Written by Katherine Smyth Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

A Man of Many Names

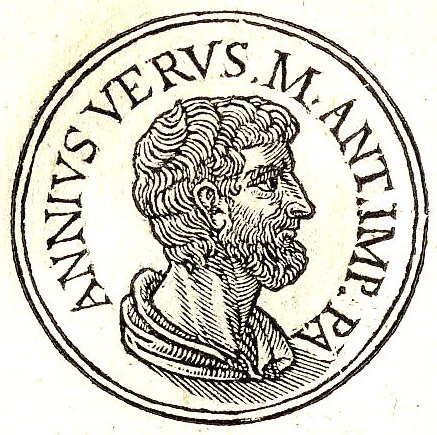

Marcus was born on the 26th of April, in Rome, in the year 121 A.D.. He bore many different versions of his name whilst growing up; these changed as his familial status was altered first by the death of his father, then his unofficial adoption by his grandfather, and finally his legal coming of age. Some of the names he was known by include Marcus Annis Verus, Marcus Annis Catilius Severus, or Marcus Catilius Severus Annius Verus.

But, when Antoninus Pius formally adopted him, as Hadrian’s successor, Marcus became heir to the empire, and his name was changed to Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus Caesar. This name would only change once more; when he became emperor. His final, and full name—Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus—would last until his death.

Roman: Flesh and Blood

Marcus’ family background was as noble as they came. He was of Italo-Hispanic descent on his father’s side and, as such, was a member of the Aurelii, who were based in Roman Spain. The Annia gens is also of Italian descent, with the Annii Veri having risen through the Roman ranks from the 1st century AD. Marcus was related directly to Marcus Annius Verus (I), his great-grandfather, an ex-praetor, and Marcus Annius Verus (II), his grandfather and unofficial adoptive father, who was a patrician.

However, Marcus was also a member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty courtesy of his grandmother, Rupilia. As such, Marcus was also connected directly to Emperors Trajan and Hadrian through Hadrian’s wife Sabina. She was his grandmother’s half sister, with Sabina and Rupilia being daughters of Trajan’s sororal niece, Salonia Matidia.

Domitia Lucilla from “Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum”

Marcus’ mother, Domitia Lucilla, was notable historically, as she was immensely wealthy due to her inherited fortune. As the daughter of a Roman patrician, P. Calvisius Tullus, her wealth was so great that it included brickworks on the outskirts of Rome – which was a boon in an age of rapid expansion – and Horti Domitia Calvillae/Lucillae, the villa on the Caelian hill of Rome, one of the famous Seven Hills of Rome. Marcus would later refer to this villa as ‘My Caelian’, as he was born and raised there, and always remembered it fondly.

Finally, Marcus adopted the gen. name Aurelia when he was chosen as an heir to Antoninus Pius; not just the Emperor, but his adoptive father, and part of the Aurelii Fulvi, who stemmed from the Sabine and were of Italo-Gallic origin. But genes and family names do not an Emperor make. Though Marcus Aurelius was born into noble families, it was his education that would shape the born-leader’s mind and harness his abilities.

Educating an Emperor

Marcus’ formal education was instilled through several private tutors as befits his aristocratic standing; his adoptive father, Marcus Annius Verus (II), through patria potestas authority when Marcus Annius Verus (III) died around 124, oversaw his grandson’s upbringing. Marcus’ education taught him to be of good character and to avoid bad temper, something he recognized as being of great value, and he thanked his grandfather for his wisdom.

“From my grandfather Verus I learned to relish the beauty of manners, and to restrain all anger.” Meditations, I.1

Diogenetus, a painting master, also had great impact on Marcus; as it appears it is he who introduced the young man to philosophy and a philosophic way of life. This extended to Marcus taking up the robes and habits of a philosopher in the year 132. This involved wearing a rough Greek cloak whilst studying, and he would sleep on the ground for a period, although the latter part he would give away after a time, due to the many frequent and vocal concerns of his mother.

Marcus Annius Verus from “Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum”

Amongst his other tutors were the Homeric teachers Alexander of Cotiaeum, Trosius Aper, and Tuticius Proculus, all who taught him Latin, with Marcus thanking Alexander for teaching him literary styling,

which can be seen in Marcus’ Meditations. From AD 136, Marcus had three Greek tutors, Aninus Macer, Caninius Celer, and Herodes Atticus, along with Marcus Cornelius Fronto for Latin.

Late in 136 Marcus’ life changed dramatically; he took the

toga virilis and began his training in oratory. After nearly dying, Emperor Hadrian, whilst convalescent in Tivoli, chose Marcus’ intended father-in-law,

Lucius Ceionius Commodus, as his successor. Lucius took the name Lucius Aelius Caesar, making Marcus as Lucius’ adoptive son, a direct successor to the throne.

However, Lucius did not live long enough for this to happen; Instead, Lucius died the night before delivering his speech to the senate, in 138. Hadrian then selected a new heir; Aurelius Antoninus, the husband of Marcus’ aunt, Faustina the Elder. In a bold move, and as part of the terms of this agreement between Hadrian and Antoninus, Antoninus was to adopt Marcus and Lucius’ son Lucius Verus. This once again implied that Emperor Hadrian had always kept Marcus in mind for the role of Emperor, eventually.

Upon the death of Hadrian, Antoninus was made Emperor, and Marcus’ previous betrothal was annulled; Marcus would instead marry

Antoninus’ daughter, Faustina the Younger. In 140 Marcus was made consul, he was then appointed as a

seviri and became the head of the equestrian order with the title

princeps iuventutis. As the heir apparent to the Empire, he also took the name Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus Caesar; a title he would remind himself not to take too seriously with the following admonition:

“Take care that thou art not made into a Caesar, that thou art not dyed with this dye; for such things happen. Keep thyself then simple, good, pure, serious, free from affectation, a friend of justice, a worshipper of the gods, kind, affectionate, strenuous in all proper acts. Strive to continue to be such as philosophy wished to make thee. Reverence the gods, and help men. Short is life. There is only one fruit of this earthly life, a pious disposition and social acts. Do everything as a disciple of Antoninus.” Meditations, VI.30

Faustina the Younger (130–175 AD). Marble, ca. 161 AD. From the area of Tivoli.

Life and service under Antoninus saw Marcus rise through the ranks, and at the senate’s request he joined all the priestly colleges, although there is only direct evidence of him joining the Arval Brethren. Despite Marcus’s objections, he was also required to adopt the habits of his position, the aulicum fastigium or ‘pomp of the court’. As such, he was also made to relocate his home to the House of Tiberius, the imperial palace on the Palatine, something he was loathed to do and which caused him some sadness.

The trappings of his position did not sit well with his philosopher’s mind, and he would struggle to reconcile the two for the remainder or his life. However, through the words ‘Where life is possible, then it is possible to live the right life; life is possible in a palace, so it is possible to live the right life in a palace’, he was convinced the two could work together.

As quaestor, and under the tutelage of Fronto, Marcus received training for ruling the state. He gained practice by dictating dozens of letters, receiving oratory training giving speeches to the senators, and being educated in matters of State. In 145 he was made consul for the second time, with Fronto urging him to rest well before his appointment as Marcus had complained of an illness previously. This ongoing illness would haunt him for many years, especially as he had never been particularly healthy or strong.

Around 146-147, Marcus’s health took a downward turn, historically it is unclear if this was physical, mental, or a combination of both, as he drifted away from his studies in jurisprudence, and he tired from his exercises in imaginary debates. At this point, Marcus’ formal education was ended, and his philosophic tendencies began to return to the fore.

Titlepage of an 1811 edition of Meditations by Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, translated by R. Graves.

Fronto had warned Marcus against philosophical studies, as he disdained both philosophy and philosophers. He had contempt for Marcus’ sessions with Apollonius of Chalcedon,

as it is probably he who introduced Marcus to Stoicism. Fronto’s attitude would lead to a distance growing between master and student that would never be bridged. Marcus would keep in touch with Fronto, but from here on he chose to ignore Fronto’s opinions.

Domestic Joys and Heartbreak

In April of 145, Marcus and Faustina finally married, having been betrothed since 138. During their marriage they would have at least 14 children over a 23-year period; including two sets of twins, and only one son and four daughters outliving their parents. The first child, Domitia Faustina, was born in 147, and the next day Marcus received tribunician power and the imperium from Emperor Antoninus.

Although many of his children would not live past early childhood, Marcus’ joy at each birth was celebrated with the minting of Imperial coins, many of which can be seen in museums today. Sadly, this period also marked the deaths of his beloved mother, Domitia Lucilla, and Cornificia, his sister. This period of emotional upheaval may have contributed to Marcus’ downward spiralling health, and cemented his Stoic beliefs: that Nature will always rule men.

Rise to Power

At this time, Lucius Verus began his political career, first as consul in 154, and again in 161, this time with Marcus. Antoninus turned 70 in AD 156, and had grown physically weak; needing stays to keep him upright and nibbling dried bread to stay awake through morning receptions. During this time, Marcus took on more and more administrative duties, including those of praetorian prefect when Gavius Maximus died in 156 or 157. Marcus and Lucius were both designated as joint consuls for the coming year in 160, as Antoninus was quite ill by this time.

Statue of Antoninus Pius, Palazzo Altemps, Rome

On 7th March, 161, Emperor Antoninus Pius died at his ancestral estate of Lorium, in Eturia. Having summoned the imperial council, and having handed over the state and his daughter to Marcus, as evening fell and the night-watch came to ask the password, he uttered it before turning over as if to sleep – aequanimitas (equanimity). So ended the rule of Anotnius Pius and began that of Marcus Aurelius.