healthy for one group would be harmful to another. Put in practical terms, Vitruvius held that a wise city planner should know how to select particular environments that promote the general health of the citizenry.

In other parts of De Architectura, Vitruvius expresses familiarity with Eratosthenes’s calculations of the circumference of the earth and Pythagoras’ philosophy of harmony. Needless to say, Vitruvius also owes much to Aristotle. On a basic level, Vitruvius’s statement about the three divisions of architecture —usefulness, durability, and beauty—merely specifies Aristotle’s assertion that the goal of all human endeavors is some definable “good.”

Frontispiece of De Architectura

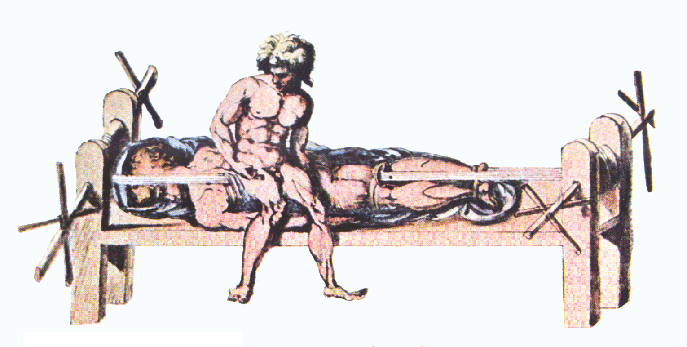

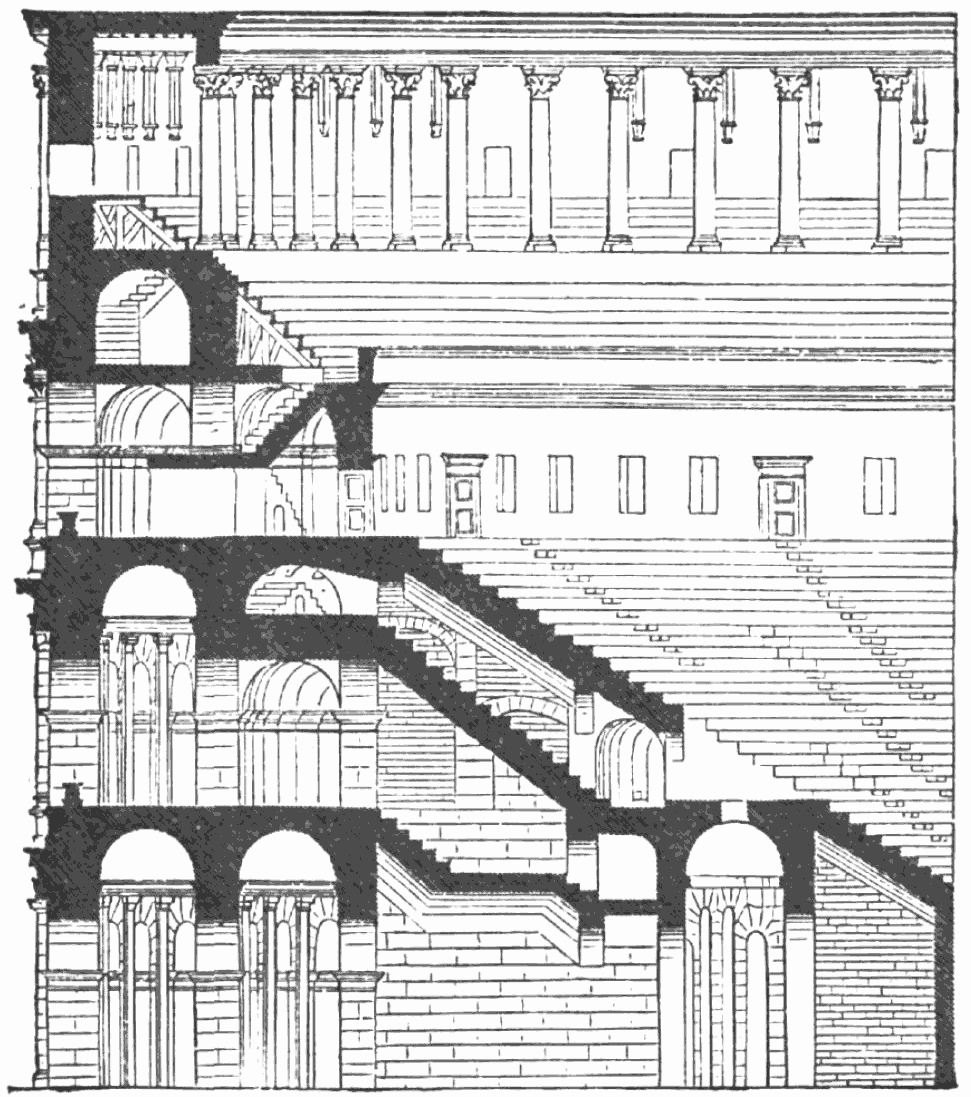

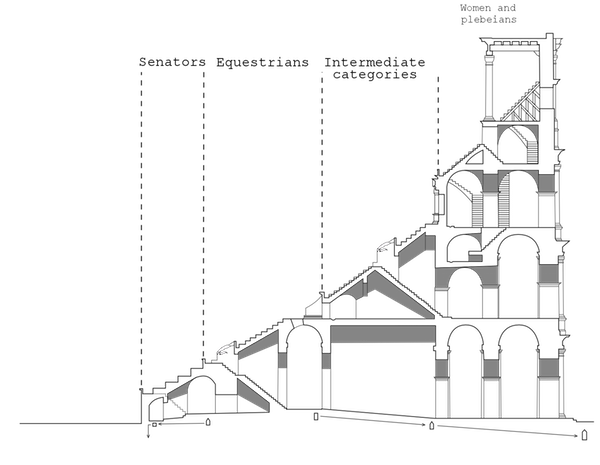

No mere theorist, Vitruvius states that much of his know-how was learned hands-on. “I myself know by experience,” he remarks. In parts of the work, he gives details on construction techniques, materials, and the machines used in building. He states that he superintended the construction of a basilica in Fano. Occasionally, he gives details that seem to come from the workshop, such as his claim that bricks should be dried for a full five years before use, whereas cut stone need only be seasoned for two.

In several passages, Vitruvius also mentions his military service. He says he built artillery pieces for Julius Caesar, and gives detailed instructions for such weapons as ballistas and scorpions. He even refers familiarly to how experts evaluate whether these weapons are well made: the control ropes vibrate at a certain pitch, like a well-tuned

musical instrument.

A few historians have tried to identify our Vitruvius as a contemporary, Marcus Vitruvius Mamurra, possibly because Mamurra was also a military engineer and also served under Julius Caesar. Such an identification is highly unlikely since Mamurra is believed to have died around 43-46 BCE. Moreover, Mamurra was known for ostentation and graft. Our Vitruvius claims that he preferred honest poverty:

I have never been eager to make money by my art,” he writes, “but have gone on the principle that slender means and a good reputation are preferable to wealth and disrepute.

An Unlikely Authority

All this makes up the merest outline of a life. And if we look to Roman writers of the era for corroboration, the picture does not become much clearer. Scholars have identified only five Roman writers who mention Vitruvius or his book. These are Pliny the elder, Frontinus, Faventinus, Servius, and Sidonius. As we shall see, how they discuss the man and his work would change as time passed.

Pliny the elder knew De Architectura and listed Vitruvius as a source in his Natural History, but doesn’t mention him by name in the text.

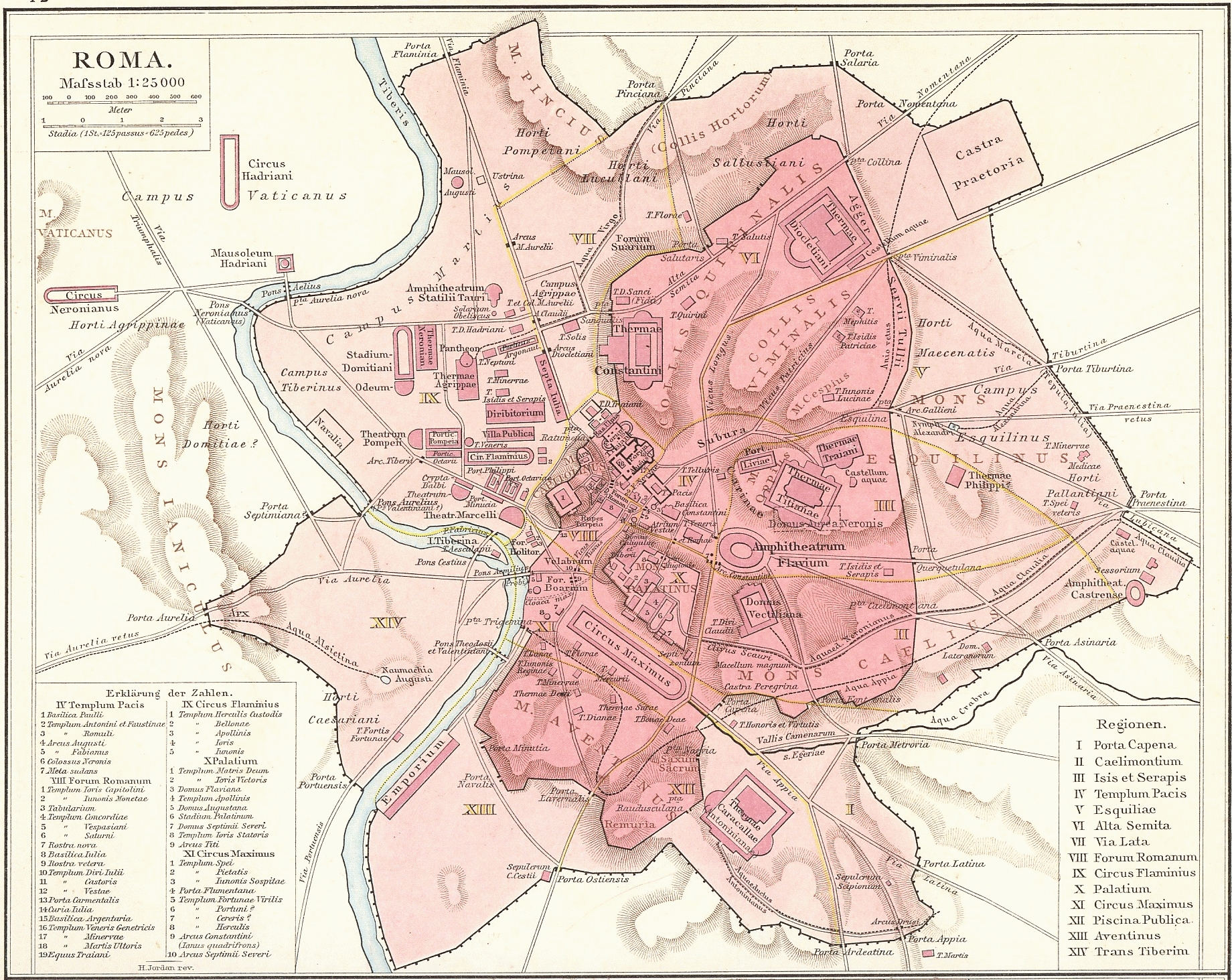

Vitruvius’s name also appears a few decades later in a technical report written by the Roman official Sextus Frontinus. His De Aqueductibus Urbis Romae briefly mentions a Vitruvius who had a supervisory or advisory role in pipe repair or construction. However, Frontinus says nothing more, not even what aqueducts Vitruvius and his pipefitters worked on. De Architectura is not mentioned at all.

A few centuries later, however, the name “Vitruvius” appears to have become culturally significant, shorthand for architectural excellence. We can see this in an abridgement of De Architectura produced by the 3rd-4th century CE architect M. Cetius Faventinus. His De Diversis Fabricis Architectonicae highlights the practical aspects of Vitruvius’s book and leaves out most of the learned theory. By doing this, Faventinus created a handbook on methods and materials for a new audience.

An Illustration from De Architectura. Vitruvius illustrated his theories and rules with technical drawings and examples. Source: idesign.wiki

Vitruvius wrote for the political and philosophical elite. Faventinus seems to have written for supervisors, builders, and contractors. Although this change in audience is significant, even more significant is the fact that Faventinus attributed the work to Vitruvius.

In the world today it is generally held that newer is truer. All else aside, a technical report published in 2019 is considered more reliable than a similar report from 2009. In Classical Rome, the opposite belief held true. Older information was considered more trustworthy because it had stood the test of time.

In attributing the summary to Vitruvius, Faventinus was emphasizing the work’s trustworthiness: it was a handbook from the golden age of Rome. It was not just information; it was Vitruvius’s timeless advice. Copies of Faventinus spread throughout the western empire and were copied by generations of monks for the next thousand years.

Of course it could be argued that Frontinus and Faventinus were builders writing for other builders. Even Pliny was focused on scientific issues. It would not be unusual for such writers to mention Vitruvius or cite his work.

But what, then, are we to make of a literary critic who also cites Vitruvius while discussing poetic diction? In the late 4th century to early 5th century CE, our fourth writer, M. Servius Honoratus, references Vitruvius in his commentaries on Virgil’s Aeneid. In Book VI, Aeneas and his companions arrive at the Cumean Sibyl’s grotto:

Deep in the face of that Euboean crag

A cavern vast is hollowed out amain,

With hundred openings, a hundred mouths,

Whence voices flow, the Sibyl’s answering songs. (Line 43)

Aeneas and the Sibyl in the Underworld. Arnold Houbraken, early 1700s

Discussing Virgil’s poetic diction, Servius cites “Vitruvius the architect” to explain Virgil’s meaning in using such words for access points as aditus and ostia. The commentary would be reasonable only if Servius and his contemporaries believed Vitriuvius was the authoritative answer for any architectural question, whether actual or literary.

An even more lofty status is attributed to Vitruvius at the end of the fifth century CE.

In an ironic letter to a contemporary, the late Roman official and bishop Sidonius Apollinaris rhetorically equates Vitruvius’s mastery of building to Orpheus’s mastery of music, Aesculapius’s mastery of healing, or Euclid’s mastery of geometry (Book IV, chapter 3, 5). In a different letter, he tells his reader that Vitruvius’s book, likely Faventius’s digest, is indispensable for domestic repairs and construction.

Nature as Architect

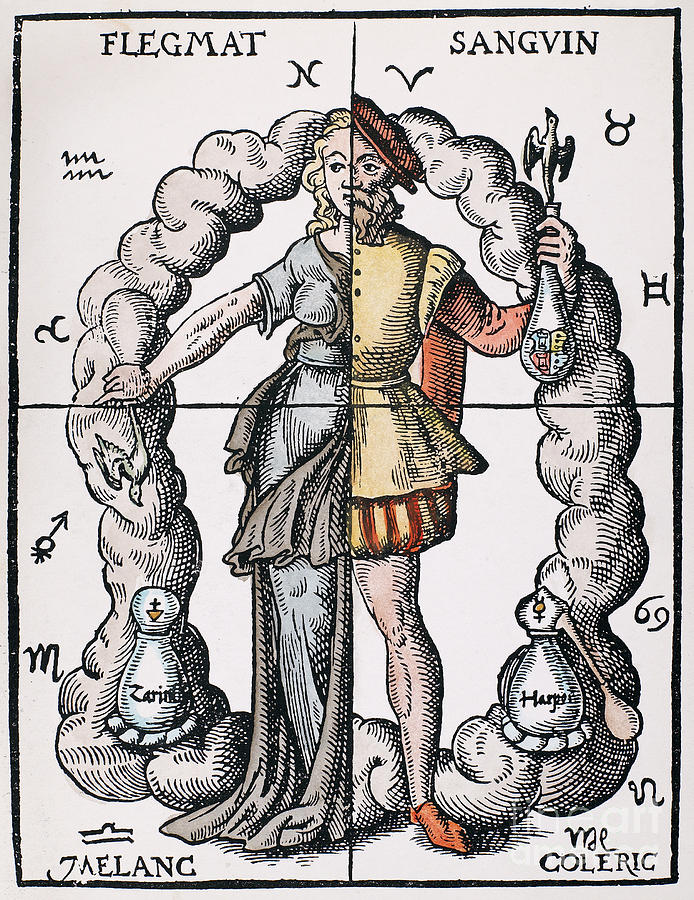

Robert Fludd – The Mirror of the Whole of Nature and the Image of Art.

As historians have suggested, Vitruvius’ status as the leading authority on architecture persisted well into the Italian Renaissance. Whatever else was lost in the collapse of the Roman empire in the west, the concept of Rome as the apex of cultural prestige certainly survived. Likewise, we know that Faventinus’s digest of Vitruvius survived.

Those who aspired to create

monumental works like those of the Roman empire, had much to learn from Vitruvius. Certainly the breadth of learning he demonstrated, along with his hard-won practical know-how appealed to Renaissance thinkers like Leonardo. They considered him one of their own.

Vitruvius’s book is not just about architecture, after all, but about architects and builders as well. What he writes about architects surely appealed to Renaissance architects and engineers—even part-timers like Leonardo. To Vitruvius the architect had a hallowed heritage, stretching back to the framing of the universe:

The heaven revolves steadily round earth and sea on the pivots at the ends of its axis. The architect at these points was the power of Nature, and she put the pivots there, to be, as it were, centres, one of them above the earth and sea at the very top of the firmament and even beyond the stars composing the Great Bear, the other on the opposite side under the earth in the regions of the south. Round these pivots (termed in Greek πόλοι) as centres, like those of a turning lathe, she formed the circles in which the heaven passes on its everlasting way. In the midst thereof, the earth and sea naturally occupy the central point.

Nature itself, according to Vitruvius, is an architect. The architect is, in a certain sense, carrying on and trying to imitate the works of Nature. It is not difficult to imagine why the work in which this passage appears would inspire Leonardo so many centuries later.