Well, the person who demonstrates that there is a god demonstrates this either by means of something clear on its face or by means of something unclear. And there’s no way it can be by something clear on its face; for if what demonstrates that there is a god was clear on its face, then since what is demonstrated is conceived in relation to what does the demonstrating, and for that reason is grasped together with it, as we established, it will also be clear on its face that there is a god—that will be grasped together with what demonstrates it, which is clear on its face. [Note in reference to ‘as we have established’: this can be found in the discussion of demonstration in book II, which I have not included. But the very same point is made about signs at II.125; see n.5 in chapter 4. (The argument is just as fishy here.)]

Written by Nicholaos Jones, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Ancient Greek philosophy begins in Miletus, an illustrious Greek colony along the eastern shore of the Aegean Sea. Before the Milesian philosophers, however, there were the mythic poets. The history of ancient Greek philosophy is, in some sense, a history of breaking with the strategy these poets use to explain why things are they way they are.

Homer (c. 750 BCE) is the best known of the mythic poets. For purposes of comparison with the Milesians, however, Hesiod (c. 700 BCE) is more relevant. Hesiod’s Theogony offers an account for the origin of the gods—from the beginning of the world, through various battles among the gods, to the rise of Zeus and the birth of Zeus’ children. The explanatory strategy is genealogical.

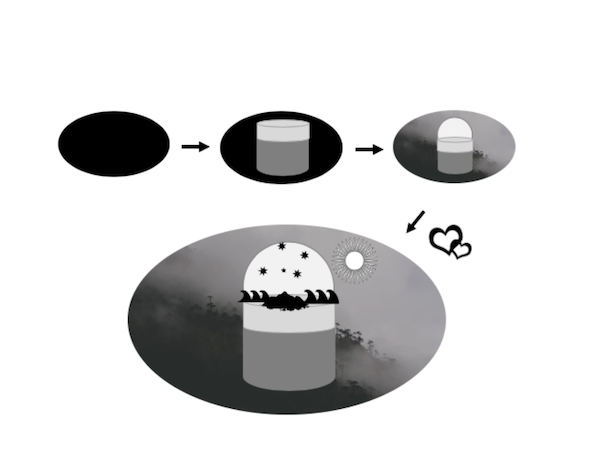

First there is Chasm, a yawning gap or void space.

Earth appears as a flat disk within this gap, and the underworld appears beneath as an enclosed space to contain the roots of what might grow upon the surface. Love appears as well, a procreative force responsible for generating offspring from parents.

Then Chasm and Earth undergo parthenogenesis, reproduction without fertilization. From Chasm come Gloom and Night. From Earth, at first, comes Sky; then, soon after, Hills and Sea. Love’s intervention prompts incestuous union between Chasm and Night, begetting Brightness and Day. Earth and Sky give birth to the encircling Ocean and the brute, uncontrollable titanic forces that shape the land contained therein.

The titans, in time, beget the gods and goddesses. The divinities, in turn, intervene within the realm of mortals, enacting their whimsical and capricious wills.

Hesiod’s account is not scientific, in our sense of scientific. But it is systematic, because each begotten individual has its own powers and its own domain of rule. It is also explanatory; these powers account for phenomena such as earthquakes (Poseidon shaking the earth below the sea) and storms (Zeus hurling thunderbolts).

Hesiod’s account is not scientific, in our sense of scientific. But it is systematic, because each begotten individual has its own powers and its own domain of rule. It is also explanatory; these powers account for phenomena such as earthquakes (Poseidon shaking the earth below the sea) and storms (Zeus hurling thunderbolts).

The history of ancient Greek philosophy is, in some sense, a history of breaking with Hesiod’s explanatory strategy. The first Greek philosopher whose writing we actually have is the Milesian Anaximander (610 BCE – 546 BCE).

Anaximander offers an account of the origins of the world that illustrates a new style of explanation—a philosophical, and perhaps even scientific, style. Unlike Hesiod, Anaximander does not invoke interactions among divine entities. Instead, he restricts himself to interactions among natural processes.

Wood-inlay image representing chaos magnum, the “great gulf” (Luke 16:26), in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Bergamo, Italy. By Giovan Francesco Capoferri, based on a design by Lorenzo Lotto.

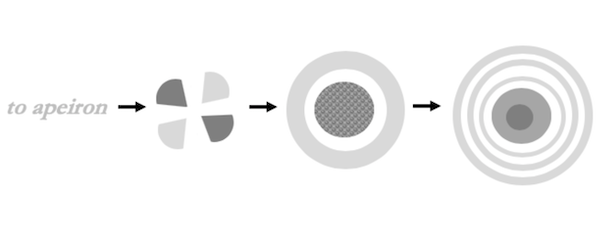

Anaximander calls the original state of the world apeiron. This he defines as a primordial stuff that secretes, or separates out, polarities such as hot and cold. These powers, unlike the primordial stuff, are definite and bounded. Because each one has a definite identity that excludes its contrary, these powers are thereby bounded (or limited) by its opposite. The apeiron, in contrast, excludes nothing and therefore has no definite identity or function.

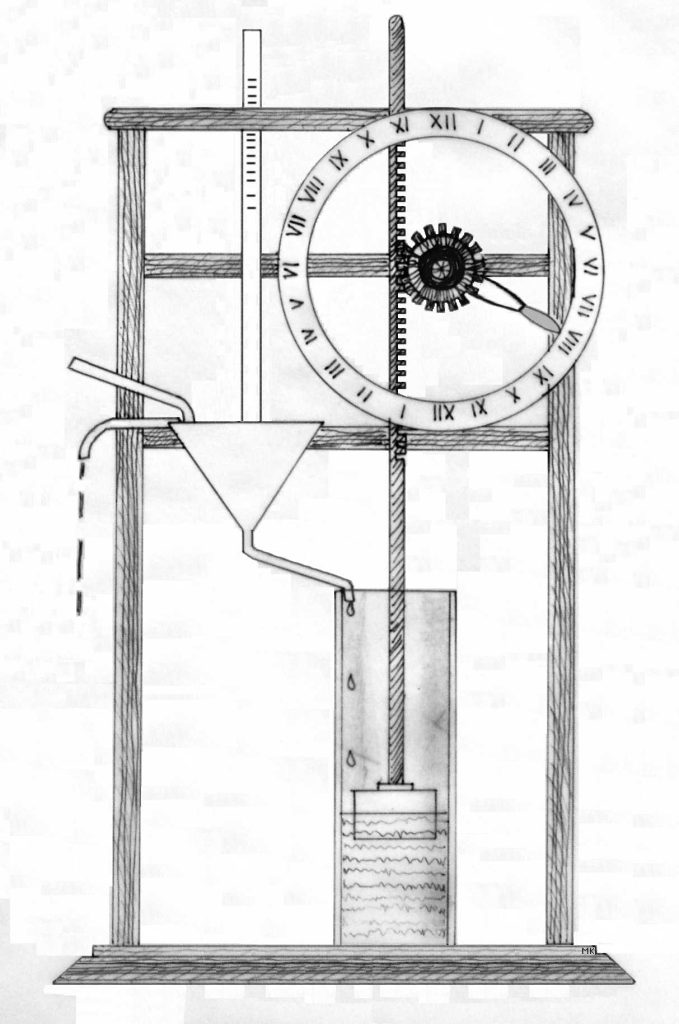

After the apeiron secretes the contraries, it steers (kubernein) them into a structured order—akin to the way a pilot steers a ship in a specific direction, or a leader steers a group into a team. The result is a muddy nucleus surrounded by a layer of air and, further out, a shell of fire. When this structured mass bursts, the fire separates into a series of concentric rings of flame. The outermost ring is the sun; the middle, the moon; the inner rings, stars. Air surrounds the rings, making them mostly invisible. But the air contains holes. Fire from the outermost ring of the sun passes through the largest of these holes, separating the muddy nucleus into earth and sea. The holes also move, and their motion explains the regular appearance and disappearance of the celestial bodies.

Anaximander’s cosmogony retains significant parallels with Hesiod’s. According to Hesiod, creation proceeds from Chasm to Gaia, then onward to opposing powers which beget the separation of the celestial and terrestrial realms, and from there the structures of the earth. Although Anaximander abandons Hesiod’s mythological posits, he retains the general structure of Hesiod’s explanatory sequence, conceptualizing creation as proceeding from the apeiron to the separation of air from earth, onward to rings of fire and their separation into heavenly bodies, and finally to the separation of air from sea.

Anaximander’s cosmogony retains significant parallels with Hesiod’s. According to Hesiod, creation proceeds from Chasm to Gaia, then onward to opposing powers which beget the separation of the celestial and terrestrial realms, and from there the structures of the earth. Although Anaximander abandons Hesiod’s mythological posits, he retains the general structure of Hesiod’s explanatory sequence, conceptualizing creation as proceeding from the apeiron to the separation of air from earth, onward to rings of fire and their separation into heavenly bodies, and finally to the separation of air from sea.

Despite this general similarity, there are significant dissimilarities of detail. For example, according to Hesiod, Chasm is dark, surrounds its creation, and persists within the creation. By contrast, according to Anaximander, the apeiron is none of these. Hesiod also conceptualizes three basic forces—Chasm, Gaia, and Eros. By contrast, Anaximander replaces Chasm with boundless, yet orderly, erotic attraction (Eros).

Moreover, Hesiod presents his account as authoritative because it comes from the Muses. Anaximander’s account, by contrast, derives its authority from the capacity of others to follow his reasoning, to assent or demur from the intelligibility of his conclusions without regard for divine inspiration.

We are prone nowadays to treat scientific inquiry as radically different from mythology. Comparing Hesiod and Anaximander reveals intimations of these differences. Hesiod grounds his inquiries upon private inspiration, and his explanations appeal to divine action. Anaximander, by contrast, grounds his inquiries upon public reason, and his explanations appeal to impersonal forces. Yet comparing Hesiod and Anaximander also reveals that Anaximander’s scientific approach is continuous with Hesiod’s mythological approach. Anaximander’s explanatory concerns closely resemble Hesiod’s, and the structure of Anaximander’s explanations imitates the structure of Hesiod’s. This is, perhaps, some reason for treating scientific inquiry as mythology matured rather than mythology abandoned.