The Course of Empire: Destruction, Thomas Cole (1836).

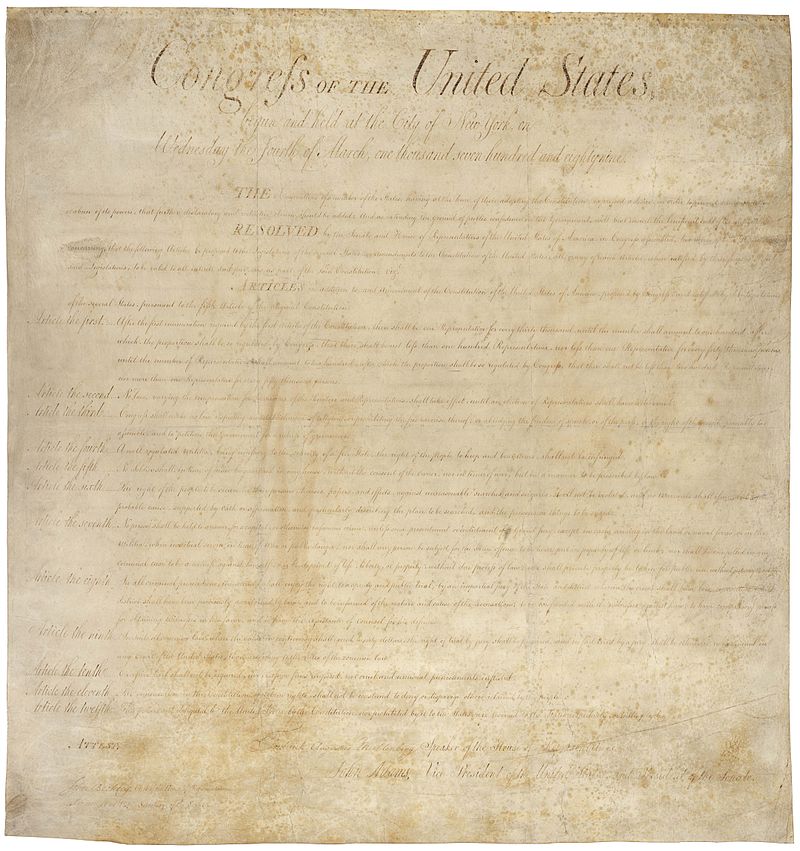

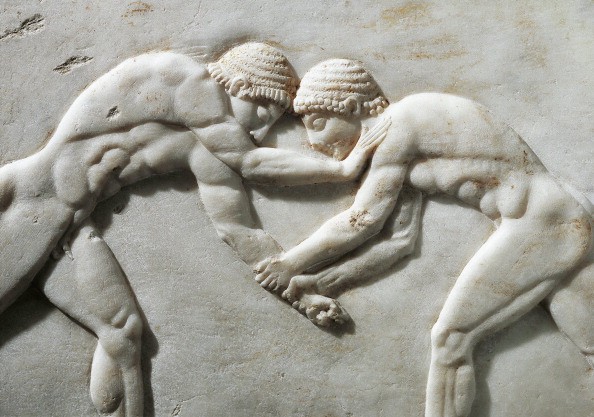

Page one of the original copy of the Constitution.

Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States, by Howard Chandler Christy (1940).

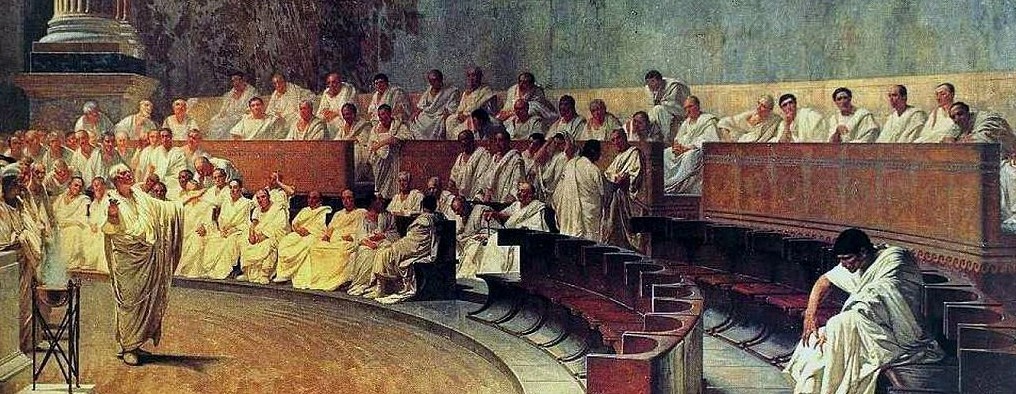

“Leave America divided into thirteen or, if you please, into three or four independent governments—what armies could they raise and pay—what fleets could they ever hope to have? If one was attacked, would the others fly to its succor, and spend their blood and money in its defense? Would there be no danger of their being flattered into neutrality by its specious promises, or seduced by a too great fondness for peace to decline hazarding their tranquillity and present safety for the sake of neighbors, of whom perhaps they have been jealous, and whose importance they are content to see diminished? Although such conduct would not be wise, it would, nevertheless, be natural. The history of the states of Greece, and of other countries, abounds with such instances, and it is not improbable that what has so often happened would, under similar circumstances, happen again.” – Federalist No. 4“A FIRM Union will be of the utmost moment to the peace and liberty of the States, as a barrier against domestic faction and insurrection. It is impossible to read the history of the petty republics of Greece and Italy without feeling sensations of horror and disgust at the distractions with which they were continually agitated, and at the rapid succession of revolutions by which they were kept in a state of perpetual vibration between the extremes of tyranny and anarchy.” – Federalist No. 9“Had Greece, says a judicious observer on her fate, been united by a stricter confederation, and persevered in her union, she would never have worn the chains of Macedon; and might have proved a barrier to the vast projects of Rome.” – Federalist No. 18

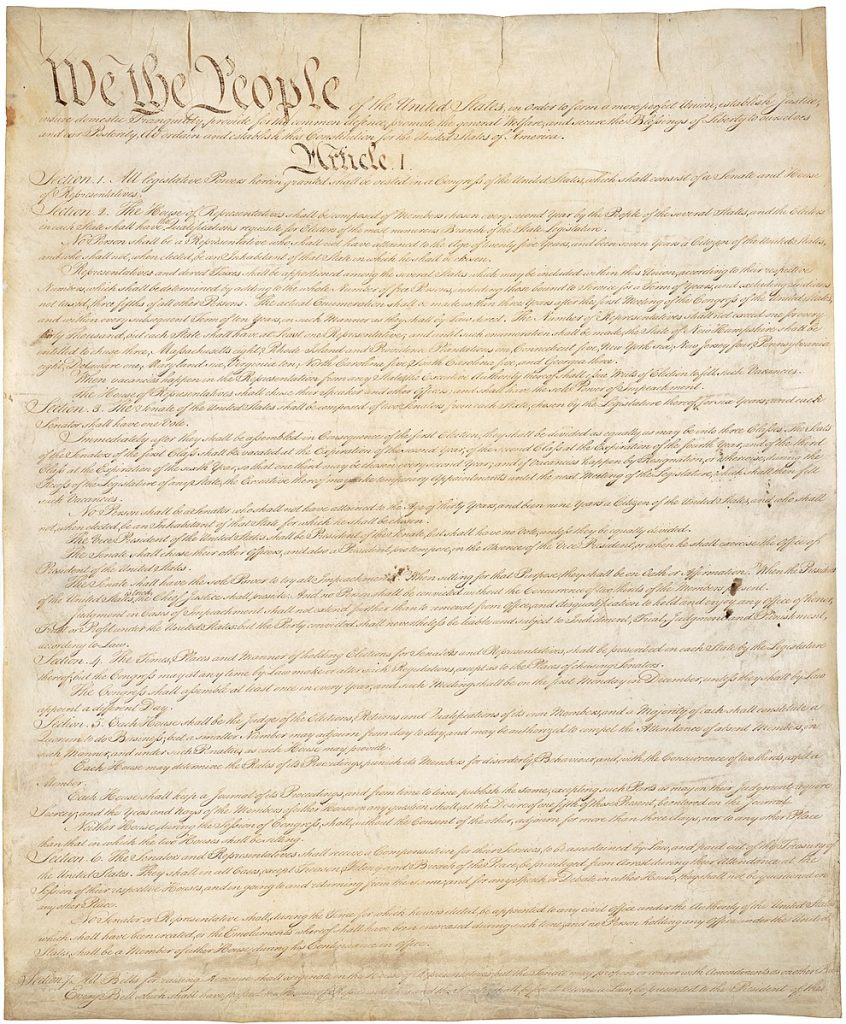

From left to right: John Jay, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton

“In large republics, the public good is sacrificed to a thousand views, in a small one, the interest of the public is easily perceived, better understood, and more within the reach of every citizen; abuses have a less extent, and of course are less protected…. the duration of the republic of Sparta was owing to its having continued with the same extent of territory after all its wars; and that the ambition of Athens and Lacedaemon to command and direct the union, lost them their liberties, and gave them a monarchy.” – Antifederalist No. 14“All human authority, however organized, must have confined limits, or insolence and oppression will prove the offspring of its grandeur, and the difficulty or rather impossibility of escape prevents resistance. Gibbon relates that some Roman Knights who had offended government in Rome were taken up in Asia, in a very few days after. It was the extensive territory of the Roman republic that produced a Sylla, a Marius, a Caligula, a Nero, and an Elagabalus. In small independent States contiguous to each other, the people run away and leave despotism to reek its vengeance on itself; and thus it is that moderation becomes with them, the law of self-preservation.” – Antifederalist No. 3“Where the people are free there can be no great contrast or distinction among honest citizens in or out of office. In proportion as the people lose their freedom, every gradation of distinction, between the Governors and governed obtains, until the former become masters, and the latter become slaves. In all governments virtue will command reverence. The divine Cato knew every Roman citizen by name, and never assumed any preeminence; yet Cato found, and his memory will find, respect and reverence in the bosoms of mankind, until this world returns into that nothing, from whence Omnipotence called it. That the people are not at present disposed for, and are actually incapable of, governments of simplicity and equal rights, I can no longer doubt. But whose fault is it? We make them bad, by bad governments, and then abuse and despise them for being so.” – Antifederalist No. 3

Three of the Anti-Federalists.

“Men have differed in opinion, and been divided into parties by these opinions, from the first origin of societies; and in all governments where they have been permitted freely to think and to speak. The same political parties which now agitate the US. have existed thro’ all time. Whether the power of the people, or that of the ἄριςτοι [ancient greek for “aristocracy” or “nobility”] should prevail, were questions which kept the states of Greece and Rome in eternal convulsions; as they now schismatize every people whose minds and mouths are not shut up by the gag of a despot. And in fact the terms of whig and tory belong to natural, as well as to civil history. They denote the temper and constitution of mind of different individuals.” – Jefferson to John Adams, June 27th, 1813“Men by their constitutions are naturally divided into two parties. 1. Those who fear and distrust the people, and wish to draw all powers from them into the hands of the higher classes. 2dly Those who identify themselves with the people, have confidence in them cherish and consider them as the most honest & safe, altho’ not the most wise depository of the public interests. In every country these two parties exist, and in every one where they are free to think, speak, and write, they will declare themselves. Call them therefore liberals and serviles, Jacobins and Ultras, whigs and tories, republicans and federalists, aristocrats and democrats or by whatever name you please; they are the same parties still and pursue the same object. The last appellation of aristocrats and democrats is the true one expressing the essence of all.” – Jefferson to Henry Lee, August 10th, 1824

Statue of Thomas Jefferson at the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C.

“Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.” – Federalist No. 55

“Sometimes it is said that man can not be trusted with the government of himself. Can he, then, be trusted with the government of others? Or have we found angels in the forms of kings to govern him?” – Jefferson’s First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1801

Jefferson (left) and Hamilton (right).

“For ourselves, let the annual return of this day forever refresh our recollections of these rights and an undiminished devotion to them.”