Beware the Ides of March

Written by Ed Whalen, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Too often, students of philosophy are only aware of the great names in ancient Greek philosophy. There are many lesser-known philosophers who developed remarkable arguments that are still relevant today. One of these is the somewhat mysterious figure of Melissus of Samos. Not only was he a great thinker he was also a successful military man who even reportedly defeated the Athenians.

Life of Melissus of Samos

There are few details about the life of Melissus of Samos, but he was believed born on the Aegean Island of Samos about 500 BC. At the time of his birth, Samos was an important naval and trading power. It appears that Melissus was a student of philosophy and was also probably a member of the Samian elite. Sources indicate that he studied under the great Parmenides of Elea, founder of the Eleatic school. Melissus likely traveled to Elea (located in modern-day southern Italy) to study under Parmenides.

At some point he returned to Samos, where he became a military commander and is thought to have become active in local politics. In 440 AD, Samos was an independent state within the Delian League dominated by Athens. The Athenians had effectively turned the Delian League into an extension of their empire. That same year, the Athenians attempted to fully conquer the island. It appears that Melissus, presumably a member of the oligarchic party, was given command of the Samian navy.

He is reported to have inflicted at least one if not two defeats on the Athenians under Pericles. However, Athens ultimately triumphed. Samos was absorbed into the empire and a democratic government imposed on the island. It is not known if Melissus played a part in the failed oligarchic counter-revolution that, with Persian support, tried to oust the Athenians and their democratic allies.

It appears that Melissus also taught philosophy and among his students was the future atomist Leucippus. The date of the Samian philosopher’s death is not known. It appears that he was well-known in his own lifetime.

Philosophy of Melissus of Samos

Melissus wrote a short treatise called On Nature of which extensive fragments have survived. His theories were also referenced in works by other philosophers.

Melissus was regarded as the third member of the Eleatic School, alongside Parmenides and Zeno (best known for his paradoxes). This was a school of Pre-Socratic thought that was established in Elea in the fifth century BC in what is now Veila in southern Italy. Their ontological theory was that everything was one, a theory known as monism. The Eleatics, however, proposed a radical monism in which everything is considered part of a whole, including material, living things. For them, the one is eternal and indivisible. In a significant departure from other pre-Socratic philosophers, the Eleatics valued reason over observation.

By and large, Melissus followed Parmenides and the second great Eleatic, Zeno. Melissus’ philosophy was distinctive in that he believed his predecessors did not fully address the issue of motion or the distinction between being and non-being. Unlike Parmenides, he did not believe that the one was an unchanging present. Melissus held that the one was eternal, that it had always existed and was indestructible. He also argued that it was unlimited, stretching out in all directions and that void, or nothingness, did not exist.

Melissus was a pioneer in applying the deductive method of reasoning. His arguments were very rigorous. At times he seems to suggest that the one is identical with the non-material, referring to it as incorporeal and disembodied.

Influence of Melissus

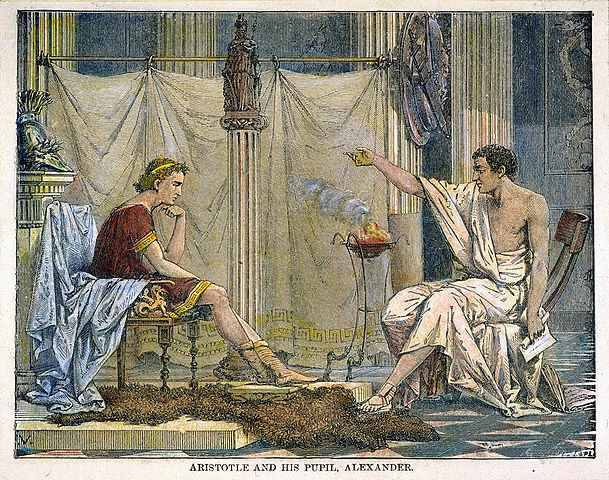

Melissus’ work greatly contributed to the Eleatic School. However, some thinkers, such as Aristotle, ridiculed his claims. If it is true that Melissus taught Leucippus, this suggests he was influential in his own time, especially with the Atomists. The Atomists believed that the world was composed of tiny indivisible atoms and their arguments were clearly influenced by radical monism.

The Sophists were also inspired by Melisuss’ use of deductive reasoning; they used it to prove that nothing existed, as was typical of their nihilism. The Sceptics too were influenced by the deductions of the Samian and his distrust of empirical investigations. They used one of Melissus’ arguments to show that knowledge of the external world was unreliable.

Conclusion

Melisuss of Samos may not be a household name in Greek philosophy, but his contributions were real and substantial. He arguably presented the most logically rigorous version of radical monism. His method of reasoning was also important, influencing the theories of the Atomists, Sophists and Sceptics.

References:

Barnes, Jonathan (1983) The Presocratic Philosophers. New York: Routledge.

Russell, Bertrand (1990) The History of Western Philosophy. London and New York: Routledge

Written by Ed Whalen, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Many ancient societies were deeply influenced by Graeco-Roman Civilization, including early Judaic culture. The exchange between them produced important thinkers in Judaism, among them the philosopher Philo. He is perhaps the most important representative of Hellenistic Judaism whose works had a decisive influence on later Christian thinkers.

The Life of Philo

The exact date of Philo’s birth is not known, but it may have been about 20 BC. He was born into an influential family in Alexandria, Egypt, home at that time to one of the largest Jewish communities in the diaspora. His brother went on to become one of the wealthiest men in the city and even had connections with the imperial family during the reigns of Nero and Claudius.

Philo was brought up in a pious Jewish household and would have studied the Bible and Jewish scholarly works. Alexandria was, at the time, a cultural melting pot of Greeks, Jews and Egyptians. Thus, Philo was deeply influenced by Greek culture and was a student of Hellenic philosophy. He was also a Roman citizen and could speak and read Greek, as was the case with St. Paul, with whom he has some affinities.

Philo was a devoted Jew and visited the Second Temple in Jerusalem at least once in his life. The only event that we know of in any detail is his role in an embassy to the infamous emperor Caligula. Rome’s Prefect in Egypt had ordered the Jews to worship Caligula as god, part of an empire-wide imperial cult. This, of course, was contrary to the strict monotheism of the Jews. The order also came at a time of conflict between the Greeks and the Jews in the city of Alexandria. In 38 AD, many Jews were killed in the city in what was possibly the first-known pogrom.

The Alexandrine Jewish community elected Philo, who was very well-respected, to lead a delegation to Rome and to plead with the Emperor to rescind the Prefect’s orders. Miraculously, Philo was able to persuade Caligula not to force the Jews to worship him or to set up his image in their temples. It is believed that Philo died about 50 AD.

The Theology of Philo

Philo was deeply influenced by Plato and like Plato, he believed that a life of contemplation was superior. The Alexandrine thinker was also influenced by the Stoics, Aristotle and the Cynics. Philo was something of a mystic, believing that a transcendent god could be known by intuition. He also believed that certain numbers, such as seven, had particular religious significance.

Philo believed the purpose of existence was to strive to know god. He held that a supreme being had implanted in humans an innate love of him, allowing humans to achieve a personal union with the divine.

Philo also believed that reason and religion were not incompatible. He used the concept of Logos, or reason, in a new way. It had long been argued that the Logos referred to the rational ordering of the universe. However, Philo argued that Logos, or reason, was begotten of god and was associated with him. In some of Philo’s works Logos is the mediator between the human mind and the divine. He believed that using reason to understand the world also allowed humans to comprehend the transcendent. The Alexandrine thinker also believed that fate could be suspended, allowing miracles to occur. Unfortunately, the philosopher was a poor writer, and his thoughts are often obscure.

Philo and the Bible

Philo was famous for his exegesis, or interpretation, of the Bible. He was very influenced by Greek philosophy—unlike many of his contemporary Jews, Philo did not reject it. He believed that the truths of Plato and the other philosophers were not incompatible with those of the Bible. He found an ingenious way to synthesize Greek thought with the Hebrew Bible, or Torah: allegory. Philo believed that interpreting the Torah and the Bible in an allegorical way allowed the deeper meaning of the texts to be discovered. His commentaries on the Jewish Patriarchs, such as Moses, were also widely read.

Philo’s Influence

Philo was highly respected by the early Christians. His ideas on Logos were especially influential in Christianity; many consider Philo’s works instrumental to the development of the doctrine of the holy spirit, who along with the god the father and son form the trinity in Christian belief. His views on miracles were also influential among Christians.

Philo also wrote an account called De Vita Contemplativa about groups of Egyptian ascetics known as the Therapeutae, whom some believe were Buddhists monks. This work is believed to have greatly influenced the subsequent development of Christian monasticism. Philo’s belief that reason and faith were not incompatible had a profound impact on the development of Christian theology.

While many Jews reject Philo’s allegorical interpretation of the sacred texts, he did influence the Midrash school of Jewish exegesis, which led to the development of a large body of Rabbinic commentaries.

Conclusion

Philo of Alexandria was a man of two worlds who sought to harmonize Judaism and Greek philosophy. This proved very important, even radical. His concepts and ideas greatly influenced early Christianity. Finally, Philo’s ideas on interpretation also had an impact on both Christian and Jewish interpretations of the Bible.

References:

Seland, T. (Ed.). (2014). Reading Philo: A Handbook to Philo of Alexandria. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Written by Ed Whalen, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

We think of Graeco-Roman world as a fairly rational, even secular. However, classical societies were extremely superstitious. In the ancient world, people used religion and magic to help them to cope with what, for them, could be an unpredictable and brutal world.

This led to the rise of not only many religious sects, but also charlatans and impostors.

One of the most notorious of these was Alexander of Abonoteichus. According to one source, he was a false prophet who founded a religion that was enormously influential in the Roman Empire.

Alexander of Abonoteichus

Our main source for Alexander of Abonoteichus is the writer Lucian, a Greek from what is now Syria. However, there are many cultural artifacts, such as coins, that prove that he was a historical figure. Lucian’s account of Alexander is very hostile, and this has colored our perception of him.

Born before 150 ADS in Abonoteichus, a Greek settlement on the Black Sea coast of Asia Minor, Alexander may have been a disciple of the prophet and philosopher Apollonius of Tyana. At some point, he joined a traveling medicine shows that preyed upon the gullible, and during this time he acquired his skills. Alexander was not an ordinary conman—he had ambitions.

The Rise of a Fraud

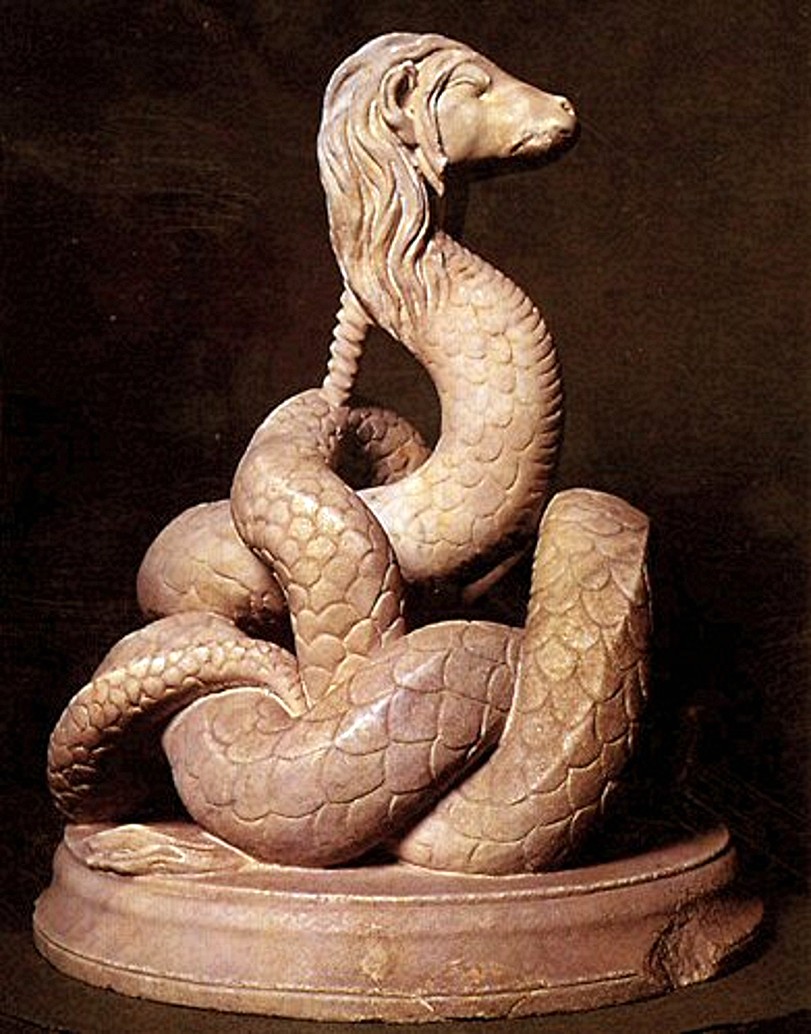

Sometime around 160 AD, Alexander established a snake cult in his home town of Abonoteichus. The sacred snake was worshipped as Glycon, and according to Lucian, it was a hand puppet manipulated by Alexander. Alexander also persuaded the people of Paphlagonians that Glycon was the reincarnation of the god Apollo. Alexander had Glycon prophesying and offering advice on healing. The cult grew enormously popular and attracted many followers from all over the Eastern Mediterranean.

Lucian writes that Glycon would give ‘nocturnal’ oracles and advise, but only to those who paid. One source claimed that the shrine of the snake god provided 80,000 oracles, paid handsomely for each one. Alexander and his circle must have been fabulously rich. Lucian relates that many people asked Glycon questions and often received answers that were nonsensical or irrelevant. Even so, the faithful came in droves.

Many infertile couples would bring gifts to the shrine in the hope that they would become pregnant. Because of the popularity of his cult, Alexander became very influential in Asia Minor, marrying the daughter of the governor.

The Snake God and Roman Emperors

The 160s AD were exceedingly difficult ones for the Roman Empire. It was ravaged by plague and suffered greatly due to wars with German and other tribes. This meant that many people were willing to believe that Glycon channeled the divine. Versified oracles from Glycon were found inscribed on amulets from the 2nd century AD, attesting to the popularity of the cult.

Alexander was personally summoned by Marcus Aurelius in order to provide oracles, and thus went to Rome. The emperor, faced with a major battle with the Germans on the Danuban frontier, asked Glycon how to win. The snake-god (or glove puppet) told Marcus Aurelius that he would win if he sacrificed two lions by drowning them in the Danube. The battle nonetheless was a disaster for the Romans, one of their greatest defeats in the Macromannic War.

However, this does not seem to have ended the influence of the snake-cult in the Roman Empire. Instead, its popularity grew and is credited with the expansion of the town of Abonoteichus, which was renamed Ionapolis.

The End of Alexander of Abonoteichus

The power and respect that Alexander and his cult held in the late 2nd century AD is evidenced by the discovery of coins that depict Glycon.

The cult of Glycon outlived Alexander, and there is evidence that it was still widely practiced in parts of the Aegean a century after his death. Lucian relates that Alexander declared he would live until he was 150, but died about the age of 70 of a terrible disease.

It appears that the glove puppet was abandoned and Glycon was worshipped in an abstract form. There is some evidence that the religion spread to the region around the Danube. There are also indications that Alexander came to be regarded as the son of Asclepius. It is believed the cult of Glycon finally disappeared in the 4th century AD, after the Christianization of the Roman Empire.

Conclusion

Alexander of Abonoteichus was likely a false prophet and a fraud. The cult of Glycon is testament to the search for meaning in a time of crisis. Alexander was able to use a glove puppet to make himself rich and powerful, eventually establishing a religion that lasted centuries.

References:

Lucian (1925). Alexander the False Prophet. Translated by A Harmon.

Written by Ed Whalen, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Athens produced many outstanding individuals, and one of the most remarkable was Cimon. A leading political and military figures of his day, Cimon left an indelible mark on Athens and Greece.

Cimon’s Early Career

Cimon (510-451 BC) was the son of the great Athenian general Miltiades, who had defeated the Persians at Marathon. His mother was a Thracian princess. However, Miltiades fell into disgrace and died. Left the head of his household, Cimon found himself in debt and used his aristocratic connections to pay it off. He then launched a military and political career.

Cimon fought with great distinction at the Battle of Salamis (480 BC) and was elected one of the ten generals of Athens in 479. He was instrumental in the formation of the Delian League, which gave the Athens control over the Greek navy, side-lining the Spartans. He worked closely with the conservative politician Aristides. During his political career, Cimon was associated with the conservatives in Athens.

Cimon’s Victories

While the Persian invasion of Greece failed, the Persians were still a threat. Cimon led several naval expeditions which sought to beat the Persians back in the Eastern Mediterranean. The Athenian expelled Pausanias, a Spartan general suspected of having treasonable dealings with the Persian Emperor Xerxes, from Byzantium. Cimon drove the last of Xerxes’ forces from Thrace. He then attacked a nest of pirates and defeated them on the island of Scyros, which he took for Athens. He became very popular at home and was widely seen as the leader of the conservative party. His main rival was Pericles, the leader of the popular party.

The Pinnacle of Cimon’s Career

In 466, Cimon was operating in the Eastern Mediterranean and commanded a fleet of 200 ships. At this time, the Greek cities in Asia Minor, supported by the Delian League, had thrown off the Persian yoke. A massive Persian army gathered at the mouth of the River Eurymedon in Pamphylia (in modern-day Turkey), aiming to retake the Greek cities in Asia Minor and once more threaten mainland Greece. A bold, aggressive commander, Cimon decided to attack the Persians first. He launched a surprise assault on the Persian ships, destroying their entire fleet. Yet many Persian sailors that landed on the beach joined the Persian forces deployed there. Cimon ordered marines to attack them, inflicting a decisive defeat.

Aftermath of the Battle of River Eurymedon

The battle was a great victory for Cimon, making him the Delian League master of the Eastern Mediterranean. He had beaten back the Persians to such an extent that it was to be nearly twenty years before they menaced the Greeks in the region.

However, Cimon did not press home his advantage. Some believe that he did not want to overextend his forces. It is also likely that many members of the Delian League had become restive, and one the island of Thasos had even revolted. Cimon may have felt unable to conduct any more offensive operations against Xerxes. For two years, he laid siege on Thasos. There were reports that he was bribed by the Macedonian king not to attack his territories, even though many Greeks suspected that he had collaborated with the Persians and had encouraged the Thasians. Pericles and the populists brought corruption charges against Cimon. He was acquitted, but his reputation suffered greatly.

Cimon and Sparta

Like many conservative politicians in Athens, Cimon was sympathetic to Sparta. In 462 AD, Sparta was shaken by a rebellion. The helots, or state-owned slaves, had established a fortress on Mount Ithome. Sparta sought the assistance of Athens and her other Greek allies. Cimon called for the Athenians to intervene on behalf of Sparta. He was granted a force of 4,000 hoplites and they marched on Spartan territories. However, Cimon’s attack on the rebels was a failure. The Spartans became suspicious of the Athens and ordered them to return to Attica. This was a humiliation for Cimon and upon his return to his home city, he was ostracized and eventually exiled.

Cimon’s Later Career

The fall of Cimon transformed Athenian politics. Pericles and his allies were able to seize control of the government and they passed several democratic reforms. They also waged a war against the Spartans in the First Peloponnesian War. Cimon volunteered to fight as a common soldier and many of his followers died bravely in the battle against the Spartans. This convinced many in Athens to rescind his exile. Cimon worked tirelessly to reconcile the two most powerful Hellenic states. In 451, a peace treaty was signed by both sides and this ended the First Peloponnesian War. Cimon may have played a role in this, and indeed was given command of a large fleet at the end of the conflict. Later, Cimon laid siege to the city of Citium in Cyprus, during which he is believed to have died of a wound or illness.

Conclusion

Cimon played a crucial role in the rise to power of Athens and he was one of the architects of the Athenian Empire. He was a great naval commander, driving the Persians out of the Eastern Mediterranean. His pro-Spartan policies made him unpopular in Athens and politically speaking, he was out-maneuvered by Pericles. Cimon wanted Athens to ally with Sparta. If he had succeeded, this would have prevented the cataclysmic Athenian defeat in the Second Peloponnesian War and possibly even the rise of the Kingdom of Macedon.

References:

Holland, Tom (2006). Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. Abacus.

Written by Lydia Serrant, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Plutarch (AD46 – after AD 119) was a Platonic philosopher, essayist, biographer, magistrate, and a priest at the Temple of Apollo later in his life.

Plutarch was known for his involvement in all matters of society, taking on even the humblest of tasks. However, he is best remembered today for Parallel Lives, a series of biographies that followed prestigious Greeks and Romans, and Moralia a collection of essays, letters, and speeches that summarized his life’s work, beliefs, and teachings.

Moralia translated as ‘’Morals’’ or ‘’Matters concerning customs and mores’’ and consists of 78 essays and speeches. From questioning fate to the nature of music, Moralia sheds light on ancient Greek life and offers some of the deepest and most timeless wisdom.

Plutarch’s letter on listening was first delivered as a formal lecture and was later converted into a letter to his young friend Nicander, who was about to embark on the study of Philosophy.

While the letter is written to a youth about to enter a period of intense study, it contains lessons from which we could all benefit.

Plutarch’s descriptions of different kinds of listeners are as relevant today as they were then. The lazy listener, the scornful listener, those who listen with excitement, and the over-confident listener are just a handful of listening types he discusses.

Plutarch’s Listeners

Listening to Lectures (De auditu), in Plutarch, Moralia, Vol. I, Loeb Classical Library No. 197 (1927)

The Selective Listener

Plutarch describes the selective listener as someone who is very good at listening – to what they want to hear.

This refers to the tendency to be most interested in hearing about topics that we find exciting and interesting, and how much easier it is to listen to long speeches from great orators or those we admire.

While most of us are guilty of this – no doubt there is great pleasure in listening to topics that one most enjoys – Plutarch warns that only listening to advice and opinions that are pleasing to the ear may mean we miss other important or useful information. Much good can be hidden away in ‘boring’ lectures or speeches from those we deem less interesting or desirable.

The Disapproving Listener

Most people will have listened to opinions that conflict with our values and meet with our disapproval. While there’s nothing wrong with disagreement, Plutarch encourages us to always keep an open mind. Most importantly, he urges us to listen to the speaker in their entirety first, without judgment.

Judgment or disapproval, Plutarch argues, is in itself a distraction of the mind. Those who attend speeches already in a state of disapproval are distracted, often comparing their own intelligence with that of the speaker, and/or observing others in the audience for signs of admiration and approval. In the process, much information is missed and the listener comes away less informed.

Disapproving listeners are at risk of distorting the information conveyed, rendering the whole experience useless.

Plutarch points out that when we have already decided we are against something, we’re likely to recall only what we consider to be the negative points. Great learning, he says, arises when we ponder and reflect on opinions that are opposite to our own.

The Over-Confident Listener

“In praising a speaker, we must be generous, but in believing his words cautious” – Plutarch

“Don’t believe everything you hear” is an adage as old as time. There are certain speakers we confide in due to their achievements, status or because they have previously given honest and useful advice. In that situation it becomes easier just to believe what you hear without a second thought and leave critical thinking at the door.

Plutarch advises us that no matter how much we admire the speaker, or how dazzling and entertaining the performance is, we must be a ‘heartless critic’ when evaluating the quality of the information we are receiving.

Plutarch did not believe that any speaker should be met with hostility, but warns us to be careful not to be swept away by the current. Just because someone may have useful information the first time, does not automatically qualify them to give good advice the second time. All information should be approached with a clear and critical mind, no matter who says it.

Listening as a Collaborative Process

One of the core lessons from Plutarch’s essay on listening is that the learning process does not solely rely on the speaker or educator. He continuously reminds us that responsibility also rests on the shoulders of the listener. Learning and informing requires the active participation of both parties.

Thus the listener would do well to reflect on the quality of their listening, be mindful of personal flaws, approach all information with caution, and not be afraid to ask questions.

Quality listening does not mean that the listener must be quiet, Plutarch adds. Questions are an important part of the listening process and should always be welcome, so long as they are related to the topic.

Plutarch believed that the major obstacle in learning from others is one’s own shortcomings and insecurities. To remedy this, proper behavior in all educational settings must be observed so that the information can be adequately understood and assessed without the interference of personal preferences.

Whether we tend to drift off during boring lectures or immediately dismiss speakers we dislike, as listeners we are active participants in the cultivation of ideas. Identifying barriers to our listening and learning, especially those we impose upon ourselves, is a crucial part of personal development and self-improvement.

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moralia

https://www.loebclassics.com/view/plutarch-moralia_listening_lectures/1927/pb_LCL197.201.xml

https://www.e-ostadelahi.com/eoe-en/the-art-of-listening/

https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/De_auditu*.html

https://philosophycourse.info/plutarchsite/plutarch-listening.html